Steffen Hantke

Face pale and lined.

Flaccid mouth.

Smoothly curved jaw.

The famous mustache.

– Don DeLillo, Running Dog (235)

‘He was on again last night’.

‘He’s always on. We couldn’t have television without him’.

– Don DeLillo, White Noise (63)

Introduction: Routine Transgression

In these two passages, one from Running Dog and one from White Noise, Don DeLillo charts the discursive rules of how, more than half a century after the end of the Third Reich, the figure of Adolf Hitler is framed in popular culture. There is, on the one hand, Hitler, the cultural icon: readily represented in visual shorthand, utterly familiar and easily recognizable, a staple of public debate, endlessly explicated and commented upon. On the other hand, there is Hitler, the enigma: an elusive and incomprehensible numinous presence, the very name unmentionable, taboo, too dangerous to speak out loud. DeLillo illustrates what is clearly the discursive expression of historical trauma-a collective inability either to talk about something, or to stop talking about it.

Given this dilemma of too much or too little representation, it is hardly surprising that the prospect of evoking Hitler in a motion picture still gives pause to many producers, directors, and actors. Nowhere is this more acute than in Germany, where, understandably enough, the strictures of cultural and political decorum surrounding the representation of German fascism are more elaborate and complex than anywhere else.[1] Any film taking on this subject matter inevitably places itself in a discursive field that, more than its own deliberate and explicit agenda, will determine how it is perceived and evaluated. If not hypersensitivity, then at least interpretive hypervigilance is a crucial requirement for all those who aim to operate within this field.

Nonetheless, the difficulties with which texts have to struggle in establishing themselves within the discursive field have not been a hindrance to the production of hundreds of films about the Third Reich. The existence of a ‘Third Reich Industry’, an adjunct perhaps to what historian Norman Finkelstein has controversially described as the “Holocaust Industry”-a vast body of cinematic representations of Nazism, a substantial part of which originate in Germany-testifies to the willingness on the part of filmmakers to take the risks involved, as well as, perhaps, to a continued audience demand for such cinematic representations. In fact, one might argue that it is exactly the charged nature of the subject matter and the audience’s concomitant hypervigilance that attracts filmmakers to the subject. Making a film about the Nazis, one might easily err in a number of directions; but being altogether ignored or dismissed for one’s frivolity or triviality-that’s far less likely.

After so many films have been made about this topic-Nazi Germany and, at the heart of it, the numinous presence of Adolf Hitler himself-it is surprising that the taint of transgression is still attached to the subject matter. In fact, the discursive mechanism regulating public discourse seems capable of reconciling the regularity with which new films are being made and released on the one hand with the note of transgression that, with equal reliability, echoes through the media whenever a new film is released. If such a thing is possible, one might speak of routine transgression-a cultural reflex that, periodically revitalized by the political and social instrumentalization of collective historical memory at the hands of a variety of different social agents, never ceases to kick in when confronted with the right/-wing stimulus.

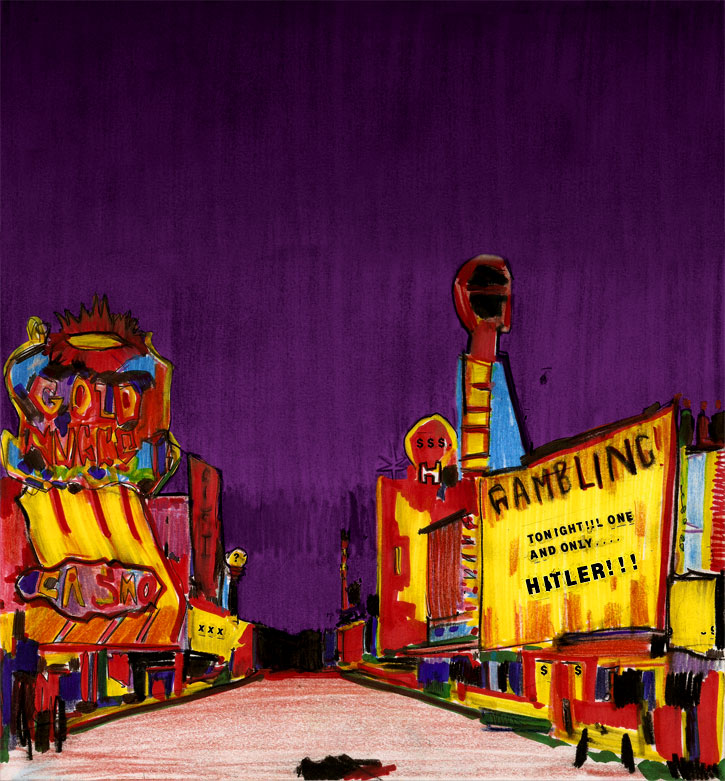

The instances in which this element of trangression strikes me as particularly interesting are not small auteurist films or low-budget paracinematic productions, which, being situated on the margins of the film industry, have the freedom to be truly transgressive, to indulge in bad taste, or to explode the regulatory framework altogether. The films I have in mind-from Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film From Germany (1977) to Christoph Schliengensief’s 100 Jahre Adolf Hitler: Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker (1989)-are the cinematic equivalent of “Springtime for Hitler,” that jaw-droppingly offensive musical thought up by a demented Nazi in The Producers (Mel Brooks, 1968). Unlike productions that aim to please a mainstream audience, these films can claim to shock, scandalize, or antagonize their audiences to a degree that would spell commercial disaster for a larger, more commercial mainstream production. It is here in the mainstream that films have to tread lightly, laying claim to the transgressive nature of the material without antagonizing their respective audiences.

An example of the regulatory framework surrounding the figure of Hitler in mainstream productions would be the rule that Hitler can never be the protagonist. Both the films I will discuss, Dani Levy’s Mein Führer (2007)and Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Der Untergang (2004) follow this rule, positing a character who serves as a point of entry for the viewer into the film and functions as a witness, observer, and narrator of Hitler himself (the Jewish acting coach Grünbaum in Levy’s film; the secretary Traudl Junge in Hirschbiegel’s). As part of its explicit intention, the device prohibits identification with Hitler by establishing a perspective of distance; nonetheless, the introduction of a perceiving consciousness also allows for the possibility of fetishizing Hitler, reiterating the idea of Hitler’s charisma, which would be far more difficult to communicate if viewers had to be enthralled by Hitler without the guiding intervention of a mediating consciousness.

These two German films-Mein Führer and Der Untergang-strike me as particularly interesting examples of this balancing act between transgression and containment. As productions located squarely in the mainstream of the German film industry, both films received a high degree of media attention for what was perceived to be a risky, potentially transgressive conceit: an intense focus on the figure of Adolf Hitler as the film’s central character. More specifically, both films explore-or exploit-their unique use of the figure of Hitler as the hook or punch line of what new Hollywood has been calling “high concept.”[2] Responding originally to television’s need to summarize an entire film in a thirty-second advertising segment, the term is linked largely to the Hollywood blockbuster. Though neither one of the two films falls, strictly speaking, into this category, they nonetheless provide insights into other national film industries and their appropriation and modification of the economic and aesthetic model developed in the U.S. They are, one might say, German interpretations of American ‘high concept’. This applies not just in the sense that their basic plot premise is simple and striking and easily summarized in a sentence or two (“a unique idea whose originality could be conveyed briefly” Wyatt 8), but, more importantly, to the fact that their marketability is largely “based upon stars, the match between a star and a premise, or a subject matter which is fashionable” (Wyatt 12-3). In other words, the casting and performance of the actor portraying Hitler can-and does, in these specific cases- serve as the lynchpin of the public debate as it is constructed and structured by the films’ own marketing campaigns.

Upon the films’ release, the debate was often more prescriptive than descriptive; the central question seemed to be how an actor should play Hitler: is it, for example, acceptable or politically prudent to play him sympathetically, to humanize him, or to offer, through script and performance, psychoanalytical explanations for his personality? From this debate the more central questions remained curiously absent: how did the actor actually play Hitler, and how did the film contextualize this central performance? Aside from praise or criticism for the actor in the controversial role, very little detailed description and critical analysis of the performance was actually presented. To the degree that these two questions remained unasked, and thus largely unanswered, I will try, in my own discussion of the two films, to analyze the cultural significance of casting and acting performance in Hirschbiegel’s and Levy’s films.

Mein Führer

As signaled by its playful, highly ambiguous title, Dani Levy’s Mein Führer-Die wirklich wahrste Wahrheit über Adolf Hitler [My Führer-The Truly Truest Truth About Adolf Hitler] comes across as an inventory of the tropes and themes assembled in various configurations by all preceding cinematic representations of the Third Reich and, more importantly, of Hitler himself. Its basic premise-a Jewish actor is recruited by Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth) from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, three months before the inevitable collapse of Nazi Germany, to coach Hitler for a final rousing speech to the harried citizens of the ruined Berlin-helps to unfold some of the meanings of the film’s title. Based on the formal address to Hitler by all those in close proximity to him, the possessive pronoun “my” in “my Führer” points to the fact that, at the end of the coaching process, Hitler is, in fact, the product of his Jewish acting coach, Professor Adolf Israel Grünbaum (Ulrich Mühe)-a fact the film literalizes by having Grünbaum, hidden from view, speak the words that Hitler himself, having lost his voice, is incapable of uttering. This act of ventriloquism, the title suggests, also applies to Levy himself, who acknowledges that his film-any film-about Hitler is less a representation of historical fact than a personal interpretation.[3] There is no Hitler; there are only multiple ‘Hitlers’, and each one is always only somebody’s Hitler.[4] “In 100 years, authors are still going to write about him,” Grünbaum’s melancholic voiceover from beyond the grave closes the film, “actors, great ones and hams, are still going to impersonate him. And why? Because we want to understand what we will never understand.”

This Beckettian pronouncement at the end of the film, with its mixture of futility and resignation on the one hand and obsessive determination to continue on the other, explicitly recognizes that all representations of Hitler exist in an enclosed discursive field from which there is no release. Consequently, the film is full of intertextual references to its predecessors: every comically extended barrage of Hitler salutes brings to mind Lubitsch’s To Be Or Not To Be (1942); in the scene in which Hitler greets Grünbaum for the first time, he stands next to a globe reminiscent of the one with which Chaplin’s Hitler performs the famous balletic sequence in The Great Dictator (1940); the final scene in which Grünbaum ventriloquizes for Hitler hidden underneath the speaker’s podium harks back to the scene in Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum (1979) in which Oskar Matzerath disrupts a Nazi rally by, literally, having the assembled guests dance to a different beat (halfway through Hitler’s own speech, Grünbaum abandons the script and begins, instead, to speak truth to power, deriding Hitler’s audience openly for their uncritical support of the regime and its obviously insane leader, which costs him his life).[5]

Grünbaum’s final voiceover is also symptomatic of another aspect of the film’s central conceit: though rife with symbolic and metaphoric significance, the film does not encode its figurative content but projects it onto the allegoric surface. Symbols and metaphors are always clearly marked for what they are; instead of letting us figure out what something means, the film will tell us. Everything is explicit, obvious, direct, and simple. Viewers are asked to recognize, not to decode. Hitler and Grünbaum, for example, are both named Adolf because they are doubles, sharing the same narcissistic mania to reshape reality to fit their own desires-this we are told explicitly by Elsa, Grünbaum’s wife, just in case we missed even the none-too-subtle play on the shared name. Just as Grünbaum’s final voiceover, addressed directly to the audience, didactically articulates what a more modernist aesthetic would have communicated more subtly or obliquely. The film openly reiterates, time and again, its point that Nazism is essentially a hollow spectacle, a performance which, despite the awful actors enlisted to enact it, has the power to lead nations to their doom. Goebbels’ remark to Grünbaum, delivered with a knowing wink-“staged reality: your and my special area of expertise”-is repeated for emphasis.

This self-conscious aesthetic places the film’s tone squarely in the tradition of farce. Goebbels’ indefatigable womanizing; Himmler’s arm in a brace, suspended in a bothersome perpetual Nazi salute; Hitler’s conciliatory remarks to Grünbaum about the Holocaust (“Please don’t take it personally”); the punctuation of the conversation between Hitler and Grünbaum with sight and sound gags from Blondie, Hitler’s German Shepherd; the scrawny soldier sporting an exact replica of Hitler’s own mustache; two Nazi officers bickering about a missing form while being strafed and bombed by an enemy fighter plane; the switching of identities in Grünbaum’s final act of ventriloquism-all of this is blunt, clunky humour straight out of the playbook of farce.[6]

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that, as an exercise in postmodern storytelling, the film is not committed to this farcical tone; instead, it is free to change pitch, shift register, and switch genres. The danger to Grünbaum’s family is all too real and Grünbaum himself is a tragic figure. There is much in the film that is intended to move the audience with an unironic emotional intensity inverse to the levity of farce. Similarly, the film’s insistent psychoanalyzing of Hitler, framing him as an abused child acting out its infantile psychoses throughout its ascendancy to the stage of world history, comes across as incompatible with the thrust of farce. As Hitler reveals this childhood trauma in his weaker moments, Grünbaum, the narrative’s moral center, shows empathy for the abused child-a response that, again without a hint of irony, invites the audience to share this empathic sentiment. Critics have remarked upon the dissonance between these moments of empathic intensity and the farcical tone in which they are embedded, complaining that Levy fails to find the right tone or, having found it temporarily, fails to sustain it properly.[7] This criticism, however, applies only if one assumes that the film, in modernist fashion, looks for a grounding reality beneath all the shifting layers of representation-which is obviously not the case. Ultimately, we are not to decide whether the psychoanalytical approach is valid or not, but simply to acknowledge it as one of the vast number of elements that constitute the discursive field.

What makes this exercise in postmodern ambiguity palatable to a large audience, however, is Helge Schneider in the role of Adolf Hitler. Schneider’s casting, on par with the surreal absurdity of the Jewish actor coaching the Nazi leader, is what makes the film high concept. Public discussion of the film before its release was centered almost exclusively on this fact; reviewers tended to spend considerable time on what might have prompted Levy to pick Schneider for the part, and whether the ‘actor’ had pulled it off; and in the marketing and packaging of the film, its central casting choice took up considerable time.[8]

Audiences outside of Germany-who are not familiar with Schneider’s persona from his standup comedy and performance pieces, especially since the early 1990s-will have difficulties grasping the weirdness of the man and his act. Much of Schneider’s persona is defined by a lowbrow tone, verging on the infantile, which will often extend its own tongue-in-cheek knowingness to the audience only to retract it at the last minute, leaving viewers uneasy about the lack of sophistication of the performance. Delivering kitschy sentimentality with a straight face, often in the form of a smarmy pastiche of kitsch phrases, Schneider’s performances are neither satiric nor nostalgic. Similar to American standup comedians like Gilbert Gottfried, Schneider almost never abandons this persona in public, carrying it over and sustaining it as he has moved from music (where he can provide sterling credentials as one of Germany’s prime jazz pianists), to standup, to writing novels and musicals, and, finally, to character acting.[9] With Schneider being such an unlikely choice for the role of Hitler-if not a gross act of intentional miscasting, as some reviewers continue to insist[10]-the film not only announced its aesthetic agenda; it also channeled its own reception toward Schneider’s performance.[11]

Consequently, the long wait, which the audience is expected to endure before they get to see Schneider as Hitler for the first time, is not in anticipation of Hitler, the character, but of Schneider. The montage of archival footage of Hitler that opens the film sets the visual standards of the performance to come, extending a challenge to the actor, and building audience anticipation. After we have seen the historical figure, we must now wait to see the actor playing him. The strategic delays written into the opening events (phone calls being made, forms being stamped, and double-stamped, and stamped again, and a Jewish prisoner being removed from the camp) culminate in a scene in which Grünbaum, flanked by guards, walks into the doorway that leads to the room in which Hitler awaits him. Levy has Schneider stand at the far end of the room, shooting him in a long deep focus shot, maintaining the doorway as a proscenium arch around the configurations of characters. When the film cuts to a reverse-angle shot, Schneider’s profile, down to the shoulders, is visible in the foreground, but since this is not a deep focus shot, it withholds a clear view of his features; though clearly visible in its outlines, the face is not discernable in sufficient detail. Just as Schneider has top billing in the opening credits, Levy gives him-Schneider, not Hitler-a memorable star entrance.

Once he has entered the film, Schneider’s Hitler is visually circumscribed by the heavy facial make-up the actor is wearing. The layers of latex, which give Schneider’s face a heaviness and jowliness it does not naturally possess, draw attention to themselves as external prostheses, even though they are, ostensibly, applied expertly and designed to be invisible as such.[12] The fact that the prostheses show-and that they are made necessary by the absence of any natural similarities between the actor and the man he plays-signals, yet again, the constructedness of the figure. Schneider’s acting is equally self-conscious and deliberately heavy-handed. He does not, in the proper sense, ‘play’ Hitler; there is little interpretation going on. Rather, he ‘does’ Hitler, impersonating him, assembling a character that is pulled back from caricature by the impossible and outrageous situations in which the script places him: Hitler in the tub playing with a model battleship; Hitler in gym clothes feigning boxing moves before accidentally being knocked out by Grünbaum; Hitler sneaking out of the chancellery in the middle of the night, dangling his dog by its leash from a ledge; Hitler crawling into bed with Grünbaum and his wife.

This deconstruction of the historical character, and its replacement with ‘Schneider’s Hitler’, culminates in a scene at New Year’s Eve in which Hitler sits at the harmonium and plays music for Eva Braun while, in the background, a film reel is playing that shows ‘Kraft Durch Freude’ footage of scantily clad Aryans frolicking in Nature. Hitler’s love song to Braun is delivered in a halting, adenoidal, half-spoken singing voice, and its lyrics are composed of awkwardly phrased, clunky, hammy sentiments-this is not Hitler, this is Helge Schneider, the standup comedian, striking the signature tone of his public performances. The cognitive dissonance is exacerbated by the archival footage of Hitler himself that appears on the screen as Schneider gets up from the harmonium, gives the Hitler on the screen a friendly nod, and then sits with Eva Braun. In a scene like this one, it becomes obvious that Levy’s decision to cast Schneider, as well as Schneider’s performance, are perfectly consistent with each other. The film’s balancing act between incompatible emotional registers and modes dovetails with Schneider’s own performance, in which-exactly as in his previous performative work and his public persona-satiric and sentimental tones are played against one another.

Der Untergang

Though Der Untergang could not be any more different in tone and acting performance from Mein Führer, Oliver Hirschbiegel’s film allows itself a touch of irony every now and then: four soldiers carrying two huge wooden crates with the word “Fragile” stenciled on their sides through heavy artillery shelling; Hitler discussing calmly the best way to shoot yourself in the head with a group of mostly female dinner guests in a polite petit-bourgeois living-room setting; Eva Braun admitting that she is jealous of Hitler’s German Shepherd Blondie; the government official recruited to perform the wedding of Hitler and Eva Braun nervously explaining how he is required by law to ask Hitler whether he is of pure Aryan descent; etc. But the humour in these moments never transcends the grimness of the context, historical and atmospheric. Though momentarily alleviated, tragedy is never abandoned. There is a gallows humour in the film, but it belongs to the characters and their situation, and never to a detached observer or authorial voice looking in on, or down upon, the diegesis.

To use the term ‘high concept’ in regard to Der Untergang is perhaps less immediately obvious as in the case of Mein Führer. Casting is not the film’s central conceit, narrative focus is. For the entire length of the film (156 minutes, 178 in the extended cut), we are in the bunker underneath the chancellery, in the presence of Adolf Hitler himself, witnessing the final few days before the collapse of the Third Reich. This is, of course, not entirely true: we do leave the bunker, we do follow other characters (quite a few of them, in fact), and we do go on for well-nigh an hour after Hitler’s suicide removes him from the story. Nonetheless, it has always been this tight focus-tightened further by oversimplification-that has elevated the film to high concept. Hence, the film is, or has been consistently framed as, a piece of theatre. Promising to draw us into close proximity or even intimacy with Hitler himself, the film is a Kammerspiel, exploring the psyche of a single character under extreme duress.

What complicates this categorization of the film as a Kammerspiel, and appears to stand in direct contradiction to the essential austerity of the form, is the fact that Der Untergang is also an expensive spectacle, conceptualized, financed, and designed on the level of the blockbuster. This applies not only to a large all-star cast, drawn from the crème of the German film industry, but also to a vast number of extras that appear whenever the film cuts away from the limited spaces and ensembles in the bunker to the streets of Berlin where the last battle of the German Wehrmacht against the Red Army is in full swing. Instead of integrating these events into the film by way of teichoscopy, as any production on a smaller budget would have been forced to do, Der Untergang takes us out into the streets, opening up the claustrophobic space of the bunker and delivering crowd scenes and military action as part of sweeping historical events played out on impressively large sound stages and back lot sets.

This decision to finance and market the film as a German blockbuster cannot be credited to director Oliver Hirschbiegel, whose previous two films were the mid-budgeted political thriller Das Experiment (2001) and Mein letzter Film (2002).[13] Especially the latter of the two, a digital diary shot entirely in POV of the actress Hannelore Elsner, suggests that Hirschbiegel’s qualifications as a director of the intense personal Kammerspiel were what lead to his being hired for Der Untergang. Making up for Hirschbiegel’s relative inexperience with large-scale productions is the film’s producer, Bernd Eichinger. With films like Wolfgang Petersen’s The Never Ending Story (1984), Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Name of the Rose (1986), Bille August’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow (1997), and, more recently, Tom Tykwer’s Perfume (2006) under his belt, Eichinger has specialized in high-profile productions, financed and packaged in synergy with multiple European and American partners and aimed at a global marketplace. Part of his professional profile as a commercially successful producer is also to entrust popular middlebrow literary source material to the most ‘Americanized’ European auteurist directors and then market the product in competition with Hollywood blockbusters. How much Der Untergang is a product of its producer rather than its director is signaled by Eichinger’s top billing in the opening credits, a billing he shares only with the production company’s name.

As much as Eichinger is a man of big, loud, busy movies, he takes great care in Der Untergang to situate the film in two cinematic and/or theatrical traditions with more legitimate claims to cultural capital than the blockbuster-the psychological drama in the theatrical tradition of the Kammerspiel, as mentioned before, and the documentary. The film is based on the book by Joachim C. Fest, a respected German public intellectual and historian on par with Sebastian Haffner or Golo Mann.[14] Unattached to any institutional academic context, Fest’s image as a public intellectual does, however, gravitate toward the popular, putting him in the company of media figures like Guido Knopf and Jörg Friedrich-popularizers of history more than historians in pursuit of academic careers. Though his supporters would stridently deny this claim, Fest has published a well-received autobiography in 2008-a fact that suggests that his role in German culture is less that of anonymous conduit of historiographic research and more that of a celebrity. Through interviews and public appearances, Fest has also contributed substantially to the advertising campaign for Der Untergang. Aside from the prominence of Fest among its promotional materials, the film also makes reference to Traudl Junge, Hitler’s secretary, whose appearance in the documentary Blind Spot-Hitler’s Secretary (André Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, 2002) is explicitly referenced in the film’s prefatory sequence that features Junge in a brief interview clip (before the film replaces her with Alexandra Maria Lara, the actress playing her). Inserts informing the audience of the time and place of events, as well as an insert sequence detailing further events after the closing of the film, also establish formal links to the documentary form.

The tension-between the spectacular and the sedate, between the blockbuster and the Kammerspiel, between producer and director, between fiction and documentary-is also articulated in the film’s central performance by actor Bruno Ganz playing Hitler. A veteran of the New German cinema (Herzog, Hauff, Wenders), with extensive theatrical credentials, Ganz has been a star of European cinema for decades. Despite occasional forays into the American film industry, comparable perhaps to his East German colleague Armin Mueller-Stahl, Ganz has remained a character actor, specializing in subtly nuanced performances, none of which had previously aligned itself with high concept projects.

How Hirschbiegel used Ganz is perhaps easiest to describe in the opening scene-a scene analogous to the star entrance Levy grants to Schneider in Mein Führer. In this scene, the camera attaches itself to a group of young women who, flanked by armed soldiers, are walking single-file through the winter woods. An insert POV shot reveals, in medium close-up, the unreadable face of a soldier shining a light into the young women’s eyes, while another medium shot shows the back of a soldier walking ahead to lead the way. The group enters a building, as a caption tells us the time and place of the events: “November 1942, Führerhauptquartier ‘Wolfsschanze‘, Rastenburg, Ostpreussen” [Führer Headquarters . . . East Prussia]. Having taken a seat, the women are told by an officer, “We have to ask you to be patient for another moment. The Führer is just about finished feeding his dog.” The delay is stretched out while the women ask how to address Hitler properly. As the officer opens a door, the women, still lined up, crane their heads to look past him through the open door. At this moment, the actor’s back is framed in the doorway in a manner that invites a look past him into the room on the other side of the door, and yet blocks that view. As he takes a step forward, the film cuts to a reverse-angle shot of the women, confirming our attachment to their perspective, then cuts back to the doorway, to the women, then back to the doorway again, and holds the shot for a moment. Only then does Ganz, framed by the doorway, make his entry, left to right, into the film. In a subtly low-angled shot, the camera pans to the right, keeping the medium shot centered upon him until he stops moving and begins speaking, welcoming the women.

Hirschbiegel’s visual decisions in this scene set the tone for the rest of the film. Narrative progression is intensely dramatic, almost melodramatic. Repeatedly, the appearance of what is clearly posited as the scene’s visual center is delayed. Like the women, we are made to wait. When the opportunity to steal a glance materializes, it fails to satisfy the curiosity it has stimulated. This anticipatory structure of the scene is indebted to the star entrance, linking Hitler to the discourse on celebrity. But it also derives from the visual logic of the horror film, which similarly delays the appearance of the monstrous entity at the center of its narrative. Conventional horror films, from Val Lewton’s 1940s RKO films to modern horror films like Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), keep the monster out of sight for as long as possible, staging its first appearance as an intensely overdetermined moment.

And yet every moment in the opening scene of Der Untergang is structured in a manner that downplays the melodramatic impact it is so obviously trying to achieve. First, there is the fact that the scene comes so early in the film-unlike Levy, Hirschbiegel does not make us wait too long. Then there is the scene’s emotional flatness, which is not motivated by the idea that the women are disappointed because, having finally met Hitler in person, he has fallen short of their expectations; when he enters, we do not see him in a subjective POV shot, and when we do see the women, they are obviously nervous, impressed, or even awed. Nonetheless, the scene is masterfully concealing its intense desire to thrill, masking its voyeuristic excitement behind a carefully constrained aesthetics-medium shots instead of close-ups, just a hint of a low angle instead of a more self-consciously expressionistic angle, inconspicuous flat lighting without the use of key lights, a lateral pan instead of an emotionally more intense series of cuts culminating in a close-up or even extreme close-up on Hitler’s face.[15] Though Hirschbiegel eschews the explicit trappings of the documentary, which he reserves for later scenes in the film, he does adopt an attitude of objectivity, of moderate interest, of cautious detachment that is reminiscent of the documentary impulse to record rather than interpret empirical reality. Contrasted with the building of narrative suspense, this formal restraint registers all the more as a conscious effort to balance competing impulses. This is a film that is intensely excited but trying not to look it.

Let me cite another scene in which Hirschbiegel finds this point of equipoise between excitement and detachment, that of Hitler’s suicide, which occurs about forty minutes before the end of the film. The scene redeploys the visual motif of the doorway, extended into a series of successive doorways, which, introduced in the opening scene, recurs throughout the film. Hitler and his now wife Eva Braun walk out of their final dinner with their staff, as doors close behind them. In a centered long deep-focus shot, the camera peers down hallways and through doors when the fatal shot is heard. When the bodies are removed, invisible under blankets, the camera is in medium-long shot, simulating a subjective POV of one of the lesser bystanders. Eventually, Traudl Junge visits the room in which the suicide occurred: the camera pans across ominously trivial details of furniture and décor, halting briefly as it spots blood, the gun, cyanide capsules. Detached from the momentary POV shots, however, the visual representation of the suicide is as flat in style and tone as the opening sequence. On the one event that holds the highest degree of fascination for most viewers, the film remains visually reticent. One might read this reticence as tact or decorum, or as a concession to the lack of reliable historical data and thus to historiographic accuracy. And yet the effect of this strategy does not distance viewers, neither from the events nor from their own visual desire.[16] On the contrary, their curiosity is intensified, even past the moment of the gunshot-will we or won’t we see?-and thus ultimately exploited.[17]

Both the excitement and its containment are ultimately drawn toward the center of the film, Bruno Ganz’s performance as Hitler.[18] Aided by an ever-attentive camera, Ganz’s performance assembles appearance and body language, as well as face and voice, into an impressive mimicking of the Hitler known from documentary footage. Instead of using prosthetics to increase the similarity between actor and character, Ganz concentrates on the pathology of Hitler’s body: the palsied twitching of one hand steadied by the other behind the man’s back, the complacently self-absorbed vanity of rearranging a strand of hair and smoothing it down, the forward bend of the body that has the shoulders hunched up inside a uniform that rides uncomfortably up the back. Though the parodic, almost anarchic exuberance of Schneider’s portrayal is absent, Ganz’s performance does not come across as subtle. Though it is clearly not overplayed, it still emphasizes and highlights traits it considers essential, educating viewers on what deserves attention and what does not. Whenever Ganz decides to reign himself in and hold back, the camera takes over in completing the didactic thrust of the performance, tracking and tracing each gesture with endless fascination, putting it on display with self-congratulatory demonstrativeness.

Like Schneider in Levy’s film, Ganz does not aim to discover anything new about Hitler; he only illustrates what we already know. Skilled as he is, he runs through an inventory of familiar gestures and moments, offering one more interpretation of the historical Hitler that was already part of the discursive field before the film came along. Scenes that hit one of the thematic key points are immediately recognizable: at one point, the audience is asked to contemplate Hitler as a kind elderly man, capable of compartmentalizing his private and his public persona; another scene poses the challenge to the audience to feel pity for a man who knows that he has lost everything and is about to die. Ganz’s acting illustrates these points, moving seamlessly along the basic premise of psychological compartmentalization. Consequently, the highlights of Ganz’s performance often coincide with moments of extreme rage and choleric explosion: Hitler ranting and raving, foaming at the mouth, exhausting himself in intense verbal and gestural frenzy.

Even though this performance largely reiterates all the performative aspects of Hitler that audiences are familiar with from documentary footage, it is the unchallenged center of the film. Hirschbiegel rarely shows Hitler alone but always surrounds him with groups of people, who serve as an audience not only for Hitler, but also for Ganz and for the film’s viewers. As Hitler rants and raves, they are impressed, cowed, touched, awed, and it is their response to Hitler-like the screaming chambermaid who has opened the door behind which the monster of the horror film is lurking-that models our response to Ganz.

A highly regarded veteran actor in charge not only of his performance but also of his career, Ganz must have been worried before accepting the role-more so than Helge Schneider. To a lesser extent, there is the question of what impact playing Hitler would have on anyone’s career (where do you go from there? what will audiences remember about you as an actor?), but more importantly there is concern that the performance in Der Untergang, part and parcel of a high concept film of blockbuster proportions, might be perceived as showboating, hamming it up, chewing up the scenery. Erroneous or not, audiences might perceive and interpret a performance of this intensity as a direct result of having the dramatic burden of the entire film placed on one actor’s shoulders-and that actor overreacting to, overcompensating for, the enormous responsibility.

Der Untergang anticipates this critical reaction and pre-emptively reroutes it into an engagement with the theatricality of Hitler himself, as well as the whole iconography of the Third Reich. Along with constantly surrounding Hitler with an audience for which he performs, Der Untergang is permeated with the vocabulary of the theatrical stage, of actors performing and audiences watching. We see, for example, Albert Speer (Heino Ferch) advising Hitler on the question of whether he should escape from Berlin while there is still time: “Sie sollten auf der Bühne stehen, wenn der Vorhang fällt” [You should be on stage when the curtain comes down]. In the opening scene, Traudl Junge announces her being hired to her fellow applicants by using the expression ‘engaged’ instead of ‘hired’, as if she is an actress rather than a secretary. And, as things inside the bunker grow increasingly grim, we see Magda Goebbels (Corinna Harfouch) lining up her children to perform songs for everyone’s edification in what comes across as a complex grim intertextual replay of The Sound of Music.

On this thematic level, the film merges Ganz’s performance with that of Hitler. The actor is freed from the suspicion of showboating because the character he plays is a ham. Without demanding from Ganz an unconscionable emotional effort and investment in the role, Hirschbiegel has created a situation in which Ganz can claim the supreme accomplishment of the method actor-total identification with the role-without Ganz having to perform the professionally and morally dubious task of ‘becoming Hitler’. The film itself allows the audience to contemplate both Hitler’s and Ganz’s performance with fascination. Criticized for the exploitation of Hitler, the filmmakers can shift into the register of the actor’s performance; criticized for the showboating performance, they can shift into the register of historical accuracy. Unassailable from either side, the film maintains a strategic balance.

Conclusions

If one were to take the conceit of Mein Führer seriously, then a high modernist undertaking like Der Untergang would have been made culturally irrelevant by its postmodern successor. The latter’s highbrow ambitions (or pretension, depending on one’s point of view) and adherence to empirical accuracy, signaled by its marshalling of celebrity historian Joachim C. Fest, would seem like an outdated gesture compared to the former’s playful summary and manipulation of historical iconography. Mein Führer comes along with the self-confidence of being the culturally more comprehensive take on the topic, the happily realistic final word in a world without final words rather than the grimly despondent grappling with empirical imponderabilities.

And yet, as I tried to show in my comparative reading, both films are operating at different points of what turns out to be the same spectrum of cultural production. High concept filmmaking, previously the domain of large commercial Hollywood productions, serves as the unifying factor. To the degree that the hook for a high concept film can be drawn from the repertoire of national, or even international, historical iconography, high concept is not limited to a certain stratum of cinematic production. In fact, it seems capable of reconciling directors with auteurist credentials and producers with mainstream ambitions into projects that transcend the boundaries between high-, middle-, and low-brow altogether. Just as Helge Schneider’s star persona is constructed around the transgression of such social boundaries, so Bruno Ganz’s appeal as a ‘movie star’ is tempered by his reputation as, primarily, a character actor dedicated to self-effacing performances. Under the umbrella of high concept, both Mein Führer and Der Untergang manage to harness such disparate elements that their respective appeal goes to various demographics of a larger mainstream audience.

It is possible to see in these two films examples of a new form of European filmmaking-not only in the sense that they combine the construction and affirmation of national historical identity for their domestic audience with a wider reach for international markets in which this identity is packaged as an advertisement for the national film industry that produced it. It is in this context that the endless string of German films about the Third Reich (with the occasional film about the former East Germany thrown in for good measure) that are ceaselessly being fed by their producers into the international festival and awards circuit must be understood. On an international stage, high concept transcends, for example, the unique cultural decoding skills that only the German audience will bring to Helge Schneider’s performance; high concept transcends the taint of sensationalism and exploitation that still hangs around films about Hitler and the Third Reich.

High concept also seems to provide a viable method of approach to complex and, at times, dangerous subject matter. It delivers a spark of daring experimentation and non-conformism, or even an open challenge, to a discursive field which has integrated gestures of transgression into its inventory of acceptable rhetorical moves as a matter of routine. The assembly of diverse elements-in casting, production value, actors’ performances, and marketing-under the umbrella of high concept allows for the construction of controversy, as much as for pre-emptive moves in regard to the anticipated criticism that this controversy might elicit. High concept, in other words, allows for a balance between the unique and the conventional. It puts a new spin on old material, but it also puts the reins on the outrageous.

Notes

[1]On the commentary track to DVD release of Mein Führer, Dani Levy remarks, for example, that he considers cinematic representations of the Holocaust as “presumptuous,” given the impossibility of representing something that is essentially unrepresentable. “No representation of this reality can even approach this reality . . . And then there I was, on the grounds of the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, with actors in makeup and costume…”

[2] For a more detailed definition, which includes further bibliographic references, see Blandford, Grant, and Hiller, “High Concept” in The Film Studies Dictionary (121).

[3] Though Levy makes it explicit and explores it playfully, the idea itself has already been part of the discursive field. Rudy Koshar, in a 1995 essay on Syberberg’s Hitler, points out that “Syberberg himself argues that his film is only marginally concerned with the Hitler of Nazi Germany, being a representation of the ‘Hitlers’ that appear in different historical contexts; it is a film from Germany, not about it” (Koshar 156). I am citing Koshar on/and Syberberg here not to show that someone has beaten Levy to the punch, but to underline my argument that Levy’s film is not out to break new ground but to reiterate, explode, and reassemble the elements that constitute the discursive field, regardless of its own originality.

[4] To the extent that he has lost all will to lead, the film’s Hitler is also to a large extent the product of Joseph Goebbels, who sets his restoration at the hands of Grünbaum in motion, and, unbeknownst to everybody else, plots a final act of assassination in which Grünbaum will serve as scapegoat. In the final scene, Hitler speaks not only with Grünbaum’s voice, but also-having lost his own mustache in an accidental swipe of the hand by the woman prepping him for the rally-wears the mustache of one of his guards glued under his nose (visually, a reference to Groucho Marx’s proudly fake mustache).

[5] Since the closing scene returns to the opening sequence, which has Grünbaum, blood trickling down his face from having been shot below the speaker’s podium, we know that Grünbaum narrates the film from beyond the point of death-a gesture reminiscent of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950).

[6] This is perhaps where Levy is most susceptible to criticism: many of these jokes are, arguably, in poor taste. Some critics have pointed out that Levy, who had been commercially and critically successful with farce in his previous film (Alles auf Zucker [2004], the story of greedy relatives who must adopt Judaism in order to inherit a fortune), is often granted more leeway than other directors with this combination of tone and subject matter because he himself is Jewish (“As a filmmaker with Jewish roots,” Jörg Buttgereit-himself no stranger to controversy-argues in his review of the film, “Levy could have gotten away with a lot” (Manifest 2007).

[7] Derek Elley, for example, writes in taz echoes this negative sentiment: “Additionally the film is weighed down by the awfully unfunny mix of low comedy and framing ‘melodrama’, which does not work for one single instant” (January 12, 2007).

[8] On the commentary track to the DVD of the film, Levy raves about Schneider’s performance: “this subversive comical approach he has to the role; this anarchic element in his interpretation; this unyielding, detailed, minute deconstruction of this character-this is what I find simply spectacular! . . . I’m sorry if I’m raving about the film, but I am, now more than ever, still convinced that Helge Schneider was the best choice for playing Adolf Hitler.”

[9]> To consider Schneider a star in the sense in which, for example, Richard Dyer uses the term, is problematic: despite the consistency of Schneider’s persona, which functions within systems of branding and marketing, he has largely resisted the integration of his private life into his performance. His cutting across different forms of artistic expression also complicates matters, simultaneously challenging the integrity of the persona construct and confirming it. For further glimpses into Schneider’s impressive creative output, see his home page at http://www.helge-schneider.de/.

[10] See, for example, Christoph Petersen, who initially appears to approve of Schneider’s casting (“In the beginning, courage triumphed as cult comedian Helge Schneider was brought on board”), but then comes around to lament that Levy “apparently didn’t have a clue what to do with this performance” (Filmstarts.de).

[11] This performance has sustained such media appeal that not even the subsequent death of actor Ulrich Mühe, who plays Adolf Grünbaum and who came to stardom when Das Leben der Anderen [The Lives of Others] (Florian Henckel Von Donnersmarck, 2006) won the 2007 Academy Award for Best Foreign Picture, has managed to shift attention from Schneider to Mühe.

[12] For a more in-depth discussion of the aesthetics of special effects, particularly in regard to their suspension between invisibility and conspicuousness, see Steffen Hantke, “Consuming the Impossible Body: Horror Film and the Spectacle of Cinematic Special Effects” in Paradoxa: Studies in World Literary Genres 20 (Fall 2006), 66-80.

[13] I have commented in more detail on Hirschbiegel’s and its significance as a statement on postwar German identity formation in “The Origins of Violence in a Peaceful Society.” Kinoeye: A Fortnightly Journal of Film in the New Europe 3.6 (May 26, 2003).

[14] Published in 2002, the book is entitled Der Untergang: Hitler und das Ende des Dritten Reiches. Eine Historische Skizze Downfall: Hitler and the End of the Third Reich. A Historical Sketch], and has gone through six printings so far, the last of which is marketed by Rowohlt, the publisher, as a movie tie-in. Fest also appears, together with Eichinger, as the author of the ‘film book’, also published by Rowohlt.

[15] One might think of the famous three-step editing sequence, from medium long shot to extreme close-up, in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) in the scene in which we first see Boris Karloff in Frank Pierce’s iconic make-up.

[16] For an example of how this strategy manifests itself verbally, as part of a film’s advertising and distribution, see Heinrich Breloer’s TV miniseries on the premier architect of the Third Reich Speer und Er (2005), in which Tobias Moretti plays Hitler, and in which, significantly, even Hitler’s name is omitted from the title and replaced by the numinous ‘He’.

[17] Hirschbiegel’s stylistic decisions are also reminiscent of the playbook by which American directors would outmanoeuvre the restrictions of the Production Code (one might think of the murder scene in Wilder’s Double Indemnity [1944] and the intensification of the tension between what is inside and what is outside of the frame in, for example, the torture scene in the opening of Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly [1955]). If Hirschbiegel was inspired by these stylistic solutions, his own film strips the style of its historical context and justification. Der Untergang is as bloody and visually explicit as a film can be outside the limits of active censorship, which frees the style itself to serve whatever other agenda it appears suitable for.

[18] After Ganz exits the film, i.e. when Hitler commits suicide, the theatrical cut of the film runs for another forty minutes, shifting its narrative focus, which had been attached to Traudl Junge in the opening scene, to her once and for all. It is her escape from Berlin at the very end of the film-shot on location and in natural sunlight for the first and only time-that closes the narrative.

Works Cited

Blandford, Steve, Barry Keith Grant, and Jim Hillier. “High Concept.” The Film Studies Dictionary. London: Arnold, 2001. 121.

Buttgereit, Jörg. “Review of Mein Führer.” Das Manifest: das filmmagazin. 1 Jan. 2007. 2 Nov. 2008. <http://www.dasmanifest.com/01/meinFührer. php>.

DeLillo, Don. Running Dog. New York: Random House, 1978.

–. White Noise. New York: Viking, 1985.

Elley, Derek. “Mein Fuhrer: The Truly Truest Truth About Adolf Hitler.” Variety. 17 Jan. 2007. 20 Nov. 2008. <http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117932476.html?categoryid=31&cs=1&p=0>.

Fest, Joachim C. Der Untergang: Hitler und das Ende des Dritten Reiches. Eine Historische Skizze. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 2002.

Ihle, Christian.”Mein Führer.” taz. 12 Jan. 2007. 19 Nov. 2008. <http://blogs.taz.de/popblog/2007/01/12/mein-Führer/>.

Koshar, Rudy. “Hitler: A Film from Germany: Cinema, History, and Structures of Feeling.” Revisioning History: Film and the Construction of a New Past. Ed. Robert A. Rosenstone. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995. 155-74.

Petersen, Christoph. “Review of Mein Führer.” Filmstarts. 1 Nov. 2008. <http://www.filmstarts.de/kritiken/42100-Mein-F%FChrerhtml>.

Wyatt, Justin. High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

I just surft on this. I think it’s brilliant.

Reading the whole story leads me back to the times where cruelty rules in the hands of a dictator. Pretty sure everyone else was moved by this.

Any creative work dealing with Hitler and the Third Reich is akin to a minefield. How does a creative person balance the character’s nuances with the political and social expectations?

The photographs of Hitler in this article make my skin crawl.

“Its basic premise-a Jewish actor is recruited by Joseph Goebbels (Sylvester Groth) from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, three months before the inevitable collapse of Nazi Germany, to coach Hitler for a final rousing speech to the harried citizens of the ruined Berlin-helps to unfold some of the meanings of the film’s title.”

Not surprising that Hitler would use the talents of one of the people slated for murder to advance his evil mission.

Oh how I wish this whole Hitler thing were simply the figment of someone’s perverted imagination! Unfortunately, it’s all too real…