Brenda Cromb

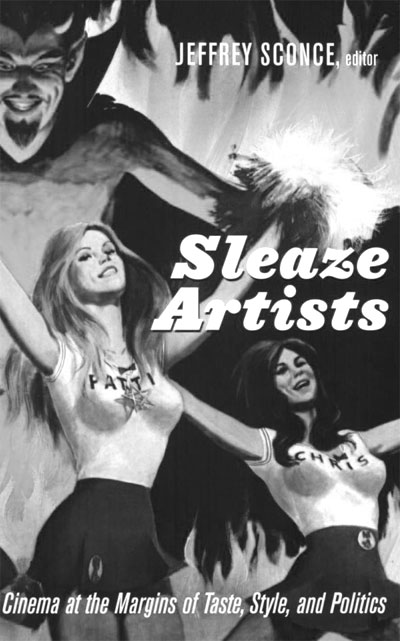

Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Politics. Edited by Jeffrey Sconce. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007, 352 pp.

Being one of the jaded cinephiles Sconce describes in his introduction, looking to bad films for “that shock of recoginition, a random moment of poetic perversity, the epiphany of the unexpected,” (9) I dove into Sleaze Artists, eager to find more facets of sleaze to celebrate. Rather than a series of explanations of the subversive possibilities of violence or the sheer aesthetic experience of sexploitation, I found a range of approaches dominated by ambivalence rather than celebration, demonstrating the versatility of ‘sleaze studies’. Sconce divides the collection into two parts: one that considers the films in their historical contexts, and one that looks at how cult followings have carried the films into contemporary film culture. The effect is a shift from the specific to the general, beginning with detailed discussions of films, like Colin Gunckel’s examination of Aztec horror and Mexican national identity, as well as Kevin Heffernan’s reception history of Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1973), and moving to broader deliberations of film and taste culture, with Greg Taylor’s “Pure Quidditas or Geek Chic? Cultism as Discernment.”

Being one of the jaded cinephiles Sconce describes in his introduction, looking to bad films for “that shock of recoginition, a random moment of poetic perversity, the epiphany of the unexpected,” (9) I dove into Sleaze Artists, eager to find more facets of sleaze to celebrate. Rather than a series of explanations of the subversive possibilities of violence or the sheer aesthetic experience of sexploitation, I found a range of approaches dominated by ambivalence rather than celebration, demonstrating the versatility of ‘sleaze studies’. Sconce divides the collection into two parts: one that considers the films in their historical contexts, and one that looks at how cult followings have carried the films into contemporary film culture. The effect is a shift from the specific to the general, beginning with detailed discussions of films, like Colin Gunckel’s examination of Aztec horror and Mexican national identity, as well as Kevin Heffernan’s reception history of Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1973), and moving to broader deliberations of film and taste culture, with Greg Taylor’s “Pure Quidditas or Geek Chic? Cultism as Discernment.”

This is not to say that the ‘historical’ section does not provide new insight. Chuck Kleinhans offers a consideration of the cynical voice of ‘authority’-more prurient than educational-in sleaze documentaries on sex. Concluding finally that these reflect the commodification of knowledge about sex, he asserts that “these sleazy documentaries present an inversion of art’s aspiration to the sublime and become instead examples of the capitalist grotesque” (116). Another standout is Tania Modleski’s consideration of sleaze auteur Doris Wishman, in which she contends that Wishman’s work, though admittedly as violent, exploitative and misogynist as any of her male peers’, may still be read as having feminist possibilities. Modleski’s piece, written years earlier, reflects her ambivalence, even as she argues that feminists’ insistence on their right to politically incorrect fantasy and behavior has to be seen […] in light of the repression historically imposed upon them” (69).

The second half of the book takes more sweeping approaches. Chris Fujiwara’s intriguing “Boredom, Spasmo, and the Italian System,” suggests looking at boredom, the exact opposite of sleaze’s promise, as “a path for research” (245). Also worthy of note is Kay Dickinson’s study of the disjunctive soundtracks used in ‘video nasties’. Dickinson examines the role of synthesizer music in creating the unsettling power of the Italian horror films banned on video in the United Kingdom.

Though I have only been able to briefly highlight a few standouts, that should not be read as a disendorsement of the rest of the book’s essays, from Eric Shaefer’s consideration of how sexploitation advertising framed audiences (which provides excellent coverage of the industry) to Harry M. Benshoff’s take on films about homosexuality in the pre-Stonewall military. The collection is worth picking up if only for Sconce’s closing essay, “Movies: A Century of Failure,” which points out film criticism’s legacy of disparaging films that fail to live up to the ‘true artistic potential’ early critics saw in the medium. In ‘cine-cynics’ who delight in the Giglis that expose Hollywood product as anything but art, Sconce sees viewers who recognize film for what he, somewhat depressingly, concludes it really is. “Camp,” he argues, “has always been its own form of deconstructive critical theory and thus remains a crucial tool to help us redouble our Adornoesque vigilance against our own impending mass stupidity and worseness. If the cinema is to be ‘saved’, it will be by finally and forever reframing it as practice” (306). While hardly the unequivocal celebration of trash promised by the Satan’s Cheerleaders image on the cover, Sconce’s collection did give me pause to reconsider my own cheerful embrace of sleaze. The broad range of approaches applied here, allow for sleaze to mean more than one thing-and, taken together, provide insight into how sleaze cinema can be submitted to academic scrutiny, and how bad films will continue to haunt our definitions of film as art.