Graeme Krautheim

Frequently dubbed ‘Nazi-porn’, the cycle of Nazi sexploitation films that emerged from Italy in the late 1970s is, I argue, the most deviant and severe example of the entire medium. In this paper, I will incorporate brief excerpts from Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste and the writings of Primo Levi into an examination of this notorious cycle of films that depict excessively trivial and incompetent representations of concentration camps. Though I am referencing Italian examples as they are the most well known (and explicit), this type of film has been linked to several national cinemas, including American and Canadian.[1] It further warrants mention that their origins date back to a literary aesthetic that is beyond my scope here.[2] It is my objective to explore how this uniquely marginal cinema not only impacts established discourses in a way unlike any other, but also destabilizes theoretical frameworks frequently taken for granted in academic circles. In a letter to the Italian newspaper La Stampa in 1977, Holocaust survivor (and author of the seminal Survival in Auschwitz) Primo Levi directly addressed the Nazi sexploitation cycle with a logic that is more relevant today than ever.[3] Levi’s discussion of the films’ ideological consequences is central to discussing their broader historical implications. To a greater extent than even slasher films or hardcore pornography, Nazi sexploitation has long been banished to the outermost peripheries of culture-a consequence of the fact that it does not merely seek to repulse, but actively incorporates inane sexual imagery to invoke an eroticized, ‘masturbatory’ reaction to the historical memory of the Holocaust. The films rely on enormously problematic historical implications which they themselves demonstrate absolutely no interest (or competence) in addressing. I base my position on what I see as a general consensus of the artistic legitimacy (or ‘cultural capital’) of Nazi sexploitation being non-existent. This provides an ideal vantage point from which to examine Bourdieu’s assertions regarding the relationship between taste and social class.

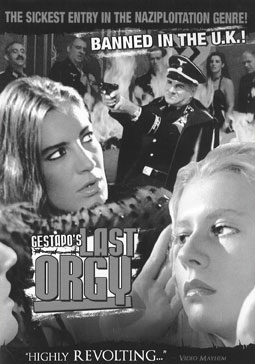

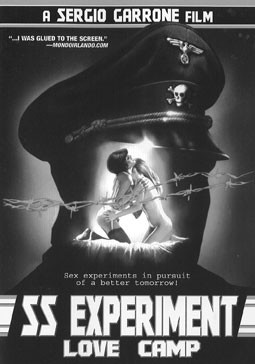

What makes an examination of this cinema timely is that, in 2005, the Exploitation Digital label released several particularly severe (and previously-unavailable) Nazi sexploitation films on glossy uncut digital DVD transfers, including SS Experiment Love Camp (Sergio Garrone, 1976) and Gestapo’s Last Orgy (Cesare Canevari, 1977).[4] The assemblage of this new DVD establishes each film as its own ‘art object’ insofar that its transference to digital media has produced the sharpest possible print and features extras, including theatrical trailers and interviews with the directors. In response to restrictions previously forced upon the films by the MPAA (X-ratings, of course), Exploitation Digital sidestepped the process altogether by releasing the restored versions unrated. What is so significant about these new transfers is how the format of their presentation has invested them with a newfound cultural value. The ‘crimes’ committed by the films coalesce into a cultural ‘hit-and-run’, where history and memory work are violated by a product designed, as exploitation films are, to be momentary and ephemeral. To carry this analogy a step further, this elaborate transfer to DVD is indicative of the films, after years ‘on the lam’, finding immunity through connections with ‘friends in high places’ (referring to the cultural-elevation of being deemed valuable enough to be worthy of such a transfer). In this capacity, not only have the films ultimately ‘gotten away with’ their ‘cultural crime’, but their transference to a fresh (and easily accessible) DVD makes their cultural capital initially difficult, on the surface, to differentiate from the important and culturally valuable films released on the Criterion label. The Exploitation Digital label has elevated these pieces of low art to such heights that they, at least via their packaging, appear to hold the same cultural stock as Triumph of the Will (Leni Riefenstahl, 1935) or Night and Fog (Alain Resnais, 1955). As vehicles manufactured exclusively for the purpose of economic gain, Nazi sexploitation films were built, first, for speed rather than distance, and second, to retain indifference toward anything they ‘ran over’ (history, memory, suffering). The Exploitation Digital label has reassembled these films (via a complete cut, in the case of Gestapo’s Last Orgy) and placed a new rebuilt engine into their bodies (via their digital transfer) that enables them to operate in contemporary culture as novelty objects.[5] With the re-release of Nazi sexploitation for a new era, we must consider both the implications related to mass consumption and memory work, and acknowledge that the easy modern accessibility of such films requires us to be responsible for and accountable to our own history in a way that we have never been before.

The historical representations themselves are frequently so outlandish and so completely divorced from all logic that they somehow defy comprehension. In these alarming and trivial representations, buxom young women (consistently depicted in various states of undress) portray prisoners in concentration camps with such stunning unwittingness that one is left pondering whether anyone involved had any knowledge of the history to begin with. The women engage in extreme and degrading sexual acts with Nazi guards, and further, are sadistically tortured and subjected to ludicrously represented medical experiments. The forced labour in the camps is depicted as though it were a series of remedial chores, and the poorly-dubbed dialogue is casual and devoid of any suffering. A grotesque banquet scene in Gestapo’s Last Orgy features a group of lust-crazed Nazis discussing a large-scale plan to eliminate the Jewish population in the camps by eating them, all the while, devouring the meat of an aborted fetus. They subsequently strip a prostitute who has fainted from shock and proceed to lustfully smother her in cognac and flambé her. In SS Experiment Love Camp,  when a German soldier realizes that he has been surgically castrated, he shouts to his superior (the recipient of the transplant), “What have you done with my balls?” These films are fundamentally indifferent to the historical context that they claim to represent, as well as to any cultural ‘damage’ they may do in the process. The representations are so humourless, incompetent and extreme that the entire filmic medium seems to collapse into a state of simultaneous nausea and delirium.

when a German soldier realizes that he has been surgically castrated, he shouts to his superior (the recipient of the transplant), “What have you done with my balls?” These films are fundamentally indifferent to the historical context that they claim to represent, as well as to any cultural ‘damage’ they may do in the process. The representations are so humourless, incompetent and extreme that the entire filmic medium seems to collapse into a state of simultaneous nausea and delirium.

Scholarly acknowledgment of Nazi sexploitation cinema has been largely limited to a discussion within the context of the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification), which introduced the Video Recordings Act in the U.K. in 1984. A movement by the conservative media fuelled a large-scale banning of (largely low-budget horror and exploitation) films dubbed ‘video nasties’ by the popular press. The initial banning of the films was based on the arguments of there being no possible reason to ‘enjoy’ them, and that the nature of their subject matter may be damaging to the minds (and moral codes) of children. For the next two decades, heavily-censored and poorly-dubbed VHS cuts of the films circulated among underground enthusiasts and collectors. With regard to other forms of exploitation cinema, I emphasize that it is Nazi sexploitation specifically that interests me, and that exploitation film as such does not apply to my position. Blaxploitation cinema, for example, has been acknowledged as important to the empowerment of Black communities, just as more conventional sexploitation films have been read within feminist scholarship as indicative of female sexual agency-although such assertions are admittedly problematic in their own right.[6] Nazi sexploitation cinema quite simply empowers no one-there is no minority for whom it speaks and no mode of discourse that would benefit from an association with it. It is vital to make clear that these films harbour absolutely no anti-Semitic or fascist sentiments. These representations are so inane, and so damaging to the credibility of anything with which they are associated, that not even those who willfully perpetuate hate or the negation of historical fact (meaning anti-Semites or Holocaust deniers, for example) would further their cause from aligning themselves with these films. Nazi sexploitation is so single-minded in its pursuit of financial profit that to deem it insidious or to accuse it of harbouring some sociopolitical agenda is to ascribe it an intelligence and ideological trajectory that it simply does not have. Made quickly on extremely low budgets, the films are so preoccupied with immediate profit that they have no comprehension of, or concern with, possible ‘costs’ to culture, memory, or for that matter, anything at all.

If Nazi sexploitation were completely divorced from the facts and circumstances of the Holocaust, it would be more easily reconciled and dismissed. These films however, make reference to actual historical atrocities, of which there are virtually no other cinematic representations. It is no surprise that cinema has never broached the subject in any serious way; the unquantifiable bodily violence inflicted upon the prisoners included (but certainly was not limited to) mass sterilizations, the severing of limbs, exposure to radiation, and the deliberate injection of diseases such as typhus, tuberculosis and syphilis.[7] In an interview on the DVD extras to SS Experiment Love Camp, Garrone situates his film within a historical framework: “When I was offered this film, I did research with authentic documents.” However, with regard to the film’s depictions of torture and graphic medical procedures, he states, just moments later, “If you don’t have ideas, you just throw in tomato sauce… or scraps from the butcher. You take pork rind… put it in a close-up, cut it open with a scalpel, and it looks like human skin.” Garrone points to the film as an authentic historical recreation, only to interchangeably and indifferently describe techniques used to achieve a purely sensational effect. Further historical atrocities have been extensively documented where, for example, mass groups of  prisoners were packed into freight cars where the floors were lined with quicklime.[8] In Gestapo’s Last Orgy, the nude female prisoners are playfully pushed down a makeshift water slide into a pool of quicklime, which merely resembles a harmless white solution. The incompetence of the representations almost begs to be laughed at, yet for anyone who understands the larger context there is no human reaction more unimaginable. As stated by Aaron Barlow, “the DVD has thrown us unprepared into a whole new cinematic possibility where, among other things, the integrity of the film is of higher importance than ever before and its life is immeasurable” (xi). While Barlow’s statement may sound obvious, his use of the term ‘unprepared’ is salient because, when one views this film on the basis of novelty, historical context easily becomes an afterthought. To the producers of Nazi sexploitation films, Levi has stated, “No, the women’s concentration camps are not indispensable to you: you can leave them alone, and not be any the worse off for it” (38), indicating that the use of the camps as a backdrop did not even contribute to the box-office of the films (insofar that the demographic would be indifferent to the historical context). The films’ excesses are thus puzzling in that they seek to be as hideous and reprehensible as possible for no clear or practical reason. Without any motive for this violating and ideologically destructive trajectory, their criminality is not only naïve, but sociopathic, and even nihilistic.

prisoners were packed into freight cars where the floors were lined with quicklime.[8] In Gestapo’s Last Orgy, the nude female prisoners are playfully pushed down a makeshift water slide into a pool of quicklime, which merely resembles a harmless white solution. The incompetence of the representations almost begs to be laughed at, yet for anyone who understands the larger context there is no human reaction more unimaginable. As stated by Aaron Barlow, “the DVD has thrown us unprepared into a whole new cinematic possibility where, among other things, the integrity of the film is of higher importance than ever before and its life is immeasurable” (xi). While Barlow’s statement may sound obvious, his use of the term ‘unprepared’ is salient because, when one views this film on the basis of novelty, historical context easily becomes an afterthought. To the producers of Nazi sexploitation films, Levi has stated, “No, the women’s concentration camps are not indispensable to you: you can leave them alone, and not be any the worse off for it” (38), indicating that the use of the camps as a backdrop did not even contribute to the box-office of the films (insofar that the demographic would be indifferent to the historical context). The films’ excesses are thus puzzling in that they seek to be as hideous and reprehensible as possible for no clear or practical reason. Without any motive for this violating and ideologically destructive trajectory, their criminality is not only naïve, but sociopathic, and even nihilistic.

Central to Bourdieu’s position is a claim that one’s individual tastes are predicated upon cultural capital as it relates to education and social class. Bourdieu considers two relative certainties:

…on one hand, the very close relationship linking cultural practices (or the corresponding opinions) to educational capital (measured by qualifications), and, secondarily, to social origin (measured by father’s occupation); and, on the other hand, the fact that equivalent levels of educational capital, the weight of social origin in the practice-and preference-explaining system increases as one moves away from the most legitimate areas of culture. (13)

I see the entire concept of taste as being uprooted by Nazi sexploitation. By nature of its very title, Gestapo’s Last Orgy was produced and marketed without any consideration whatsoever of taste-on the contrary, the film’s all-out negation of the tasteful is largely the fuel upon which it operates. With a tone of pity, Levi has asserted the demographic for Nazi sexploitation to be “young and old men who are timid, inhibited and frustrated [… who] want the image of an object-woman because they can’t have her in flesh and blood” (38). While the original audience for Nazi sexploitation was clearly heterosexual men, its repackaging has opened the floodgates to a more expansive popular audience whose interest stems from curiosity. Although Levi’s statements with regard to the films’ demographic are relevant, I argue that to place moral judgment on these one-dimensional representations (or those who watch them) only results in the films folding in on themselves. There is nothing productive about simply accusing Nazi sexploitation of being careless, misogynist or historically inaccurate-such statements go without saying, and to consider the films with the hostility that they actively invite is completely counter-productive. While it may sound ridiculous to treat Nazi sexploitation cinema ‘gently’, that is exactly what I propose. To return to my analogy of these films as deviant criminals, I align them with a naïve sensibility insofar that they are too elementary to even comprehend the social and cultural damage that they do. It is as though the proverbial criminal were revealed to only house the intelligence of a child, and would not, as such, be fit to stand trial. Because the films’ representations are so absurd and simplistic, they simply cannot withstand an aggressive academic interrogation, just as a criminal without the intellectual capacity to comprehend his crimes must be evaluated under a different set of criteria.

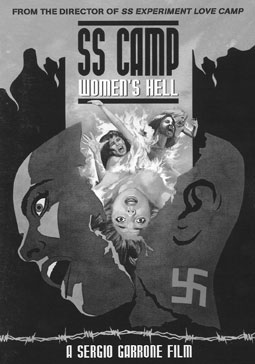

Despite the new ‘elevations’ of these films, there are, nonetheless, socially ordained codes to which even they must adhere. Central to the deviant nature of Nazi sexploitation is its total absence of humour, despite the absurdities of its representations. The informal tone of the plot details, however, on the DVD for SS Experiment Love Camp, makes clear the tongue-in-cheek conditions under which Exploitation Digital has released it. The text reads: “Seems the white race just isn’t superior enough for those nasty Nazis”-indicating, the elaborate packaging notwithstanding, that the film can only be discussed with informal, joking language. The ‘humour’ of Nazi sexploitation is largely derived from how the films do, in  fact, take themselves very seriously.[9] Exploitation Digital, however, protects itself (and its own cultural capital) by phrasing the plot details as it does. Similarly, the DVD for SS Camp Women’s Hell (Sergio Garrone, 1977) states, “[…]this harrowing and tasteless follow-up makes its first (and likely last!) appearance on American DVD” as though the product itself were expressing a genuine surprise at its own existence. In a sense, the marketing of the films needs to clearly indicate that they are not to be taken seriously if they are to be permitted to exist in culture at all.

fact, take themselves very seriously.[9] Exploitation Digital, however, protects itself (and its own cultural capital) by phrasing the plot details as it does. Similarly, the DVD for SS Camp Women’s Hell (Sergio Garrone, 1977) states, “[…]this harrowing and tasteless follow-up makes its first (and likely last!) appearance on American DVD” as though the product itself were expressing a genuine surprise at its own existence. In a sense, the marketing of the films needs to clearly indicate that they are not to be taken seriously if they are to be permitted to exist in culture at all.

Because the films are so cheap and trivial, it may appear that the consumer is simply amused by the inane dialogue or the ridiculous narrative trajectories. What he is laughing at (or perhaps, even being aroused by) is the representation (however inept) of absolutely unspeakable, unquantifiable human suffering. The naïveté of Nazi sexploitation is intrinsic to its own subversive nature. By this, I mean that the films do not understand the enormity of their own historical implications. Despite Levi’s own disgust with the films, he nonetheless retains the objectivity to acknowledge that simply banning them would be to miss the point:

Invoking censorship would mean putting ourselves in the hands of inept and corrupt judges, breathing new life into a dangerous mechanism. We already have censorship, but it confiscates only films that are intelligent, if at times questionable. Obscene films, as long as they are idiotic, present no problem. (38)

Levi’s statement is as salient now as it ever was insofar that the films’ evident incompetence creates the illusion that they are somehow less problematic.

Because Nazi sexploitation exists so far down the scales of cultural capital, it must be able to compromise fidelity to its formal elements (via title changes, alternate cuts) in order to navigate its way through distributional frameworks. Amid the controversy surrounding the release of Caligula (Tinto Brass, Bob Guiccone, 1979), the Magnum label promptly latched Gestapo’s Last Orgy on to the hype and retitled it Caligula Reincarnated as Hitler in its VHS (and later, DVD) release. Just as the film demonstrates indifference to its historical representation, even elements that ‘house’ or contain it (such as its title and box-art) are always negotiable, and the fact that it has no association with Ancient Rome (as depicted, albeit superficially, in Caligula) is of no consequence. Gestapo’s Last Orgy has the unique ability to latch on to any potentially lucrative context because (in a total absence of its own cultural capital) it has nothing to lose.[10] In keeping with the criminality of the films, the restored cut situates Gestapo’s Last Orgy as equivalent to a criminal body whose limbs have, in the wake of being severed, been superficially glued back on in order to celebrate its status as a retro object. As stated by Raiford Guins in his research on the remediation of Italian horror films into contemporary American culture:

It is fair to wager that most Italian horror films to reach American shores as videocassettes were cut to satisfy MPAA censorial policies. This is perhaps the most marked example of Italian horror being positioned as an object of low quality, low value, and further removed from any claim of authorial intentions. In addition to retitling, poor dubbing, and non-‘original’ cover art, it should be stressed that any judgment as to the quality of a particular film was a judgment passed on an incomplete and severely cut print. (21)

What differentiates the Nazi sexploitation cycle from other Italian horror films (such as those of Dario Argento and Mario Bava) is the simple fact that, because quality as such was of no consequence to Nazi sexploitation, there was no ‘artistic legitimacy’ to jeopardize when they were censored. When films such as these are heavily cut, it is easier to protest via a political argument (with regard to freedom of speech) than one defending their artistry. The reassembled cut opens with the statement: “The following presentation of Gestapo’s Last Orgy was completed using multiple sources. We hope the differences in quality do not detract from your enjoyment of this nasty little picture.” Part of the experience of watching the film entails an acknowledgment that it cannot possibly be reassembled perfectly (some of the restored footage comes from deteriorated videotapes with inferior picture quality). After having stagnated in the sewers of culture for decades, the print naturally has some battle scars. I think here of the films as characteristic of a substance with the viscosity of slime – something capable of gluing itself to other forms of culture, and reattaching back to itself, even after it has been severed. This slime has, thus, effectively been cut apart (via censorship and title changes), yet does not suffer artistically when it is excessively edited because it has no artistry to compromise. The films’ slime aesthetic also makes them slippery, able to ooze through the cracks of culture for decades, only to ultimately emerge complete.

Central to Nazi sexploitation is the simple fact that there is absolutely no ambiguity with regard to what these films are; in other words, there is nothing that could possibly be done to a film titled Gestapo’s Last Orgy (or Calgiula Reincarnated as Hitler, for that matter) that could genuinely raise it from the cultural gutters. As I touched on previously, this cinema is so deviant that, not only can it not be elevated, but, as the ultimate cultural deadweight, it actually obliterates the credibility of anything with which it is associated. Consequently, the new and elaborate Exploitation Digital DVD transfer does something that is very  important-it communicates the fundamentally-constructed nature of how ‘high art’ is celebrated, represented, and understood. If a film deemed ‘tasteless’-with a total lack of any cultural capital-can receive a new, clean digital transfer, then it stands to reason that absolutely any film could. While I certainly admire the lush and elaborate digital transfers made available on the Criterion label, when a similar-looking DVD of Gestapo’s Last Orgy is released, a ‘curtain’ of sorts is pulled on the Criterion label (and everything else that purports to represent high art), revealing behind it, a select few whose position it is to pick and choose that which is worthy. It is here that I am reminded of the curtain being pulled on the booming voice in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), only to reveal an ordinary man (Frank Morgan) at the helm of the machinery, influencing innumerable people via illusion. The Nazi sexploitation cycle, in a way unlike any other cinema, pulls the curtain on the inherently constructed and artificial nature of our own hierarchies.

important-it communicates the fundamentally-constructed nature of how ‘high art’ is celebrated, represented, and understood. If a film deemed ‘tasteless’-with a total lack of any cultural capital-can receive a new, clean digital transfer, then it stands to reason that absolutely any film could. While I certainly admire the lush and elaborate digital transfers made available on the Criterion label, when a similar-looking DVD of Gestapo’s Last Orgy is released, a ‘curtain’ of sorts is pulled on the Criterion label (and everything else that purports to represent high art), revealing behind it, a select few whose position it is to pick and choose that which is worthy. It is here that I am reminded of the curtain being pulled on the booming voice in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), only to reveal an ordinary man (Frank Morgan) at the helm of the machinery, influencing innumerable people via illusion. The Nazi sexploitation cycle, in a way unlike any other cinema, pulls the curtain on the inherently constructed and artificial nature of our own hierarchies.

Although I am largely examining how Nazi sexploitation films tear at established institutions, it is important that that not result in a reading of the films as, in any way, progressive. Consider the anxiety of history being forgotten, as expressed by Michel Bouquet in Night and Fog-particularly in the film’s final, incomplete phrase: “…those of us who see the monster as being buried under these ruins, finding hope in finally being rid of this totalitarian disease, pretending to believe it happened but once, in one country, not seeing what goes on around us, not heeding the unending cry-” Bouquet’s statement is salient in that it is simply not acceptable for the discussion of Nazi sexploitation films to end with their being subsumed in a postmodern context as deviant novelty objects. This new packaging alludes to them as somehow being contained, tamed or reconciled by culture. What disturbs me about the re-release of these films as retro products is the impression that we have simply come to terms, not only with our history, but also with the implications of its representation. I have discussed how the films’ re-releases necessitate that they be packaged in such a way that they can be laughed at, but at the same time, I wonder how this laughter could be anything beyond a defense mechanism given that any enjoyment of these films necessarily requires the spectator to ignore what they are really about. Through their ludicrous representation, the films tell their spectator that they are not about anything, and therefore not worthy of further consideration. I propose that there remains an enormous gap between the formal simplicity of the films and the complexity of the cultural discussion that their existence necessitates. Insofar that the mere concept of the Holocaust dwarfs mankind in its scope, the process of packaging these films so as to make them graspable to us is also part of a historical delusion in which the Holocaust itself is made possible to reconcile.[11] These films demand a serious academic interrogation that dares to consider them without judgment, and further acknowledges them, not as trash, but as historical documents in their own right.

As they stand today, Nazi sexploitation films (inadvertently) initiate a dialogue that culture simply does not know how to have. In an effort to reconcile how these films were made and how we must come to terms with them, I borrow a statement from Theodor Adorno, perhaps most famously recognized for his claim regarding the barbarity of writing poetry after Auschwitz:

Guilt reproduces itself in each of us-and what I am saying is addressed to us as subjects-since we cannot remain fully conscious of this connection at every moment of our waking lives. If we […] knew at every moment what has happened and to what concatenations we owe our own existence, and how our existence is interwoven with calamity, even if we have done nothing wrong, simply by having neglected, through fear, to help other people at a crucial moment, for example-a situation very familiar to me from the time of the Third Reich-if one were fully aware of all these things at every moment, one would really be unable to live. One is pushed, as it were, into forgetfulness, which is already a form of guilt. By failing to be aware every moment of what threatens and what has happened, one also contributes to it; one resists it too little; and it can be repeated and reinstated at any moment. (113)

In keeping with Adorno’s claim, the actual medical experiments conducted on camp inmates during the Holocaust represent suffering so disruptive that it is impossible for culture to address head-on and still be left intact. These representations belong exactly where they are-their formal incompetence is necessary, as it is only within the context of nauseated mockery that we can even begin to scratch the surface of what these experiments entailed. Adorno’s assertion that our own social functioning is somewhat predicated on our processes of forgetting is valuable in that it is simply not possible for one to even begin to comprehend the violence inflicted upon the women of the camps and subsequently go on to live one’s own life. Not only do we need these representations, we also need them to be as phony and frivolous as they are-forever on the periphery of cinema, but never completely gone. Culture has thus saddled these films with its own repressed guilt and subsequently expelled them as a scapegoat. It seems here that censors have made effort to persuade themselves of their own civility by banning the films, as though banishing them to the absolute furthest outskirts of the medium would perhaps alleviate a larger social guilt. With the resurgence of these films into the mainstream-marketed as something to laugh at, the repressed has returned in a tangible way. These films represent our own guilt in a state of stagnation-something that we have too long turned away from-and which is, whether we like it or not, a reflection of our own repressions having gone to rot.

Gestapo’s Last Orgy and SS Experiment Love Camp may initially appear unworthy of close analysis. It is however, the influence of our own cultural hierarchies that has enabled them to fly for so long under the academic radar. Any representation designed to elicit such base loathing or appearing to otherwise not be deserving of close consideration, is that which must most urgently be examined. I propose that we discard our cultural hierarchies and examine them as though we would a violent criminal with a childlike understanding of the world. Nazi sexploitation films have demonstrated resilience through past decades, and their recent repackaging has effectively put culture and academia in such a position that it is impossible to continue looking away. From the standpoint of studies in both Film and History, we must, without judgment, closely regard the grotesque representations of Nazi sexploitation because the blood that the films spit back at us is, in a sense, our own.

Notes

[1] Including the notorious Ilsa series, beginning with Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS (Don Edmonds, 1975)

[2] Examples include Yehiel De-Nur’s Holocaust memoir House of Dolls, originally written in Hebrew, alongside Israeli pulp novels referred to as ‘Stalags’.

[3] As reprinted in The Black Hole of Auschwitz (37-8)

[4] These two particular films are frequently considered low-rent remakes/rip offs of Liliana Cavani’s controversial art film The Night Porter (1974).

[5] In 2008, the Danish DVD distributor Another World Entertainment followed suit, releasing the films on Region 2 DVDs in Europe. These releases feature subtitles in Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish, making them accessible to a much wider international audience.

[6] See Isaac Julien’s Badasssss Cinema (2002) and Kristen Hatch’s ‘The Sweeter the Kitten, The Sharper the Claws: Russ Meyer’s Bad Girls’ (145), respectively.

[7] When Medicine Went Mad: Bioethics and the Holocaust (10) features a collection of essays exploring the continued ethical issues faced by medical professionals with regard to experiments conducted during the Holocaust and The Holocaust: Selected Documents in Eighteen Volumes – Vol. 9: Medical Experiments on Jewish Inmates in Concentration Camps features extensive reproductions of original documents.

[8] See, for example, Robert M. Spector’s World Without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust, History and Analysis: Vol. I (435).

[9] The lead actors of Gestapo’s Last Orgy assumed pseudonyms for their roles (Adriano Micantoni is credited as Marc Loud and Daniela Poggi, as Daniela Levy). Similarly, Bruno Mattei directed SS Girls under the name Jordan B. Matthews.

[10] The film, further, opens with a quote from Nietzche in reference to his Übermensch (Superman) that is not only out of context, but misspells his name (without the ‘t’). Similarly, Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS opens with a quotation from Thomas Jefferson.

[11] ‘High art’ Hollywood melodramas such as Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg, 1993) are equally applicable to such an argument.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. Metaphysics: Concepts and Problems. Ed. Rolf Tiedemann. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique on the Judgement of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1984.

Guins, Raiford. “Blood and Black Gloves on Shiny Discs: New Media, Old Tastes, and the Remediation of Italian Horror Films in the United States.” Horror International. Eds. Steven Jay Schneider, Tony Williams. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2005. 15-32.

Hatch, Kristen. “The Sweeter the Kitten the Sharper the Claws: Russ Meyer’s Bad Girls.” Bad: Infamy, Darkness, Evil, and Slime On Screen. Ed. Murray Pomerance. Albany: State U of New York Press. 2004, 142-55.

Levi, Primo. The Black Hole of Auschwitz. Ed. Marco Belpoliti. Trans. Sharon Wood. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

Spector, Robert M. World Without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust, History and Analysis: Vol. I. Lanham: UP of America, 2005.

This text is the most astonishingly consequent and hostile manifestation of scholarly bigotry within the reception of exploitation cinema I have ever come across on the net. Congratulations, it impressed me profoundly. I always thought that us Germans already were busy enough (obssessively busy, in fact) with handling our past and that our being busy was so (Germanly) thorough that no other country would need to worry about our past being mistreated or even forgotten. It’s rather refreshing to see that I was wrong.

What a pitifully narrow-minded approach to the toppic. How about an essay about SCHINDLER’S LIST, THE READER and similar films, viewing them as Nazi exploitation (or even PORNOGRAPHY) as well? What did he write about the exclusively commercial aim of Nazi exploitation again?

I guess this comment will not be released as it has to be a forerunner of new fascist leanings in Germany which might have been caused by secret screenings of Italian Naziploitation films.

I nearly forgot this:

“I base my position on what I see as a general consensus of the artistic legitimacy (or ‘cultural capital’) of Nazi sexploitation being non-existent.”

If the author actually did that (which I have every reason to believe, judging from the rest of the text), he based his position on a consensus which itself is based on a genuinely fascist ideal – the ideal of separating the artistic and the trivial from each other. The more I think about it, the more I’m repelled by this article which even fails to produce any arguments apart from “Such as my shock about the utter tastelessness and perversity of these films that I decided they should all be burned” [just like the books of Bertolt Brecht and Erich Kästner during the 3rd Reich]

Nazi Sexploitation plays into the very real process by which the Nazis would dehumanize Jewish and non-Jewish concentration camp inmates. First by stripping them naked, to the supposed ends of issuing new uniforms shaving off both head hair and intimate hair. But often it was days before the new uniforms were issued and men women, children and maturing teens would be lumped together covering their bodies only with their hands while hanging their heads and whimpering from shame.

Of course, in Sexploitation movies, the nudes are all female, 18-34 years of age and suspiciously well-fed and coiffed. Sadly in few of these films do the naked “inmates” make any effort to cover their nudity. I think it’s great sport to watch a freshly-stripped female inmate try cover a DD bust with one hand and arm with the other shields her genitals but not all of her schamhaar, or”pubes”.

Long before the Nazi practice of making prisoners go around naked, the Germans made a direct connection between pubic hair especially the female triangle and the shame of its forced exposure.

Lucky for the female concentration camp inmates, their schamhaar was shorn clean presenting their virtually prepubescent vulvae to all who cared to see. One thing I noticed from TIME/Life WW-2 volumes is that Eastern-European Jewish women were typically of very matronly builds who largely served their communities through reproductive means and had bred out petite figures for massive breasts and hips. Forced to go nude, They would often be so self-conscious of their breasts, they’d leave their crotches exposed but hug their upper bodies with both arms, resulting in very enticing cleavage.

One Nazi SS camp official, instructed that sexual congress with a Jewish woman amounted to “bestiality”, repeatedly denied any sexual gratification from slapping and smacking only the largest of Jewish breasts. “I do it to remind the untermensch that they are as cattle.I I randomly strip-search our workers for smuggled materials. After they have all undressed I will announce that I require the woman with the biggest breasts to stand forward. They look at one another and wordlessly the one who must acknowledge her advantage over the others. I then drum on those tits like timpani to Herr Wagner’s ‘Ride Of The Valkyrie’. By the end of my performance, they are slippery with tears.” The women would stand helplessly naked and weep over their own manhandled bosoms.

I’ve never seen THAT in a movie.

I have watched many such films from this era and must say that the “minimalization” that is perpetrated by these productions is aimed at the Germans themselves, and not the labour camp victims per se. The actresses in particular almost always have German features and blonde hair (whether they be victims or camp officials) and if anything, an element of obfuscation is used to blur the lines between sexuality and depravity. All of these movies have only furthered the hyper-sexualization of Europeans during the post war period which has effectively neutered the once healthy sex drives of Europeans in general. And this was by design when we look at the persons who were involved in their production…

R>