Colleen Montgomery

‘The economy’ is, after all: a thicket of information about jobs and real estate and banking and investment. But the tools of economics can be just as easily applied to subjects that are more— well, more interesting.

– Levitt and Dubner, Freakonomics (13)

Whether conceived as art, propaganda, or entertainment for the masses, cinema has held a central position in Russian culture and society for over a century. Lenin’s famous declaration that, “of all the arts, the most important for us is cinema”[1] has long been reflected in the Russian/Soviet state’s ideological and financial investment in the cinema. So too has it been evidenced by Russian audience attendance levels, which, up until the 1990s, consistently remained among the highest in the world per capita. In the early 1990s, however, a series of cultural and economic changes resulting from the dissolution of the Soviet Union led to an unprecedented period of decline for the Russian film industry. In spite of this, many prominent critics and filmmakers faulted a ‘weak cinema mythology’ for the dwindling state of their national film industry, and called for filmmakers to create a new national mythology to lift the spirits of the Russian people and reinstate the cultural and economic weight Russian cinema once held on a national and international level. In 1992, Daniil Dondurei, chief editor of the foremost Russian film journal Iskusstvo kino, called for Russian filmmakers to “create a new national hero” instead of “wasting time on films […] that simply reopen wounds.” In 1998, during his address to the Russian Filmmakers’ Union Congress, acclaimed Russian director Nikita Mikhalkov[2] advocated the “creation of a positive film hero” to help restore Russian cinema to its former glory (qtd. in Hashamova 296). Numerous Russian filmmakers, including Mikhalkov himself with his ‘heritage films’ Burnt By The Sun (1996) and The Barber of Siberia (1999), as well as Alexander Sokurov, with his groundbreaking epic Russian Ark (2002), heeded this call in fashioning new, positive national myths and heroes that “idealize Russia’s imperial past and culture” (Hashamova 296). Alexei Balabanov’s post-Soviet films, on the other hand, with their macabre forays into the realms of pornography, exploitation, criminality and the Russian mafia, carve out a markedly alternative mode of post-Soviet cinema. Rather than offer a nostalgic view of Russian history and culture, his films-furnished with a host of ‘freakish’ and unsavoury characters far from the kind of ‘heroes’ Dondurei and Mikhalkov envisioned-cast a bleak light on Russia’s imperial past and propose no new national mythologies for the future.

In the first post-Soviet decade, Russian filmmakers “watched their domestic audience, their international renown, and their cultural authority shrink and all but disappear” (Larsen 491). In 1991, the almost overnight dissolution of the Soviet nation-state-which once occupied one sixth of the earth’s surface-into fifteen independent states had devastating effects on the Russian economy and many of the country’s national industries. The transition from communism and state-ownership of resources, to democracy and a free market economy, had particularly catastrophic consequences for Russia’s film business. National, centralized systems of production and distribution disappeared and state subsidies-on which the industry had always relied to finance and distribute films-were all but eradicated, sending Russian cinema into a period of unprecedented crisis. Further driving down ticket sales (particularly for Russian films) to an all-time low were: the deterioration of state-run studios and distribution systems, outdated and poorly equipped Soviet-era cinemas, growing television and video markets, widespread video piracy, and a rapid, unchecked influx of American films into Russian theatres.[3]

While there was a brief but intense boom in production between 1991 and 1992, during which time three hundred films were produced,[4] domestic attendance levels and returns on Russian films remained at record lows. In fact, Russian films accounted for just three to eight percent of total box office revenues for the decade and it is estimated that, on average, Russians purchased less than one film ticket per year in the 1990s (Lawton 98-102). While Dondurei and Mikhalkov sought to rescue Russian cinema from this state of near-ruin by crafting films that celebrate and glorify Russian history and aim to promote nationalist pride, Alexei Balabanov’s films offer a radical alternative to this form of post-Soviet heritage film. Looking at two of his most widely distributed, yet very stylistically divergent films, Of Freaks and Men (1998) and Dead Man’s Bluff (2005), I will discuss how Balbanov’s post-Soviet films: deconstruct long-held national mythologies, particularly those relating to the history of Russian cinema; create a new type of anti hero-a ruthlessly capitalist, deeply individualist figure lacking any overarching moral code or ethical imperative; and, lastly, shed light on the socio-economic impact of the introduction of a Western capitalist system to post-Soviet Russia.

‘Heritage Porn’: Re-visioning Russian Film History

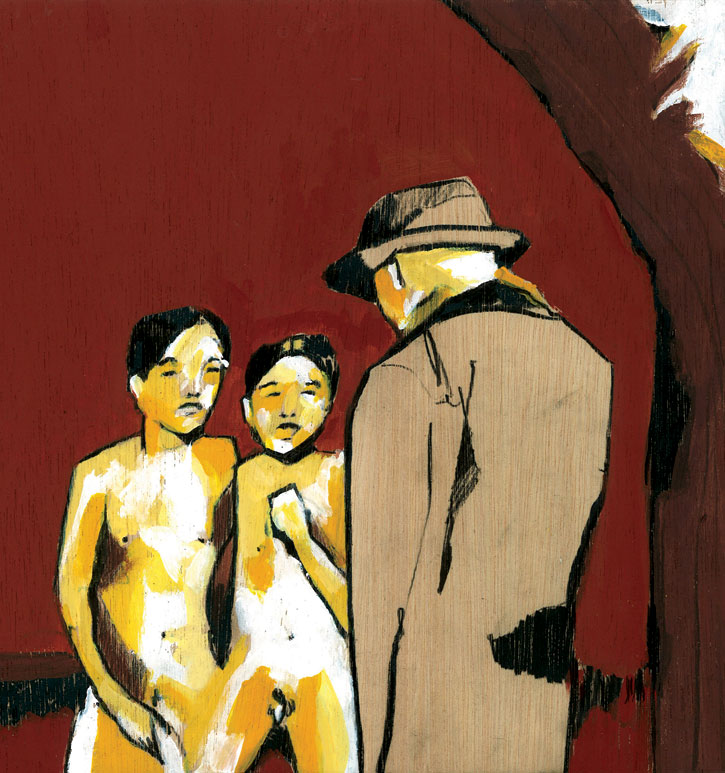

From Eisenstein to Vertov, Pudovkin and Tarkovsky, Russian filmmakers have long held a prominent place in the canon of global film history and film theory. This ‘most important of all the arts’ has also been a central part of Russia’s national mythology since the medium’s very inception. However, amid the political and economic uncertainty ushered in by the demise of the Soviet state, the soundness of such national ideologies and mythologies was called into question. Free of the strictures of Soviet state-regulated censorship that once greatly limited any such questioning, many writers, artists and directors of the post-Soviet era, including Balabanov, began to openly interrogate and deconstruct these mythologies. As Balabanov stated, “I am part of the first generation not limited by censorship. When I started making films, it was possible to do anything you wanted” (Guardian 12). Of Freaks and Men, which one critic labelled “heritage porn” (Clarke 16), is exemplary of Balabanov’s perverse revision and questioning of the official (and esteemed) history of Russian cinema. Set in St. Petersburg in the late 1890s, the film is centred on a gangster-turned-pornographer, Johann (Sergei Makovetski), and his sordid relations with the people who buy, produce and participate in his fetish photographs (and later, films), which depict young girls being spanked by an older ‘nanny’. With its monochrome stock and use of intertitles, the film is artfully crafted to replicate and pay homage to the visual style of turn-of-the-century films. Simultaneously, however, it presents an unofficial, alternate history of Russian cinema: one of pornography, and mafia bosses-turned-directors, rather than one of technical innovation and revolution, of pioneering theorists and auteurs. Thus, in this sepia-toned tale of flagellation, exploitation and murder, Balabanov effectively strips away the sheen of grandeur with which official film history has, for so long, endowed Russian cinema, and instead explores (quite literally speaking) its fleshy underbelly.

Balabanov articulates this revision of Russian film history, first and foremost, via the character of the filmmaker/cinematographer, Putilov (Vadim Prokhorov). Far from being a visionary artist or intellectual, Putilov is neither ‘kinoeye’, nor ‘kinofist’, but simply ‘kinoteen’. Though he is admittedly fascinated with his recently acquired movie camera and the prospect of capturing, for the first time, ‘moving pictures’, Putilov not only has no political or artistic mandate, but no real say at all over the films that he makes. He simply captures what is put in front of him to record, partly out of sheer fear of his gangster boss, Johann. Johann himself, arguably both the creative director and executive producer of the flagellation films, is equally far from attaining ‘auteur status’. He is a ruthless businessman looking to profit, at any cost, from the soft-core pornographic images he creates and circulates throughout St. Petersburg with the help of his henchman Viktor Ivanovich (Viktor Sukhorukov). Composition, framing, lighting, narrative, and more generally, the artistry of filmmaking as a whole, seem to be of no concern to Johann. His is a cinema of a sole attraction: sexual titillation. The portrayal of these two men, the first a bewildered teen and the second a mob boss bereft of any artistic vision, points to Balabanov’s own scepticism as to the illustrious reputation of Classical Russian cinema. He not only calls into question the cultural elevation of the Classical Russian auteur; he willfully deconstructs the image of Russian filmmaking as a revered and respected art.

Post-Soviet Freakonomics

While set in 1890s Russia, Of Freaks and Men expresses economic concerns very much rooted in the film’s 1990s post-Soviet context. Surveying the socio-economic landscape of post-Soviet Russia, Anuradha Chenoy argues that, as the collapse of the collective system gave way to privatization, ownership of some 100,000 state-owned enterprises throughout the former Soviet Union was transferred to an emergent “new class of individual entrepreneurs” (190). Although there is no state-imposed economic reform in the late 19th century world of Of Freaks and Men, a similar transfer or shift of ownership and economic power drives the film’s narrative progression. At the film’s outset, the representatives of the Russian bourgeoisie, the Chekhovian patriarchs, Engineer Radlov (Igor Shibanov) and Doctor Stasov (Aleksandr Mezentsev), possess the greatest social and economic agency. The members of the Russian underclass, the Radlovs’ maid, Dariya (Tatyana Polonskaya), the Stasovs’ maid, Grunia (Daria Lesnikova), Grunia’s brother, Johann, and his second in command, Viktor Ivanovich, all serve the traditional heads of household in some form-making deliveries, fashioning portraits and cleaning house. As the film progresses, however, just as the pornographic pictures infiltrate and disturb the quiet order of the Radlov and Stasov homes, so does the underclass gradually penetrate and seize control of these bourgeois spaces, assuming all the socio-economic clout of the previous inhabitants. It is not by accident that it is Johann, the character who has recently returned from an extended period of time living in the West, who initiates this overturning and restructuring of the hierarchy of power. Johann provides the startup capital (also a central motif in Dead Man’s Bluff), which he acquired in the West, that sets the wheels of the pornography industry-and thus the central conflicts of the narrative-in motion.

Moreover, Johann’s Western capital is arguably representative of the rapid “shock therapy”[5] introduction of Western capitalist economics to the post-Soviet states and the ensuing social transformations it instigated. As Aslund and Olcott note, the transition to a free market economy in the 1990s brought about massive shifts in the balance of power in Russian society. New classes gained control of government and industry, while “beggars and homeless persons [became] frequent sights in the cities, many [coming] from the old Soviet white-collar” (xv). Members of the intelligentsia (specialists, scientists, professors, etc.) were among those most deeply affected by these changes, as cuts in state subsidies drove wages down to unparalleled lows and unemployment levels up to record highs. According to Chossudovsky, between 1992 and 1993, the average university professor in Russia earned just eight dollars a month, and the average nurse working in a Russian urban clinic, just six dollars a month (227).[6] Of Freaks and Men mirrors this economic upheaval as characters representative of the intelligentsia, Doctor Radlov and Engineer Stasov, are violently overthrown by their servants and employees. Thus, just as the introduction of Western capitalism in post-Soviet Russia radically upended the nation’s class structure, the arrival of Western capital in Of Freaks and Men instigates drastic rearticulations of the film’s social hierarchy.

Amid an array of pornographers and killers, Of Freaks and Men depicts a world devoid of any perceptible hero or positive model according to Dondurei and Mikhalkov’s terms. Although the film does at first seem to construct a dichotomy of ‘freaks’ versus ‘men’, the borders between freakishness and normality grow increasingly tenuous. As the narrative unravels, it becomes clear that, hidden beneath the intricate Baroque architecture of the city, is a sordid clandestine world and, behind the prim and proper appearances of the normative characters, lurk dark, subversive desires. Ultimately, it becomes impossible to distinguish between freaks and men as the two, once-discrete worlds, collide and finally collude. The freaks are exposed as having distinctly human weaknesses: Johann has an almost tender attachment to his elderly nanny and is so devastated by her death that he suffers a severe epileptic fit; Viktor, in spite of his ominous toothy grin and sinister expression, is painfully insecure vis-à-vis his boss Johann and has a childlike fascination with the conjoined twins Kolia and Tolia (Dyo Aloysha and Chingiz Tsydendambayev). Simultaneously, the vanguards of normativity are either killed (as in the case of Stasov and Radlov) or implicated in perverse or deviant enterprises: Ekaterina and Liza sado-masochistically submit themselves to public flagellation; Putilov assists in, and subsequently profits from Liza’s exploitation, stealing the footage from Johann’s camera and using it to become a famous director; Kolia and Tolia, become singing sideshows, coerced into touring and starring in Johann’s fetish films.

Thus the film stages a series of social upheavals and reversals of power, recalling Žižek’s description of the transition from ‘really existing Socialism’ to ‘really existing capitalism’ in Eastern Europe, which, he observes:

brought about a series of comic reversals of the sublime democratic enthusiasm into the ridiculous. The dignified East German crowds gathering around Protestant churches and heroically defying Stasi terror, all of a sudden turned into vulgar consumers of bananas and cheap pornography; the civilized Czechs mobilized by the appeal of Havel and other cultural icons, all of a sudden turned into cheap swindlers of Western tourists. (71)

A similar series of ‘comic reversals’ punctuates Of Freaks and Men; though Liza, Putilov, and Kolia and Tolia all defiantly revolt against (and ultimately unseat) the tyrants that have oppressed and dehumanized them, their fervour quickly fades as they take to consuming and participating in ‘cheap pornography’ and sideshows.

Balabanov’s presentation of the birth of Russian film is thus completely de-mythologized. He casts turn-of-the-century cinema, and the players involved in its conception, as amoral, exploitative and more concerned with films as profitable goods than works of art or experiments in the technical possibilities of the medium. Moreover, none of the characters, even those who flee St. Petersburg, seem able to escape their deviant proclivities. Tolia dies of alcohol poisoning in the East and Liza willingly re-enacts her sexual abuse (paying a sex trade worker to spank her in the front window of a sex shop) in an unspecified red light district in the West. At the conclusion of the film, no positive ‘hero’ is salvageable from the surviving cast of ‘freaks’. Like Johann, left aimlessly afloat on the ice floes of the Neva, the viewer is cast adrift in the bleak amorality of Balabanov’s post-Soviet parable.

“We’re In A Free Country Now!”: Gangsters Run Amok in the Free Market

Dead Man’s Bluff, a dark comedy that follows two inept gangster brothers trying to make it big on a drug deal gone bad, opens with a view into an economics lesson at a Moscow university. Though unrelated to the film’s central narrative, the opening episode effectively frames Balabanov’s film as an examination of free-market economics, crime and amorality in post-Soviet Russia through a farcical story of halfwit gangsters and corrupt policemen. The film, which arrived on the heels of a three-year hiatus and two unfinished projects, received far cooler responses (from both critics and film festival audiences) than Balabanov’s previous films. That the film was rather poorly received is not entirely surprising. In terms of its visual style and tone, it has little in common with Balabanov’s earlier work. It is his first comedy, the first of his films for which he did not write the screenplay, and the first not filmed by his long-time collaborator, cinematographer Sergei Astakhov. Shot over the course of a month, the film’s visual style is certainly not comparable to the elaborate mise-en-scene and striking cinematography seen in Of Freaks and Men. One critic goes as far as to claim that “to speak of cinematography in Dead Man’s Bluff is akin to discussing the brush strokes of a child’s finger-painting” (Seckler, paragraph 4). In response to these harsh criticisms, both Balabanov and the film’s lead actors have repeatedly retorted that the film was not conceived as an art house project, but on the contrary, as an intentionally poorly shot joke, a hyperbolically commercial comedy. During the film’s press conference at its premier at the 2005 Kinotavr Film Festival, lead actor, Alexei Panin, stated “It’s a joke! We’re joking in this film! The blood, the corpses-it’s comical! You need not take it all so seriously!” With sixteen theatrically bloody killings and a multitude of star cameo appearances[7] throughout the film, it seems highly plausible that Balabanov deliberately set out to create a tongue-in-cheek critique of the type of action-packed, star-studded commercial blockbusters that have increasingly dominated the Russian box-office since the late 1990s. In spite of the criticisms waged at the film, and even the filmmaker’s own assertion that it is essentially an elaborate joke, on an ideological level, I argue Dead Man’s Bluff constitutes Balabanov’s most subversive deconstruction of Russian national mythologies, the concept of the Russian national hero and Balabanov’s most explicit critique of mainstream commercial cinema in post-Soviet Russia.

Dead Man’s Bluff begins and ends in 2005, but the majority of it takes place, as a title indicates to the audience, sometime in “the mid-1990s.” The film is Balabanov’s look back, from a contemporary perspective, at the first post-Soviet decade in Russia, the period in which he first earned his reputation as an alternative Russian auteur. The tagline for the film “for those who survived the 90’s”[8] can be read as both a reference to the social and economic hardships Russian citizens faced in the 1990s, as well as to the dismal state of the Russian film industry during that time period. Like Of Freaks and Men, Dead Man’s Bluff actively questions and destablizes Russian national mythology, as well as the notion of the ‘liberating’ influence that Western democracy, and capital were to have on post-Soviet Russia. In her 2003 investigation of life in the post-Soviet era, Russia Between Yesterday and Tomorrow, Pruska-Carroll argues:

Now all Russians are free to express themselves. Freedom of expression, that tenet of Western democracy taken so much for granted, is finally a right in Russia. People are no longer afraid to speak. Moreover, they have that essential corollary to freedom of expression: access to information. In my opinion, these rights represent the greatest gain in this period of transition and the greatest hope for the future of Russia. (13)

While it is undeniable that the lifting of heavy censorship regulations and isolationist policies in the states of the former Soviet Union greatly impacted citizens’ rights to freedom of expression, the opening scene of the mid-1990s storyline in Dead Man’s Bluff calls into question this belief that Western democracy and capitalism has been a truly liberating force. Foregrounded by rows of pale corpses laid out on tables, a man known only by his moniker ‘the butcher’ (Kirill Pirogov) talks gleefully about the new post-Soviet condition exclaiming “We’re in a free country now!” while preparing to torture an anonymous man (Aleksandr Bashirov) bound to a chair in front of him. In this scene Balabanov highlights the paradox of the post-Soviet era: though it may have abolished certain communist strictures limiting citizens’ freedom of expression, it also permitted the birth of a new and highly powerful Russian Mafia. As Chenoy describes:

The weakening of the state’s role and its simultaneous withdrawal from several important functions together with the hurried reform of economic and political processes assisted the rise of the Mafia in Russian Society. The decentralization of state power and the weakening of old safety nets led to an increase in crime [… and] the respect given to capital of any kind, even illegal capital, encouraged economic crimes […] Further, the strict weapons laws of Soviet times weakened and [were] not strictly enforced. The population thus [currently] has 3 million registered weapons and several times more unregistered weapons. (225)

Moreover, while it may be true that, officially speaking, post-Soviet Russians have increased rights to freedom of expression, the fact that dozens of journalists attempting to expose corruption in the Russian government (and collusion with the mafia) have been murdered since the fall of the Soviet Union undercuts the myth that Western ideals have had a singularly liberating impact on post-Soviet society. It is precisely this irony that is played out in the film, as it is the access to and free flow of information/communication (the corrupt cop’s [Viktor Sukhorukov] discovery of a note in the pocket of the butcher’s torture victim, and Sergei and Seymon’s acquisition of the Ethiopian’s [Grigori Siyatvinda] home address) that triggers and fuels the film’s bloody spate of violent exchanges.

In terms of its discussion of economics in post-Soviet Russia, the film explores, in an exaggerated and bloody fashion, the darker side of the “redivision of property” in 1990s Russia that the economics professor discusses in the film’s opening scene. As the professor states, “startup capital is everything.” Like Johann and Viktor Ivanovich, the cast of characters in Dead Man’s Bluff (ranging from incompetent hitmen, to corrupt policemen, and garage drug lab technicians) all ruthlessly seek out this all-important capital to make a new life for themselves in this new Russia. A 2006 review of the film in The Washington Times fittingly describes it as “the story of gangsters run amok in the chaotic free-market streets of a 1990s Russia awash in American music and McDonalds.” To be sure, the film’s setting is nothing short of chaotic, as the pursuit of startup capital fuels the ever-growing death toll in the film. Balabanov portrays, in a highly graphic fashion, the “high human cost” of post-Soviet economic reforms, which made many Russians rich but also “created a vast new underclass” (Aslund and Olcott xv). In Dead Man’s Bluff, this conception of the ‘underclass’ is taken to a literal extreme, as the characters who are unable to create capital or turn a profit end up dead. In the post-Soviet world of the film, it seems Western capitalism has entrapped all of the characters in a game of ‘Dead Man’s Bluff’ (Russian roulette) as they gamble their lives for the chance at ‘capital of any kind’. As with Of Freaks and Men, characters undergo a series of ‘comic reversals’ in this game: drug lords become doormen and street thugs make themselves over into successful businessmen. However, of the few characters who manage to ‘survive the 1990s’, all remain inescapably caught in what Žižek terms a “whirlpool of ruthless commercialization and economic colonization”-the ‘vulgar consumers’ of McDonalds and American pop music (71).

The film thus aims to discredit the myth that “after the Soviet collapse a phoenix of liberal capitalism would arise from the ashes” (Chenoy 217). This ‘phoenix’ that mainstream post-Soviet heritage films seek to raise (in a glossed-over resurrection of Russia’s ‘glorious imperial past’) is nowhere to be found in Balabanov’s films; instead the transition to democracy and the free market is depicted as a violent and traumatic blow to the Russian economy and the Russian people. Finally, of the never-ending array of ruthless halfwit criminals that litter the screen, none seem to operate via any moral code whatsoever, and certainly none qualify, even remotely, as positive new Russian heroes. Gangsters and cops are different in uniform only: both are equally corrupt in their actions. Even the mafia boss’ young son appears to be completely morally detached from all of the violence he witnesses, crafting miniature cemeteries for fun. As the promotional material for the film’s DVD release states, the film is a meditation “on the mean free market streets of modern day Russia [a] circus mirror world […in which] cops, gangsters, lawbreakers and lawmakers can be interchangeable [and] the only real liberty is the freedom to kill.”

Now, nearly two decades after the Russian film industry was virtually decimated in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian directors still struggle to create films with “the power to move post-Soviet audiences back into cinemas” (Larsen 511). Nonetheless, recent Russian box office successes such as Andrei Konchalovsky’s Antikiller films (2002, 2003) and Timur Bekmambetov’s Night Watch series (2004, 2006, [the third installment of the series scheduled for release in 2009]), which outsold their American competition at the time of their respective releases, point to a potential resurgence of Russian cinema both domestically and within the international film market. Though Balabanov’s films are neither big-budget blockbusters of that ilk, nor the type of heritage film his veteran colleagues called for, they have, nevertheless, helped generate the increased presence and visibility that Russian cinema is presently enjoying at home and abroad. Rejecting the “conventional wisdom” of his cinematic peers, and instead offering a “funhouse mirror” vision of Russian history and post-Soviet life, Balabanov has attained a sort of freakonomic[9] success, examining the perverse “hidden side” of post-Soviet life (Levitt and Dubner 13-14). However, regardless of one’s personal or moral stance on Balabanov’s violence, amorality, dark and subversive subject matter, and somewhat uneven aesthetic, his films are undeniably “landmarks in the history of post-Soviet cinema” (Larsen 511) that offer a uniquely alternative (re)vision of Russian history, economics and, above all, its most important art.

Works Cited

Anders, Aslund and Martha Brill Olcott. Russia After Communism. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1999.

Beumers, Brigit. Pop Culture Russia! Media Arts and Lifestyle. Denver: ABC CLIO, 2005.

–. “To Moscow! To Moscow? The Russian Hero and the Loss of the Centre.” Russia on Reels: The Russian Idea in the Post-Soviet Cinema. Ed. Birgit Beumers. New York: IB Tauris, 2005.

Bradshaw, Peter. “Of Freaks and Men: Interview with Alexei Balabanov.” The Guardian. 14 Apr. 2000. 22 Mar. 2008. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2000/apr/14/5>.

Chenoy, Anuradha. The Making of New Russia. New Dehli: Har-Anand Publications, 2001.

Chossudovsky, Michel. The Globalization of Poverty: Impacts of IMF and World Bank Reforms. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 1997.

Chrisie, Ian and Richard Taylor. The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents 1896-1939. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Clarke, Roger. “Freaks and Filmmakers: Alexei Balabanov’s Films are Full of Prostitution, Guns and Madness. Russians Don’t Want to Know, He Doesn’t Care.” The Independent. Aug. 1999: 16.

Hashamova, Yana. “Aleksei Balabanov’s Russion Hero: Fantasies of a Wounded National Pride.” Slavic and East European Journal. 51.2 (2007): 295-311.

“Irony, Suspense, Gunplay Propel Russian’s ‘Bluff’ Running Amok in the Free Market.” The Washington Times. July 6. 2006: M24.

Larsen, Susan. “National Identity, Culural Authority and The Post-Soviet Blockbuster: Nikita Mikhalkov and Aleksei Balabanov.” Slavic Review. 62.3 (2003): 491-511.

Lawton, Anna. “Russian Cinema in Troubled Times.” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film. 1.2 (2002): 98-113.

Levitt, Steven D. and Stephen J. Dubner. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. New York: William Morrow, 2005.

Pruska-Carroll, Marika. Russia Between Yesterday and Tomorrow: Russians Speak Out on Politics, Religion, Sex and America. Montreal: Véhicule Press, 2003.

Sachs, Jeffrey. Understanding Shock Therapy. London: The Social Market Foundation, 1994.

Seckler, Dawn. “Dead Man’s Bluff.” KinoKultura. Sep. 2005. 25 Feb. 2008. <http://www.kinokultura.com/reviews/R10-05zhmurki.html>.

Stojanova, Christina. “Russian Cinema in the Free-Market Realm: Strategies for Survival.” Kinema. Spring 1999. 2 Mar. 2008. <http://kinema.uwaterloo.ca/sto991.htm>.

Žižek, Slavoj. “For a leftist appropriation of the European Legacy.” Journal of Political Ideologies. 3:1 (1998): 63-78.

Notes

[1] As stated in a 1922 conversation with Anatoly Lunacharsky (quoted in Christie and Taylor 57).

[2] In his 2006 Sight and Sound review of The Barber of Siberia, Julian Graffy argues, “for two decades, Nikita Mikhalkov […] has been the most famous and successful of Russian filmmakers in his own country and abroad” (39), having won both the Palme D’Or and the Academy Award for Burnt By the Sun.

[3] According to the 1995 Eureka Audiovisuelle bulletin, American films occupied between 75 and 85 percent of Russian cinema repertoires in the early 1990s (Stojanova 1).

[4] Many scholars have theorized that a significant number of films in this boom were simply money-laundering vehicles for private investors and members of the Russian mafia, and thus “an entirely artificial branch of industry” (Beumers 74).

[5] An economic reform model for “instantly creating a free market economy” in the post-Soviet states popularized primarily by economist Jeffrey Sachs, who theorized that “the West should reshape the life of the entire East European region” (25).

[6] Calculated in U.S. dollars. In 1993, one U.S. dollar was worth approximately 1,000 rubles (Chenoy 195).

[7] Nikita Mikhalhov, himself one of Balabanov’s most vocal critics even has a small role in the film, which further suggests that it is indeed intentionally hyperbolic and farcical.

[8] The subtitle is also ironic, given that the vast majority of the characters in the film-save the two leads and a few minor players-do not, in fact, survive Balabanov’s ‘mid-1990s’.

[9] Levitt and Dubner’s application of the analytical tools of economics to the study of a diverse range of “freakish” socio-political and cultural “curiosities.” Freakonomics has as its mandate: “stripping a layer or two from the surface of modern life and seeing what is happening underneath” or exploring, as the book’s subtitle reads, “the hidden side of everything” (13-14).

i love your sites design, did you design it by yourself? or where did you get it from? thanks in advance.