Colleen Montgomery

While the resurgence of a “cinema des producteurs“1 and the development of the highly popular “film d’action” genre (Higbee 298) dominated the landscape of French mainstream cinema in the 1990s, the decade also witnessed the re-emergence of a politically committed, or what Powrie terms “New Realist” French cinema. New Realism, Powrie states, “refers less to a defined movement in French cinema […] sharing a political agenda, and more to a diverse group of film-makers who effected a re-engagement with sociopolitical subject matter” (16). Film makers such as Karim Dridi and Mathieu Kassovitz, whose films of the early to mid-nineties, Bye Bye (Dridi 1995), La Haine (Kassovitz, 1995), and Métisse (Kassovitz 1993) explore issues of xenophobia, unemployment, the ever-widening ‘fracture sociale‘ dividing the haves and the have-nots in French society and the important subculture emerging among those most negatively affected by these social iniquities, the youth of the cités or banlieues.2

Following Hebdige, I will argue that the banlieue subculture which Dridi and Kassovitz examine in their films, constitutes a form of “semiotic guerilla warfare” (Eco 105) waged by the disenfranchised youth of the suburban French ghettos against the “the ruling ideology” (133) of normative French culture. It is, to use Hebdige’s term, a form of ‘noise’ that disrupts and subverts the established order on several levels: musically, through rap and hip hop; graphically, through tagging and graffiti artwork; stylistically, through manner of dress (i.e. oversized shirts, baggy jeans, backwards baseball caps,etc.), and orally, through a lexicon of words and expressions known broadly as the “langue des cités” or the “téci” (Messili and Ben Aziza 1). Dridi and Kassovitz’s films prominently feature each of these elements of banlieue culture from Moloud’s (Ouassini Embarek) recurring rap in Bye Bye to Said’s (Saïd Taghmaoui) hip hop inspired outfits and tag art in La Haine, but it is on the last form of noise, the téci that I will focus in this paper. For while the visual elements of style of dress and graffiti, as well as the musical component of banlieue culture remain intact in the subtitled English versions of the films, the oral lexis of the téci is greatly impoverished and often almost entirely erased. The elimination of the téci in these subtitled English versions of Dridi and Kassovitz’s work, I will argue, effectively silences the ‘noise’ of banlieue subculture and undermines the film’s underlying political message of resistance and empowerment.

To provide a basic framework for discussing the specific challenges involved in translating the language of the banlieue or téci for an English speaking audience, it is important to first note the constraints inherent in the linguistic transfer of an oral source text to a written translation or subtitle. Mailhac identifies several key factors that mitigate the transposition of a piece of verbal communication into written communication within the body of a film, namely: spatial constraints within the film frame, the disparity in time required to cognitively process oral versus written forms of communication, viewers’ reading speed (which will vary in accordance with degrees of literacy, age and fluency in the language spoken), and the need to coordinate the visual appearance of text onscreen with both the image of speaker and the temporal occurrence of the utterance, while taking into account camera movements and frame changes (129). Mailhac concludes that due to both spatial and temporal constraints “the move from speech to writing [in a film] requires a substantial amount of compression” (130) and, one might add to Mailhac’s assertion, also a substantial amount of omission. Some translation theorists contend that preserving the original soundtrack – and thus the audible presence of the source language in a subtitled film – preserves the “foreignness” of the source text, enabling the viewer/reader to “experience the flavour of the foreign language […] and the sense of a different culture more than any other mode of translation” (Szarkowska). I will argue, however, following Mailhac, that the extensive truncation that subtitling imposes on a filmic text necessarily “leads to a linguistic leveling out of dialogues by neutralizing or eliminating marked features […including] syntax, levels of speech, social or geographical origin, and style” (131). Nornes furthers this argument stating that “facing the violent reduction demanded by the apparatus [of subtitling, as delineated above] subtitlers have developed a method of translation […] that violently appropriates the source text” (18). Thus, subtitling arguably eliminates or domesticates the cultural references or “foreign flavour” of the source text, while simultaneously seeking to “smooth over this textual violence” (ibid) so as to still seemingly deliver audiences an “authentically foreign” experience. Following Nornes, I will strive to demonstrate in this paper that the English translations of Bye Bye, La Haine, Métisse can be interpreted as a form of textual violence that silences the noise of the téci, and thus depoliticizes the films’ representation of banlieue subculture.

“Le Téci”: The Language of the Banlieue

The téci (an inverted and truncated term derived from the phrase “langue des cités” or language of the suburbs) is, as Messili and Ben Ben Aziza explain, a “diverse, codified language” (2), both a product and an expression of banlieue subculture. The téci violently alters and appropriates normative French, primarily through the processes of verlanisation (word inversion) truncation, the violation of standard French grammar and syntax, and the inclusion of words from a variety of other languages. It is a “fracture linguistique” (Messili and Ben Aziza 3): a linguistic manifestation of ‘la fracture sociale‘ that, in violating the structural, stylistic and grammatical rules of academic or standard French, functions as a rejection of cultural heterogeneity and xenophobia in contemporary French society. In creating for themselves a shared and hermetic form of communication, the youth of the banlieue reverse the exclusion they feel as outsiders in French society as a result of intense racial discrimination, unequal access to education and employment opportunities, and relegate the French establishment to the position of outsider or other. The téci both willfully mutilates the French language, and simultaneously provides the formerly excluded subset of the French population, the banlieuesards, with their own exclusive community, united through shared language. Thus the téci is arguably both a marker of otherness for the youth of the cité (in relation to mainstream French society) and a marker membership or belonging (in relation to the community of the banlieue) that denotes an individual’s class and social status.

The English translations of the aforementioned films, however, ‘smooth over’ the elements of resistance that are at the core of the téci (and banlieue subculture) in three primary manners. First, the transposition of the téci into normative English or widely recognizable and commonly used forms of English slang, prevents the téci from functioning as a marker of both otherness and membership and thus impoverishes the dialogue the films construct between the normative and the marginal. Second, the English subtitling of the téci in the aforementioned films eliminates both the temporal and regional specificities that characterize the téci – a vibrant and ever-evolving language – and renders it as geographically heterogeneous and temporally fixed. Finally, the translation of all three of these texts frequently privileges the substitution of complex subcultural linguistic creations for simple comprehensible references vis-à-vis the language and culture of the target audience.

The Téci as Marker of Otherness

Of the three films discussed in this paper, the use of language and the téci to differentiate characters in terms of their social and class backgrounds is perhaps most salient in Kassovitz’s Métisse. In Métisse, Kassovitz ironically reverses the colonial dichotomy of the ‘rich white Parisian Frenchman’ and the ‘poor black man of the ghetto,’ presenting instead a distinguished, rich black man originating from a long line of diplomats, and a poor white man indoctrinated into the ghetto culture of the banlieue in which he lives. In the French dialogue there is a marked difference between Félix (Mathieu Kassovitz) and Jamal’s (Hubert Koundé) speech in terms of speed, enunciation, syntax, grammar and use of slang and téci. Jamal speaks noticeably more slowly than Félix, clearly enunciating his words, using proper syntax and grammar. Though his use of slang increases through the course of the film as he becomes friends with Félix, his slang is largely of the repertoire of standard “Français familier” or familiar French slang that would be both used by and comprehensible to the average French person. Félix on the other hand, employs a much greater amount of slang and téci, most notably, verlanised words such as “meuf” in the place of femme, keuf in the place of flic (cop) as well as a large number of mild to moderate expletives such as merde, putain, cul, etc. Félix also reverses the traditional word order in certain sentences, thus violating syntax and grammar rules, saying for example “la ferme” instead of “ferme la” (an expression which loosely translates as “shut it”) and using an assortment of English words (a characteristic element of the téci) such as “du shit” for drugs, or “flipper” for “freaking out” or “flipping.” The English translation of the characters’ dialogue, however, significantly reduces the marked differences in their style and levels of language. Félix’s téci is largely downplayed and translated to common English slang words. Meuf for instance, a word which at the time would only have been used by a banlieuesard, becomes “babe,” a term that also qualifies as slang in English, but does not carry the same social and class connotations as the verlanised meuf. Moreover, his improper word order is rearranged in English to conform to standard grammatical sentence construction, and his English slang loses its significance as an element of subversive language when it fits seamlessly into the text of the target language. Thus the translation of elements of the téci into normative English or widely recognizable English slang impoverishes Kassovitz’s subversive dichotomy of the ‘gangster white boy’ and the ‘sophisticated black man,’ diminishing Félix’s otherness in relation to French mainstream culture.

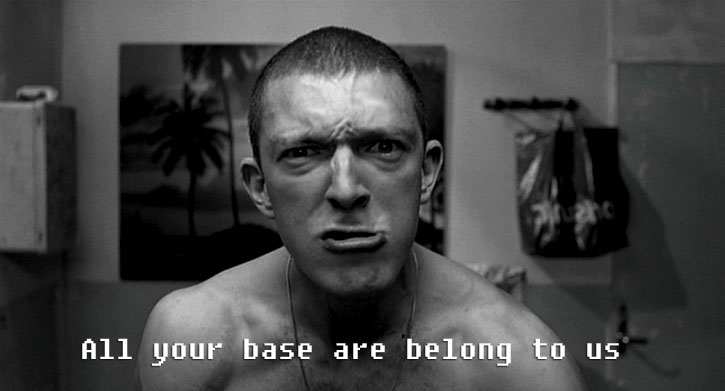

Though all of the main characters in La Haine employ the same general level and style of French, as they all speak predominantly in téci, there is still a palpable loss of otherness in the English translation of their dialogue. What is most noticeable in the translation of La Haine is the simple omission of a great deal of téci dialogue. This is likely due in part to the characters’ wordy, rapid-fire conversational style that, as previously stated, must be truncated in order to conform to the spatial and temporal restrictions of subtitling. Furthermore, the characters’ prolific use of verlan or word inversion loses its political meaning in the transition from French to standard English slang. Though it may seem a simple game of syllabic reversal, the verlan is more complex than it may at first appear. The verlan,3 in fact operates as a sort of re-encoding of a text through the reordering of the alphabetical structure and syllabic intonation of a word. According to Messili and Ben Aziza, there are three principal ways in which a word is verlanised: a simple inversion wherein Paris becomes ripa; an inversion and the subsequent addition of another sound as in the case of soeur, which becomes reus, and subsequently reusda; and finally an inversion and subsequent suppression of the final vowel or syllable of the verlanised word as with flic, which becomes keufli, and finally keuf. Words, however, are not limited to one of the processes of verlanisation and some words can undergo all three processes. For example, the verlan of the expression “en douce” (on the sly) is first inverted to become en ousde, then an additional sound is added to generate en lousde, and finally the last syllable is suppressed, producing the final verlan expression – en lous. In each of these three cases the syllabic intotaion, which in French generally falls on the last syllable, is transferred to the second last syllable (as with Paris and ripa). The verlan is therefore both an appropriation and rejection of standard French, that defiantly changes the look and sound of a word as an act of rebellion against normative French culture. The verlanisation of any given word is thus always subject to a certain amount of random variation and ambiguity, and verlanisations tend to emerge organically within the banlieue as they are created and put into practice by the inventors and innovators of the coded language. This complex system of random selection that generates the verlan helps to preserve the hermetic nature of the language and ensures that the mainstream French community is consistently relegated to the ideological position of the other, the outsider. When verlan words are nonetheless successfully integrated into mainstream French (as is now the case with words such as meuf , keuf and beur), they are then subjected to a reverlanisation, to reappropriate the word for exclusive use within the cité community. The implications of this process of reverlanisation will be touched upon in greater detail further along in the paper.

Returning to the use of the verlan in La Haine, it is significant to note that the entirety of the nuanced, intricate series of steps that produce the verlan are entirely lost in the English translation of the film. The political significance of these words, constructed as a reversal and rejection of normative French, is rendered invisible in the subtitles, which bear no witness to the linguistic complexities involved in the construction of the verlan. The word “pig” for example which often intervenes as a replacement for “keuf” (the verlan of flic– slang for police) in La Haine has its own set of connotations as an English slang word, but carries no tangible trace of the political act of refusal, or the linguistic creativity involved in generating the verlan source word keuf. Certainly, audible traces of the verlan are discernable throughout the film, and frequently repeated words such as meuf and beur may become noticeable even to non-French speaking viewers; however, the fundamental notions of rebellion these linguistic mutations represent are lost in the English translation of La Haine.

The Téci as Temporally Fixed and Regionally Specific

As alluded to in the previous discussions of the téci, some téci terms, particularly verlan expressions are, over the course of time, imported and integrated into mainstream French slang. Because the téci is devised as a secret language reserved for the spatial and cultural locale of the cité, the exportation of words into standard French is highly problematic. Téci words that filter into mainstream French become divested of their exclusionary powers and are thus no longer useful in the lexicon of the téci as units of political and cultural rebellion. In order to restore a word’s political agency, it must be put through another series of mutations, to reappropriate it as an authentically téci term. Due to the steady rise in the popularity of rap/hip hop culture in France since its introduction in the early 1980s and through the 1990s, the téci, which can be found in most rap and hip hop songs, has become increasingly accessible and exportable in contemporary French society. Words used in songs by rap and hip hop artists, composing in the téci, are quickly and easily absorbed by young listeners and subsequently incorporated into mainstream French slang. As a result, the rate of mutation of the téci is rather rapid, to the point that words used only a decade ago in Bye Bye, La Haine and Métisse that were, at the time, characteristic of the youth subculture are now considered part of mainstream French. Notably beur, meuf, and keuf, all téci words are even listed the 2006 edition of the Larousse dictionary. Subsequently, these same words have new, reverlanised replacements in the lexis of the téci: beur has become rebeu, or rabzouz4; meuf is feum or feumeu; and keuf is feuk (a term which has the added bonus of being phonetically similar to the English word “fuck”). Consequently, for a French speaking viewer familiar with French slang and the present day forms of the téci, Bye Bye, Métisse or La Haine betray a specific temporal localization; a time when older forms of téci were still employed within the cité and still considered subversive language. The generic English slang used in place of these now-mutated téci terms, conversely, does not give an indication as to the specific temporal setting of the film. The English terms (i.e. babe, chill, and cool) have remained relatively unchanged from the time of the subtitling to the present day, and are still viable slang terms in contemporary English. The translation thus erases the temporal specificity of the téci language used in the films and fails to highlight the dynamic nature of the téci and its ongoing evolution within the French banlieue subculture.

Though barely any perceptible difference in style of speech is conveyed in the English subtitling of the three films discussed in this paper, there are significant differences in the form of the téci that is spoken in each film, in relation to the disparate regions from which the respective speakers originate. Méssili and Ben Aziza note that certain téci words have meaning in some neighbourhoods and regions of France, but not in others, and that there are highly perceptible differences between the téci of the Parisian cités and the Provincial cités of Marseille. As previously discussed, there are marked differences in Métisse between Félix and Jamal’s style of speech due to their contrasting class and regional backgrounds (Félix is lower class and a banlieuesard, while Jamal is upper class and Parisian). Similarly, there are differences in Mouloud’s, (a Parisian boy) and his cousin Rhida’s, (a Marseillais boy) style of speech. Most noticeably, Rhida speaks with the accent Marseillais, an accent colloquially referred to as the accent “chantant” or sing-song accent, characterized by a greater musicality and syllabic division of words than Parisian French. Rhida also employs a nuanced variety of téci, using words such as the French slang term “fada” to designate someone or something crazy in the place of the verlan terms usually employed in the Parisian peripheries: “ouf” (the verlan of fou, the french term for crazy), “louche” or “chelou” (the former a slang term for crazy, and the latter the verlanisation of louche), terms that Vinz and Said frequently use in La Haine, and that Max and Félix also both use in Métisse. Rhida also uses the word cagole, a specifically southern slang term for a woman in the place of the word meuf, a verlanized word for woman that also reoccurs frequently throughout La Haine and Métisse as well also in Moloud’s vocabulary (as he too was raised in the Parisian periphery.) Rhida’s vocabulary also links him more closely with the family’s North African heritage. He employs many Maghrebi French slang terms such as “la gazelle” (slang for an attractive woman) in his everyday language, that are absent from Mouloud’s vocabulary. Rhida’s manner of speech is distinctly characteristic of Marseillaise téci, as Maghrebi French slang seems to have migrated more readily to Southern regions of France, a fact likely linked to the relatively small geographic distance between Southern France and Maghreb and the high levels of immigration from the latter to the former. These regional differences however are not perceptible in the English subtitling of the films which renders Parisian and Provincial téci as seemingly identical, when in fact the variations in vocabulary, pronunciation, and intonation are great.

Several further challenges in translating the cultural concepts in French New Realist films, aside from the translation of the téci are worthy of investigation. In particular, the substitution in La Haine of French bande déssinée characters for English comic strip characters is highly problematic as it serves to further depoliticize the original French dialogue in the film. As Forsdick asserts, the bande dessinée, widely regarded in France as the ninth art, “has a status far surpassing that of the equivalent English-language comic strip” (1) in terms of its historical significance in French society, its political engagement with contemporary issues and its widespread and sustained popularity not only among children, but youth and adults as well. The most arresting replacement made in La Haine of a French bande déssinée character for an English comic book character is that of Pif le Chien for Snoopy. As Horn describes, at the start of the Cold War, the Communist Party in France decided that their journal “L’Humanité” could no longer run their staple comic strip Felix the Cat, as the comic feline was deemed “too glaring an example of American enterprise to be tolerated any longer in the pages of their official publication” (103). Pif le Chien was thus created as an authentically French replacement for the enterprisingly American Felix. Thus, the substitution of Pif for the quintessentially American Snoopy changes the political implications of the text, re-imposing an American cultural icon in the place of a fundamentally anti-American, communist character. Moreover, the substitution of Astérix for Mickey Mouse, though apt in terms of the characters’ respective celebrity status in the realm of cartoon comics, is also highly problematic. First and foremost, Astérix, like the protagonists in La Haine, is also a native of the banlieue. Astérix was first drawn by Albert Uderzo, in the Parisian periphery of Bobigny. Though it may seem insignificant, the patrimony of the character would be something of which most French citizens having read the comic would be well aware, and certainly of which residents of Bobigny would be proud. Astérix’s protection of his homeland against a military invading force evokes the police-youth conflict in the banlieue wherein youth in the banlieue see their homeland at constant risk of attack from the dominant ruling force, the police. Though Mickey Mouse is a recognizable character for both a French and certainly an American audience, the political meaning behind Astérix is erased in the English translation. Thus, in both of these instances, as with the subtitling of the téci, the translation becomes “a labour of acculturation” (Venuti 5) that appropriates and domesticates the film so as to provide English-language viewers with the “narcissistic experience of recognizing his or her own culture” (ibid) within the film.

The malaise of the youth inhabiting France’s marginalized urban peripheries and the subculture that has grown up around them as a result of their sense of exclusion from and subsequent rejection of French cultural norms, has not only continued on beyond the 1990s but has arguably intensified, as the wide spread rioting in banlieues throughout France in September of 2005 demonstrated. While the fracture social in French society clearly remains, it is my hope that new modes of translation might succeed in mending the fracture linguistique between the original French and subtitled English versions of New Realist films. Though, as Chaundhuri writes “whatever creative energies it might unleash […] a translation or rendering must always be inadequate, never a total reflection or equivalent of the original” (23), I do believe, nonetheless, that new models of translation are necessary to adequately transpose and convey the deep cultural and political implications of the ‘noise’ of banlieue subculture and téci for non-French speaking audiences.

Works Cited

Chaudhuri, Sukanta. Translation and Understanding. New Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Forsdick, Charles. “The Francophone Bande Déssinée” New York : Rodopi, 2005.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. New York: Methuen, 1979.

Higbee, Will. “Towards a Multiplicity of Voices: French Cinema’s Age of the Postmodern, Part II- 1992-2004” French National Cinema. Susan Hayward. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge (2005): 293-327

Horn, Maurice. “Pif Le Chien (Snoozle the Dog)” The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Ed. Maurice Horn Vol 1 p. 103. Philedelphia: Chelsea House, 1976.

—. “Astérix” The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Ed. Maurice Horn Vol 5 p. 616-617. Philedelphia: Chelsea House, 1976.

Mailhac, Jean Pierre. “Subtitling and Dubbing, For Better or Worse? The English Video Versions of Gazon Maudit” On Translating French Literature and Film II. Ed. Myriam Salama-Carr Atlanta: Rodopi (2000): 129-154.

Mera, Miguel (1998) “Read my lips: Re-evaluating subtitling and dubbing in Europe” Links & Letters 6, 1999, pp.73-85.

Messili, Zouhour and Ben Aziza, Hmaid. “Langage et exclusion. La langue des cités en France”, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, vol. 69 Etre marginal en Méditerranée (XVIème – XXIème siècles) p.1-8, 10 may 2006. <http://cdlm.revues.org/document.html?id=729&format=print>.

Nornes, Abé Markus. “For an Abusive Subtitling” Film Quarterly 52.3 (1999).

Powrie, Phil French Cinema in the 1990s: Continuity and Difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999.

Szarkowska, Agnieszka “The Power of Film Translation” Translation Journal. Mar 2005. <http://accurapid.com/journal/32film.htm>.

Venuti, Lawrence. Rethinking Translation: Discourse, Subjectivity, Ideology. London: Routledge, 1992.

1. “[B]ig budget films with high production values[…] characterized by continuity; either because of their reliance on tried and tested generic formulas such as comedy, or else through their association with lavish spectacle and high production values of the tradition de quality” (Higbee 298).

2. Broadly translated in English as “suburb” the terms cité and banlieue refer to the communities or towns on the periphery of urban centres, often consisting largely of socially subsidized housing complexes.

3. The word verlan is itself a verlanisation, of the word “l’envers” meaning backwards.

4. Les arabes with the liason from the s forms zarabes, which is then inversed to form rabza. Subsequently the final a is suppressed and the extra sound ouz is attached to form rabzouz.

you make an error when you try to explain “the téci” la téci ( in verlan ) it’s cité/suburb the real name of this language is argot (slang in english if i don’t make an error) the téci is only a place not the name of a language , but i agree with you , this movie is extremly hard to translate ,cuz argot from french’ suburb use many reference that only french people can know, verlan , and many words from other culture , if your not french , it’s really hard to understand it , but i think is like gangstas language or latinos in usa….

Thank you for this enjoyable and informative read.

Just re-watched La Haine after what feels like far too long; listened through headphones for the first time to really absorb the language. It’s been 10yrs since I let my French tarnish after college but I was fascinated by what I was hearing. I could understand characters such as the gentleman whose friend Grunwalski froze to death quite easily, and the subtitles were accurate enough to what he was saying for me not to be distracted by them. Some of the speech of the parents of the main trio was the same but, I was struggling to understand the fullness of the banter going on elsewhere. I could hear that the grammar was all over the place and see that the subtitles were not accurate (although I do have the version with Astérix and Pif le Chien referenced). Your article has made this all much clearer; thank you.

I also found it interesting that the lads ‘poshed up’ their speech during their visit to the art gallery, and over emphasised their Ps & Qs, as it were.

I’d like to track down a script; it would be interesting to attempt translating the subtext as well as the plain text.

I feel pretty lucky to have encountered your site and look forward to more enjoyable posts here.