Andrew deWaard

It ain’t nothin like the shit you saw on TV.

Palm trees and blonde bitches?

I’d advise to you to pack your shit and get the fuck on;

punk motherfucker!

– Ice Cube, “How to Survive in South Central”

Recuperating the term melodrama within film studies has become quite the melodramatic project unto itself. Scorned and disdained, this suffering victim has been the object of much derision, particularly in its latest incarnation in popular American mass culture. Vulgar, naïve, sensational, feminine, sentimental, excessive, overly emotional – these are but a few of the disparaging descriptions that have robbed melodrama of its ‘virtue.’ However, in true melodramatic form, its virtue has been restored in recent years with heightened and sensational gestures by such ‘noble heroes’ as Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. Not content with simply defending its honour, Williams claims that “Melodrama is the fundamental mode of popular American moving pictures” (1998: 42), and “should be viewed… as what most typifies popular American narrative in literature, stage, film and television” (2001: 11). But like any good melodrama worth its weight in tear-soaked hankies, the melodrama of melodrama’s recuperation does not have a clear-cut happy ending – there is still much work to be done.

Drawing heavily from Peter Brooks’ seminal 1976 book, The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess, the work of Gledhill and Williams opens up a new avenue for the study of cinematic melodrama. Rather than its typical – albeit contentious – configuration as a genre, melodrama can also be viewed as a mode: melodrama’s “aesthetic, cultural, and ideological features [have] coalesce[d] into a modality which organizes the disparate sensory phenomena, experiences, and contradictions of a newly emerging secular and atomizing society in visceral, affective and morally explanatory terms” (Gledhill 2000: 228). If melodrama is to be understood as a continually evolving mode, “adaptable across a range of genres, across decades, and across national cultures” (229), then its progress needs to be continually charted, its latest forms constantly delineated. Unfortunately, much of the scholarship concerning melodrama is still preoccupied with either reclaiming past works, rarely moving beyond the classical Hollywood era, or focused on specific auteurs, from D.W. Griffith to Douglas Sirk to contemporary directors such as Pedro Almodóvar and Todd Haynes. As “a tremendously protean, evolving, and modernizing form that continually uncovers new realistic material for its melodramatic project” (Williams 2001: 297), only after significant scholarship that considers its various contemporary forms will melodrama’s dominance as a fundamental mode be widely received and accepted.

As part of that project, my aim is two-fold: map the melodramatic mode onto a previously unconsidered genre – the ‘hood film cycle of the early 1990s – and then analyze the impact of what amounts to be the melodrama of the map. Plotting the melodramatic mode onto such a disparate and seemingly incompatible genre such as the ‘hood film should explicate the geography of the melodramatic mode, showcasing its fundamental characteristics and concerns. Witnessing its application in such a violent and ‘masculine’ genre as the ‘hood film should also prove the versatility of the melodramatic mode. Following this structuralist task, this new melodramatic incarnation will be explored in terms of its evolution of the melodramatic mode, demonstrating melodrama’s capability of constant reinvention. With the ‘hood film, a key shift occurs: the home – a crucial concern in melodrama – becomes the ‘hood, and it requires fleeing. Intimately connected to this disfigured sense of space is that other, often overlooked concern of melodrama: the melos. Music in the ‘hood film is of central importance in stressing the spatial and temporal logic of the ‘hood. With the ‘hood film, melodrama is put in service of a much larger than normal concern: the crisis in the African American urban community.

The Geography of Melodrama: Pathos N the ‘Hood

Express yourself / From the heart,

Cause if you wanna start to move up the chart,

Then expression is a big part.

– Dr. Dre (of N.W.A.), “Express Yourself”

The ‘hood film demarcation refers to a series of African American films released in the early 1990s, identified by a strong connection to youth rap/hip hop culture (via soundtrack and rappers-turned-actors), contemporary urban settings (primarily black communities in Los Angeles or New York), and inner-city social and political issues such as poverty, crime, racism, drugs, and violence. The ‘hood film genre’s most renowned and successful films, as well as its most representative, are Boyz N the Hood (John Singleton 1991) and Menace II Society (Allen and Albert Hughes 1993). Spike Lee, while transcending the confines of the ‘hood film genre, is a significant figure in the development of African American filmmaking at this time. His classic Do the Right Thing (1989) can be seen as the ‘hood film’s precursor, while Crooklyn (1994) and Clockers (1995) prominently feature his hometown of Brooklyn. Other examples of the ‘hood film include New Jack City (Mario Van Peebles 1991), Straight Out of Brooklyn (Matty Rich 1991), Juice (Ernest Dickerson 1992), Just Another Girl on the IRT (Leslie Harris 1992), Deep Cover (Bill Duke 1992), and “over twenty similarly packaged feature-length films between 1991 and 1995” (Watkins 172).

The ‘hood film quickly gained notoriety in the early 1990s as a result of the vast media attention these films garnered from their surprising financial success and headline-grabbing violence at some theatrical exhibitions. This output of ‘hood films did not last long, but it marked the first major wave of African American film production since the Blaxploitation era. “Production in 1990 and 1991 alone,” according to Ed Guerrero, “easily surpassed the total production of all black-focused films released since the retreat of the Blaxploitation wave in the mid-1970s” (155). Consequently, critics of African-American film were quick to explore and interpret this unique set of films, collecting them under a variety of labels other than just the ‘hood moniker: “New Jack Cinema” (Kendall), “black action films” (Chan), “male-focused, ‘ghettocentric,’ action-crime-adventure” films (Guerrero 182), “trendy ‘gangsta rap’ films” (Reid 457), and “the new Black realism films” (Diawara 24). In all of these considerations of genre, the word melodrama rarely appears; if it does, it is in its typical derogatory usage. This is a tremendous oversight; the ‘hood film’s fundamental core is the melodramatic mode.

Considered by Williams to be “perhaps the most important single work contributing to the rehabilitation of the term melodrama as a cultural form” (1998: 51), Brooks’ The Melodramatic Imagination traces the historical origins of the form, applies his findings to the work of Balzac and Henry James, and establishes melodrama as a significant modern mode in the process. Situated as a response to the post-Enlightenment, post-sacred world that arose out of the French Revolution, “melodrama becomes the principal mode for uncovering, demonstrating, and making operative the essential moral universe in a post-sacred universe” (Brooks 15). With the traditional imperatives of truth and ethics thrown into question, melodrama was to express what Brooks calls the “‘moral occult,’ the domain of operative spiritual values which is both indicated within and masked by the surface of reality” (5).

Brooks’ isolated concern with the nineteenth-century realist novel, particularly Balzac and James, proves to be both an asset and a hindrance to the theory of melodrama. Brooks is able to earnestly re-evaluate the form without the trappings of ideological condescension, allowing him to highlight its core characteristics, but he fails to trace its importance in popular culture, where it has continually evolved. Considering its modern reinvention, Gledhill and Williams break with Brooks in his view of melodrama as being in opposition to realism and as a mode of ‘excess.’ In Gledhill’s consideration, contemporary forms of melodrama are firmly grounded in realism: “Taking its stand in the material world of everyday reality and lived experience, and acknowledging the limitations of the conventions of language and representation, it proceeds to force into aesthetic presence identity, value and plenitude of meaning” (1987: 33). Williams goes a step further, suggesting that the term ‘excess’ be eliminated from melodramatic discourse all together: “The supposed excess is much more often the mainstream, though it is often not acknowledged as such because melodrama consistently decks itself out in the trappings of realism and the modern (and now, the postmodern)” (1998: 58). As melodrama has developed, it has cloaked itself in ‘realism’ but remained fundamentally concerned with revealing moral legibility.

For all her rhetoric concerning melodrama being the primary mode of contemporary American mass culture, Williams’ examples do not quite do her thesis justice. “Melodrama Revised” focuses on D.W. Griffith’s Way Down East (1920), only briefly contemplating Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg 1993) and Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme 1993), as well as some select Vietnam films, while Playing the Race Card only goes as far as the Roots miniseries, moving to ‘cultural event’ with the Rodney King and O.J. Simpson trials as her most contemporary consideration. The ‘hood film will prove a convincing illustration of contemporary melodrama grounded in everyday reality with an effort towards realism. We can structurally outline the melodramatic ‘hood film via Williams’ five-point systematic breakdown of the melodramatic mode:

1. “Melodrama begins, and wants to end,” according to Williams, “in a space of innocence” (1998: 65), usually represented by the iconic image of the home. Immediately, the ‘hood film puts a spin on this most central of melodramatic concerns, adhering and deviating from convention right from the start. As will be considered in more depth in the second part of this essay, the home has become the community at large – the ‘hood – and it is portrayed as an area of crisis, so it is not presented as a space of innocence. However, the use of children in this space does express the innocence and virtue from which melodrama typically originates. Spike Lee often celebrates his Brooklyn community with loving tributes to the way children manage to create fun out of minimal resources and confined spaces, such as the opening montage of various street activities – jump rope, hopscotch, foot races, street baseball, etc. – in Crooklyn, and the jubilant fire hydrant scene in Do the Right Thing.

Many ‘hood films take the form of coming-of-age tales, charting a path of lost innocence as the corrupting influence of the ‘hood takes its toll on the film’s young protagonists. Juice follows four teenagers navigating the treacheries of the ‘hood, while both Boyz and Menace II Society track children growing up across many years in the ‘hood, featuring extended introductory scenes of the trauma faced by prepubescent inhabitants of the ‘hood. In Boyz, the story begins with four school children walking down a dilapidated, garbage-laden street, discussing their homework in the same breath as the previous night’s shooting. Exploring a crime scene, one child is rebuked for not recognizing bullet holes; she responds by proclaiming that at least she knows her times-tables. The subsequent shot is a slow pan across a classroom wall, showcasing the children’s endearingly simplistic art depicting police cars, helicopters conducting surveillance and family members in coffins – a striking juxtaposition of innocence and affliction.

2. “Melodrama focuses on victim-heroes and the recognition of their virtue” (1998: 66). The ‘hood film’s usage of victim-heroes is comparable to Thomas Elsaesser’s position on 1950s family melodrama which “present all the characters convincingly as victims” (86). Characters in ‘hood films are (almost) all compelling victims because of the dire depiction of their surroundings. Poverty, crime, drugs, racism, and violence – everyone is a victim. Even disagreeable characters are viewed as victims on account of this situation. Boyz‘s Doughboy (Ice Cube), for instance, is a violent, misogynistic drug dealer, but he attains sympathy on account of the troubled relationship he has with his mother, a single mom struggling to provide for her two sons, privileging one over the other. Doughboy is also given the film’s key piece of dialogue in its concluding scene, both incendiary critique and induction of pathos: “Either they don’t know, or don’t show, or don’t care about what’s going on in the ‘hood.” As victims of the ‘hood, suffering is felt by one and all.

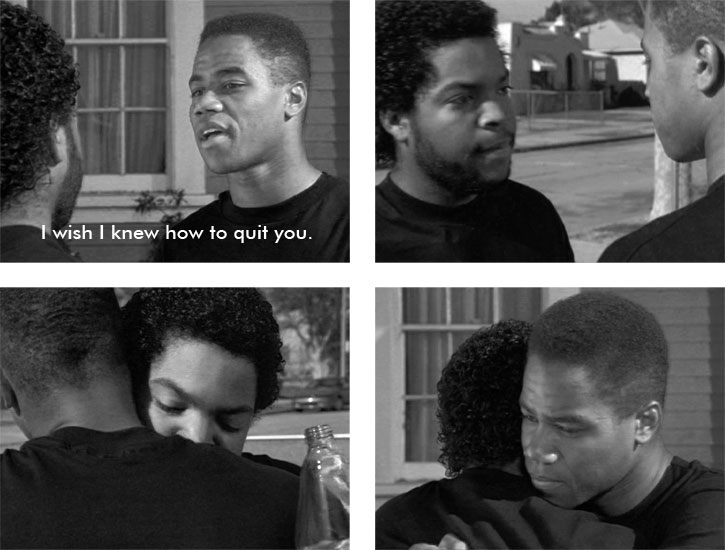

Emotionalism is key in recognizing the virtue of the victim-hero, and it is highly visible in the ‘hood film, despite its rough exterior of tough language and gritty violence. In Boyz, for instance, following an unjust encounter with the police, Tre returns to his girlfriend Brandi’s (Nia Long) house and proceeds to have an emotional breakdown. Swinging his fists wildly in the air before falling into Brandi’s arms, Tre acts out his frustration and demonstrates his vulnerability, “a pivotal moment” according to Michael Eric Dyson, “in the development of a politics of alternative black masculinity that prizes the strength of surrender and cherishes the embrace of a healing tenderness” (135).

In ‘hood films that primarily revolve around one central character – Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.) in Boyz, Caine (Tyrin Turner) in Menace, Mookie (Spike Lee) in Do the Right Thing – the victim-hero is always torn between allegiances to his fellow victims in the ‘hood and the opportunity for upward mobility. As “the key function of victimization is to orchestrate the moral legibility crucial to the mode,” (Williams 1998: 66) the victim-hero of the ‘hood film always has their virtue recognized in the conclusion of the film as testament to the conditions of the ‘hood. Whether by refusing to participate in the cycle of black-on-black violence (Boyz), shielding a child from a drive-by shooting (Menace), or inciting a riot in response to a savage murder by a policeman (Do the Right Thing), the victim-hero makes a moral stand in opposition to the injustice perpetrated against the ‘hood.

3. “Melodrama appears modern by borrowing from realism, but realism serves the melodramatic passion and action” (1998: 67). While conventional wisdom posits melodrama as a crude retrograde form out of which a more modern realism developed, upon considering contemporary melodrama it becomes clear that realism is in fact at the service of the traditional melodramatic mode, albeit in a disguised, modernized fashion. The second part of this essay will explore the way the ‘hood film is rooted in a realist portrayal of a specific spatial and temporal existence, but we can briefly look at Menace as an example of the way realism is used in the service of melodrama in the ‘hood film.

Explicitly foregrounding its story amidst a history of racial violence, Menace uses pixelated archival footage of the 1965 Watts riots immediately following its opening scene. This imagery would most certainly have resonated with audiences at the time, as the Los Angeles riots that occurred in response to the acquittal of Rodney King’s assailants happened the previous year. Our introduction to the current state of Watts is perceived in a bird’s-eye view long shot, “in an almost ethnographic manner, with an invasive camera looking down on and documenting the neighbourhood” (Massood 165). A testament to the film’s tagline, “this is the truth, this is what’s real,” Menace is quick to establish its ‘realistic’ backdrop before delving into its otherwise typically melodramatic portrayal of a victim-hero’s eventual recognition of virtue.

4. “Melodrama involves a dialectic of pathos and action – a give and take of ‘too late’ and ‘in the nick of time'” (1998: 69). Williams makes a key insight into the melodramatic mode when she connects pathos to action, permitting the most seemingly unmelodramatic of films to be viewed in a new light. In its elucidation of a character’s virtue in the climax, melodrama tends to end in one of two ways: “either it can consist of a paroxysm of pathos… or it can take that paroxysm and channel it into the more virile and action-centered variants of rescue, chase, and fight (as in the western and all the action genres)” (1998: 58). Boyz provides a tremendous example of this transition between pathos and action, complete with all the requisite ingredients. The virtuous ‘good son’, Ricky (Morris Chestnut) is mistakenly caught up in a turf war, and Tre’s warning calls are ‘too late’ to save him from a drive-by shooting, as is Doughboy’s rescue attempt. The chase and fight to revenge this innocent’s death is triggered, while the pathos is increased by the letter indicating Ricky’s successful completion of the SATs, his ticket out of the ‘hood, waiting in the mail all the while.

Paradoxically, Albert and Allen Hughes claim that the impetus for creating Menace was being “outraged by the Hollywood sentimentality” (Taubin 17) of Boyz, and their desire to capture what they considered was the ‘real’ situation in the hood. But upon consideration of its similar use of the melodramatic mode, there is very little difference between the climax of each film. True, Caine dies in Menace, as opposed to Tre’s escape in Boyz, but the recognition of virtue in a dialectic of pathos and action is equally as strong in the climax of Menace. Moreover, by threatening the death of a child, the Hughes Brothers are even more guilty of ‘Hollywood sentimentality.’

Like Ricky’s death in Boyz, the climax of Menace plays on the qualities of ‘too late’ and ‘in the nick of time.’ Crosscutting between the final stages of Caine and Ronnie’s (Jada Pinkett) packing up of their life, just about to escape the ‘hood, and the oncoming evil in the form of a drive-by shooting, the scene is an example of melodramatic temporal and rhythmic relations: “we are moved in both directions at once in a contradictory hurry-up and slowdown” (Williams 1998: 73). The car approaches in slow-motion, while Caine and his friends unknowingly laugh and fraternize in real-time. The action feels fast, but the duration of the event is actually slowed down, and the outcome of whether or not the child is also killed is delayed. Evoking the melodramatic motif of tableaux, a final montage of images from Caine’s life in the ‘hood – violence, laughter, a police arrest, a tear in prison, a tender kiss, teaching a child – are intercut with quick fades to black, Caine’s redemptive voice-over, and the sound of Caine’s slowly fading heartbeat. Punctuated by a final jarring gunshot, this scene of intense action is in the service of significant pathos for its virtuous victim-hero.

5. “Melodrama presents characters who embody primary psychic roles organized in Manichaean conflicts between good and evil” (1998: 77). The most derided characteristic of melodrama, the lack of complex psychological depth common to melodrama is an objectionable quality, but there is no denying its prevalence in mass culture. Vilifying perceived evil is frequent and widespread, often in service of a separate agenda, but the ‘hood film contains an example, from a certain viewpoint, of ‘deserved’ vilification on behalf of the mistreated and oppressed. While most characters in the ‘hood are seen as victims of their surroundings, there is one individual that is unanimously disdained in the ‘hood film: the policeman.

From Michael Stewart to Eleanor Bumpers to Rodney King to Amadou Diallo, there is a long history of police brutality upon innocent African Americans with no justice brought upon the perpetrators. Do the Right Thing was released in the midst of a series of racially motivated crimes perpetrated by New York City policemen. A few of these cases are explicitly mentioned in the film, as characters yell out “Michael Stewart”, “Eleanor Bumpers”, and “Howard Beach” during the riot scene. The credit sequence also pays respect and dedicates the film to the families of six recent victims of police brutality. Michael Stewart is of particular importance to this film, as Radio Raheem’s (Bill Nunn) death is a direct mirroring of Stewart’s attack. In 1983, Michael Stewart, a 25 year-old black man, was arrested for scribbling graffiti and was subsequently choked to death by 3 officers who were eventually acquitted of any wrongdoing. The exact same scene is re-enacted in Do the Right Thing, an example of what is referred to as the ‘Michael Stewart Chokehold’. The police are perceived similarly in other ‘hood films, but we will return to their depiction when we consider their effect on spatial logic. With the melodramatic mode of the ‘hood film sufficiently mapped, we can now turn to the melodrama of the map.

The Melodrama of Geography: The ‘Hood is Where the Heart Is

A fucked up childhood is why the way I am;

It’s got me in the state where I don’t give a damn.

Somebody help me, but nah they don’t hear me though,

I guess I’ll be another victim of the ghetto.

– MC Eiht, “Str8 Up Menace”

The ‘hood film clearly operates on the principles of the melodramatic mode, but as a narrowly defined genre with specific concerns, it is of particular interest to note how the ‘hood film uses melodrama for its own spatial problems. This entails the modification of two of the most central concerns of melodrama – the home and the melos – in a decidedly uncharacteristic manner. The home has typically been the “space of innocence” (Brooks 29) in melodrama, but as the home is portrayed as just one of the many afflicted and deprived spaces in the ‘hood film, the central place of concern becomes the ‘hood as a whole. Although there are central characters with which to follow the narrative, a multitude of characters and relationships are presented in order to attempt a full portrait of the community. Apart from Crooklyn, private spaces in the home are viewed very rarely; instead, much of the action takes place on the streets and throughout the neighbourhood: “It is the primacy of this spatial logic, locating black urban youth experience within an environment of continual proximate danger that largely defines the ‘hood film” (Forman 258). The main focus of the ‘hood film becomes the power relations inherent in space, where race determines place; this is a story of the melodrama of geography.

Paula J. Massood’s Black City Cinema provides a useful approach to analyzing the ‘hood film, as she utilizes Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope to explore the way African American film is often preoccupied with the urban cityscape. A topos (place or person) that embodies or is embodied by chronos (time), Bakhtin’s chronotope is a model for exploring temporal and spatial categories embodied within a text. The chronotope views spatial constructs as “‘materialized history,’ where temporal relationships are literalized by the objects, spaces, or persons with which they intersect” (Massood 4). In Massood’s judgment, the chronotope is of particular relevance to African American filmmaking, as its main historical moments are often concerned with the contemporary city, from Oscar Micheaux’s connection to the Harlem Renaissance to blaxploitation’s use of the sprawling black ghetto in Los Angeles and New York City. The ‘hood film would redefine black cinematic space with what Massood refers to as the ‘hood chronotope.

A strong sense of ‘here and now’ pervades the ‘hood chronotope. All of the narratives in the ‘hood film genre take place in confined geographic coordinates – South Central Los Angeles, Watts, Brooklyn, or Harlem – and are all filmed on location. They are almost all clearly marked to be diegetically taking place at the extradiegetic time of the film’s release as well. Corresponding to the coming-of-age trope, the ‘hood functions as the space where right now, young African Americans are struggling to grow up in bleak conditions. According to Massood, Boyz “literally mapped out the terrain of the contemporary black city for white, mainstream audiences” (153). An important impetus for the creation of this ‘hood chronotope is to shed light on a mostly unseen geographic space in mainstream media.

It is fitting that Boyz and Menace are both set in Los Angeles, a city that notoriously manufactures its reality through fantasy, primarily via Hollywood’s spectacular imagery. Creating a self-image of abundance and sunny paradise, L.A. privileges its prosperous areas – Beverly Hills, Hollywood, Bel-Air, Malibu – while excluding its ‘other’ spaces from representation. Boyz and Menace construct an image of Los Angeles overrun with poverty, violence, drugs, and racism – “a likeness that stands in contradistinction to the tropical paradise manufactured both by the city’s boosters and by the movie industry” (Massood 148). In this way, the films are self-reflexive discourses about the dynamics of power inherent in representation and image manufacture. Along with rap music and footage of the Rodney King beating and the subsequent riot, the ‘hood film exposes the ‘two-ness’ of African-American identification, both inside and outside the ‘American’ experience.

On the other hand, the ‘hood film is also concerned with remedying an outsider (read: white) examination of the ‘hood. South Central Los Angeles had only received cursory treatment in the American social imagination up until the ‘hood film, but what was represented was crude and sensationalistic. A highly publicized 1988 TV special by Tom Brokaw and Dennis Hopper’s film Colors (1988) both concentrated solely on gang warfare, failing to provide any substantial context for the catastrophic environments presented. “Singleton’s task [with Boyz] in part,” according to Michael Eric Dyson, “is a filmic demythologization of the reigning tropes, images, and metaphors that have expressed the experience of life in South Central Los Angeles” (125). The melodramatic mode is crucial here in presenting a diverse range of sympathetic characters and relationships that complicate the previously unsophisticated view of the ‘hood. Thus, the ‘hood film bears a heavy burden of representation; it must portray the ugly realities of a Los Angeles rarely seen, but not fall into the sensationalistic, one-dimensional depictions which it is attempting to correct.

One of the ways the ‘hood film navigates this tenuous representation is to present the city as a bounded civic space made up of contained communities. The feelings of enclosure and entrapment become palpable in the ‘hood film, and a system of signs is encoded in the terrain to make this atmosphere explicit. The first frame of Boyz has the camera dramatically tracking in on a stop sign, filling the screen with the word “STOP” while a plane flies overhead. Signaling both the desire for mobility and the institutional limits that prevent such movement, this sign is just the first in a series of “One Way” and “Do Not Enter” signs that pervade the urban environment of the film, controlling movement and preventing free passage. Menace exhibits a similar system of signs. Prior to Caine being shot and his cousin fatally wounded, a sign for Crenshaw Boulevard is shown while a streetlight turns red, again suggesting the limitations of movement within the ‘hood.

On the other side of the country, entrapment and enclosure takes on a different materialization. As opposed to the horizontal ‘hood of South Central Los Angeles, the ‘hood in Straight Out of Brooklyn, Juice, and Clockers is a vertical construction, set among New York’s high-rise housing projects and adjacent neighbourhoods. Constraint and restricted mobility is evidenced here by visual tightness and spatial compression, fueling the stress and tension of the narrative. Rather than street signs, buildings and brick exteriors become the visual motif of “a world of architectural height and institutional might that by contrast diminishes their own stature as black teenagers in the city” (Forman 270). Unlike the spatial expanse of South Central Los Angeles, the ‘hood in New York is a maze of constricting and connecting contours, violence and death awaiting around every corner.

Common to ‘hoods on both the East and West coast, however, is the ominous presence of the police. In Boyz, the recurring appearance of two patrolmen, the more abusive of the two being black, again indicates a strong institutional constraint on mobility. A multitude of aural and visual cues also speaks to this ubiquity of police surveillance, particularly the persistent searchlights and off-screen sounds of police helicopters. Invoking Foucault’s panopticon, Massood claims that “this method of control, dispersed over the urbanscape, facilitates efforts to keep the community in its place through the internalization of surveillance and the consciousness of perceived criminality” (156). Scenes in both Boyz and Menace show the boys being stopped and harassed by the police for simply driving in the wrong place at the wrong time, reinforcing this idea of perceived criminality based on geography.

Another integral element in this spatial configuration of the ‘hood is the strong connection to rap and hip hop culture. In fact, it was the song “Boyz-N-the-Hood” by Easy-E in 1986 that first established “the ‘hood” as an important term in the spatial discourse of young urban blacks across the country. West Coast gangster rap, particularly N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton in 1989, “vividly portrays the ‘hood as a space of violence and confrontation, a zone of indiscriminate aggression where threat and danger are commonplace, even banal” (Forman 263-4). Both intimately concerned with spatial logic, sharing narrative and visual imagery, hip hop and the ‘hood film demonstrate a bond of cross-pollination and reciprocal influence. The casting of Ice Cube in Boyz, MC Eiht and Pooh Man in Menace, Ice T in New Jack City, and Tupac Shakur in Juice contributes to each film’s credibility and authenticity among young audiences, while at the same time providing enhanced exposure for the hip hop artists, all of whom contribute to the films’ soundtracks. Dyson partially attributes this coalescence to the problems of the ‘hood, whereby “young black males have responded in the last decade primarily in a rapidly flourishing independent popular culture, dominated by two genres: rap music and black film… [where they can] visualize and verbalize their perspectives on a range of social, personal, and cultural issues” (124). As a result, the use of rap music is a textual and paratextual modernization of the melodramatic mode.

Not only does the use of rap music contribute to the ‘hood film’s specificity of place, but also its specificity of temporality. In Boyz, for instance, the scenes of Tre’s childhood are accompanied by nondiegetic jazz-based, ambient music, but when the narrative is propelled into the present, to the same year as the film’s release, rap music signifies and solidifies this shift. In addition, the ‘hood film’s use of urban dialogue and clothing (think of Spike Lee’s fixation with basketball sneakers and sports jerseys) complement the sound of urban experience with its look. Placing the narrative in a specific time and place, providing it with cultural currency, rap music – and its accompanying urban referents – is essential to the portrayal of the ‘hood chronotope.

As indicated in its literal meaning, “drama accompanied by music,” melodrama is fundamentally tied to its use of music to emphasize and underscore its pivotal moments. Rap music is used in just such a fashion, but it also incorporates another melodramatic trope: the lower classes. As its historical emergence among the poor in the French Revolution indicates, “melodrama sides with the powerless” (Vicinus 130). Rap music similarly arose out of lower class conditions – the Bronx in New York City – and along with its spatial and temporal priorities, provides a perfect complement to the melodrama of the ‘hood film. Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” commissioned specifically for Do the Right Thing, acts as a diegetic soundtrack within the film, the physical catalyst for the film’s violent conflict, and a rallying call against the injustice faced in the ‘hood. The ‘hood film puts the melos back in melodrama.

All these elements that contribute to the spatial and temporal logic of the ‘hood build to the central dilemma of many ‘hood films: should the ‘hood be abandoned? This is a twist on the typical melodramatic trajectory; whereas the home is traditionally the space of innocence to be restored in melodrama, the ‘hood – in the place of the home – is seen as beyond rescue in the ‘hood film. Boyz, Menace, and Clockers problematically advocate fleeing the ‘hood as the only means of survival and advancement. Paradoxically, with the privileging of the father in Boyz (also problematic), Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne) instills Tre with the ethical responsibility desperately needed in the ‘hood, but it instead equips him with the mobility to leave the ‘hood for college in Atlanta. Similarly, Menace also suggests leaving the ‘hood as the only means of escaping the cycle of violence and crime, although Caine does suggest Atlanta is just another ghetto where they will remain victims of institutional racism. To those who cannot escape the ‘hood, or cannot escape in time, death awaits.

On the surface, we can take issue with such a seemingly contradictory resolution. If the ‘hood film works so hard to communicate the problems facing this community, why would it advocate its abandonment? This false dilemma seemingly

reinforces the conservatives’ one-sided picture of personal responsibility and choice, conceals the racist underpinnings of spatial containment, and deflects attention from the need of governmental and social agencies to financially and logistically support and assist black inner-city districts in urban renewal and social healing (Chan 46).

While a critique such as Chan’s against the ‘hood film’s abandonment of its own concern is certainly valid, I think viewing the dilemma from the perspective of its melodramatic mode presents another story. This logic of “flee the hood or die” is typical of the melodramatic “logic of the excluded middle” (Brooks 15), in which dilemmas are posed in Manichaean terms. By framing the protagonist’s predicament as a do-or-die scenario, the opportunity is created for the pathos-through-action climaxes discussed previously. As a result, the victim-hero earns sympathy and the moral good is revealed, inviting the viewer to be moved by the victim’s dire circumstances, in this case, the detrimental conditions of the ‘hood.

Furthermore, as Laura Mulvey states, “the strength of the melodramatic form lies in the amount of dust the story raises along the road, a cloud of over-determined irreconcilables which put up a resistance to being neatly settled in the last five minutes” (76). Even if the conclusion of Boyz was a big Hollywood wedding between Tre and Brandi, it would not erase the previous 90 minutes of turmoil. In this sense, the contention over the abandonment of the ‘hood, and the difference between the endings of Boyz and Menace, is rendered moot on account of the melodramatic actualization of the ‘hood. There are certainly other problematic features of the ‘hood film as well – its glorification of violence, its troubled gender roles – but its overarching melodrama is of an ultimately racist spatial construction of the ‘hood, where physical and psychological barriers are erected that confine an underclass to a segregated space. This overarching problem is not lost to whatever narrative or thematic inconsistencies one may find.

Williams claims that “critics and historians of moving images have often been blind to the forest of melodrama because of their attention to the trees of genre” (1998: 60). Part one of this essay aims to have remedied that mistake concerning the ‘hood genre and its overlooked melodramatic foundation. Furthermore, despite whatever problems with the ‘hood film we may find, we would be wise to not be distracted by the trees of its problematizations; instead, we should focus on the forest of the hood’s spatial melodrama.

Works Cited

Brooks, Peter. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Chan, Kenneth. “The construction of Black Male Identity in Black Action Films of the Nineties.” Cinema Journal. Vol. 37, No. 2. Winter 1998.

Diawara, Manthia. “Black American Cinema: The New Realism.” Black American Cinema: Aesthetics and Spectatorship. Ed. Manthia Diawara. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Dyson, Michael Eric. “Between Apocalypse and Redemption: John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood.” Cultural Critique. No. 21. Spring 1992.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Tales of sound and fury: observations on the family melodrama.” Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film. London: BFI Pub, 1987.

Forman, Murray. The ‘hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip-Hop. Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press, 2002.

Gledhill, Christine. “Rethinking Genre.” Reinventing Film Studies. Eds. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. London: Arnold, 2000.

–. “The Melodramatic Field: An Investigation.” Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film. London: BFI Pub, 1987.

Guerrero, Ed. Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Kendall, Steven D. New Jack Cinema: Hollywood’s African American Filmmakers. Silver Spring, MD: J.L. Denser, Inc., 1994.

Massood, Paula J. Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film. Culture and the moving image. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003.

Mulvey, Laura. “Notes on Sirk and Melodrama.” Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film. London: BFI Pub, 1987.

Reid, Mark. “The Black Gangster Film.” Film Genre Reader II. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Taubin, Amy. “Girl N the Hood.” Sight & Sound. No. 3.8. Aug 1993.

Vicinus, Martha. “Helpless and Unfriended: Nineteenth Century Domestic Melodrama.” New Literary History. Vol. 13, No. 1. Autumn 1981.

Watkins, S. Craig. Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Williams, Linda. “Melodrama Revised.” Refiguring American film genres: history and theory. Ed. Nick Browne. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

–. Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001.

[…] 2. The Geography of Melodrama, The Melodrama of Geography: The ‘Hood Film’s Spatial Pathos. As the Boyz N The Hood anti-hero Doughboy so elonquently stated while eating a fresh pomegranate on his mother’s porch, “Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what goes on in the hood”… except of course, when they do. Spend a good solid 30 minutes getting your heady academia on with this posting from the University of British Columbia’s online film journal. Don’t worry, there’s pictures. Sorta. [Cinefile.ca] […]