Katherine Barscay

Kathryn Bigelow does not make feminist films. Or so she says. Why then, do critics and academics alike continue to search for a feminist polemic or, at least, a female perspective in all of her films? For the most part, Bigelow does choose to work within genres that have been coded as decidedly male. Her films play with concepts of the western, the horror, the road movie, the thriller, the science fiction film, and the cop film, most of which are considered to have a target demographic that is predominantly, although by no means exclusively, male. As a result, the desire to find a feminist agenda in her films is entirely understandable. To date, she has made seven features, all of which emerge out of different genres, but share a number of tropes, such as the creation of alternative family units and the glorification of outsiders. Her films manage to defy classification, never wholly belonging to one specific genre. These films are very much about blurring boundaries, especially those that surround gender and genre, as well as playing with typical portrayals of families and outsider groups. This does not necessarily make the films explicitly feminist, as they are more concerned with refusing traditional means of classification then explicitly engaging with a feminist polemic. In fact, being labeled as a feminist director is something that Bigelow actively resists, because, for her, the hope is that we will one day arrive in an era where the gender of the filmmaker is irrelevant. Perhaps it is for this reason that her films are primarily concerned with gender and genre. By blurring the boundaries of both, as well as creating alternatives to traditional representations of family and outsiders, she emphasizes the inconsequentiality of classification. Bigelow’s films and characters, like Bigelow herself, refuse to be categorized in traditional ways; perhaps in itself, this is a form a resistance.

Trying to find a female perspective in films made by women is more problematic than one might imagine. By finding something that is distinctly female and different about a woman filmmaker, she remains categorized as an outsider or, in any case, different from the norm. While there are certainly many more female directors working in Hollywood now than during the studio era, they are still often relegated to the so-called ‘women’s picture’ and when one steps outside of the genres of the melodrama or the romantic comedy, there is always a certain amount of confusion. Even directors who have been highly praised, such as Sofia Coppola, continue to work on films that centre on the difficulties of a female protagonist. While Bigelow has made two films that center on women (Blue Steel and The Weight of Water) the majority of her films are actually concerned with male protagonists within the context of the action film. Why would a woman want to work in the horror or action genre? These are genres that have constantly been associated with a male viewpoint and a privileging of male ideals. However, the more we draw attention to her status as a woman director in a male dominated field and the more we look for something in her films that makes them explicitly different, the more she seems like an anomaly. As Pam Cook would likely argue, this desire to find the director’s gender in a film’s content and style is not necessarily a productive means of reading a film (228). The more we find specific female views coming from a director, the more we draw attention to the limits, boundaries and inherent differences that gender creates. For Bigelow, there is not a “feminine eye or a feminine voice. You have two eyes, and you can look in three dimensions and in a full range of color. So can everybody” (qtd. in Jermyn 134). Bigelow strives to avoid categorization, because she does not want her gender to describe who she is as a filmmaker. She sees herself as “an author before or outside her gender, as a filmmaker for whom the category or label of female is irrelevant” (Jermyn 5).

Bigelow began her film career in the independent sector before moving into mainstream action cinema. The fact that she is well-versed in film theory is evident in her films. A graduate of film school, Bigelow would have encountered and engaged with the theoretical side of film but she chooses to work in genres that are accessible to the mainstream, where her ideas will reach the widest audience. By examining gender through genre with this strategy, she is truly changing the nature of being “an outsider on the inside” (Redmond 107). The idea of appropriate gender behavior is complicated in Bigelow’s films as it is complicated in the work of Judith Butler, where she argues that gender is, in many respects, a performance. Butler’s “concept of gender as a learned set of characteristics that has assumed an air of naturalness and her claim for the destabilizing effect of drag as gender parody opens the door for a less deterministic reading of the action heroine” (Brown 53), one who can draw attention to the performative nature of gender through her masculine traits. In this sense, the female action hero becomes a version of drag, which “in imitating gender, implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself – as well as its contingency” (Brown 55). A character like Mace in Strange Days certainly fits with this set of ideas, as it is she who becomes the protector and bodyguard of her male friend and her strength and physique are constantly stressed in the context of the narrative. Yet, Mace is still very much coded as feminine and the film is filled with scenes that depict her as a loving and caring mother. Bigelow reveals the arbitrary nature of gender and she plays with this in her characterization of women, as “she brings into relief the constructedness of gender in a way that frames her own status as a woman director in terms of performance (rather than innate femininity)” (Lane 1998: 61). She is inherently aware that she cannot escape her gender and is constantly struggling with how she is perceived, in the same way that many of her female characters do. Often classified by her beauty in a way that a male director never would be, Bigelow has attempted to complicate this characterization, to a certain extent, by appearing in production stills or at film premeieres dressed in leather jackets and baseball caps one moment, and skirts and dresses the next. She is continually highlighting the performative nature of gender, both in the construction of her own star persona, as well as in her films. As Pam Cook notes, there is something self-conscious in the way Bigelow presents herself publicly, and there is a “hint of masquerade about many of her publicity shots, which suggests a self conscious play with gender roles” (230) akin to what we see in her films.

Bigelow’s first feature-length film, The Loveless (1982), followed a group of bikers led by Vance (Willem Dafoe) and Davis (Robert Gordon), who stop to fix their bikes in a small town. They meet Telena (Marin Kanter), a girl who is sexually abused, and Vance begins an affair with her. The film culminates in a raucous bar party where Telena shoots her father and then herself, after which the bikers ride off, continuing along the road. The film came four years after her twenty-minute short The Set Up, which depicted two men fighting while two other men philosophize (in voice over) about the theoretical nature of violence, in what seems to be a typical product of film school education. The Loveless transcends this humble student film, but it remains closer to an art-house picture than the action blockbusters that generally define Bigelow’s career. Bigelow was only just emerging from the world of art school, and it seemed as if she had yet to find her connection to fast-paced action films. In her own words, Bigelow “hadn’t embraced narrative at that point; [she] was still completely conceptual, and narrative was antithetical to anything in the art world” (qtd. in Smith 30). However, despite its art-house roots, The Loveless remains a quintessential Bigelow film, for it plays with the ideas of gender and genre, as well as issues of family, that are visible across all her films.

The film is clearly a hybrid, drawing on conventions of the road movie and the biker movie, while evoking 1950s nostalgia that was common in 1970s America. Bigelow even goes so far as to include Robert Gordon in the cast. Himself a symbol of nostalgia, Gordon was a 1970s singer who continually paid homage to 1950s music. A film that is “neither fish nor fowl” (Bigelow qtd. in Smith 30), The Loveless is a unique blend of two genres and it marks the beginning of a form of generic experimentation that distinguishes all of Bigelow’s films. In terms of gender, it is obvious that Bigelow had already started to blur the boundaries. The film begins with a lingering shot of Dafoe’s bike. The machine continues to be shot in this fetishistic way throughout the film (indeed, in many of Bigelow’s films, machines become subject to a fetishistic gaze). The machine becomes powerful and beautiful in the same way that the camera does. This fetishization of the bikers and their bikes evokes Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1964), a film that is famous for its latent homoeroticism and for fetishizing bike culture and 1950s nostalgia. With this not-so-subtle reference, The Loveless becomes overt in its demonstration of homoerotic subtext. The bikers are tough guys, throwing knives at each other for fun, but they are also highly effeminate. Both Willem Dafoe and Robert Gordon have fairly boyish features, setting them up as characters who are caught in-between two genders. Gordon’s look embodies the 50s, sporting a “black pompadour, pouty mouth, big dark eyes with long eyelashes and lanky grace” (Stilwell 37), but this description also links him to the feminine, as does his relationship to Hurley (one of his fellow bikers). At one point he even says, “Hurley baby, I wouldn’t think of going nowhere without you.” Already in her debut, Bigelow is demonstrating her interest in male relationships and issues of masculinity.

Female gender is also called into question through Telena, the decidedly androgynous girl who the bikers meet at a gas station. Unlike the waitresses, who are either repulsed or attracted to Vance’s bad boy status, Telena appears noticeably under-whelmed. She has a no-nonsense approach to Vance’s gang and, while she wears a pink top, she also sports pants, cropped brown hair, a raspy voice, and generally boyish features. In this film there is little that separates Telena’s masculinity from Vance or Davis’ femininity. Vance also has a boyish face and the resemblance between the two is not to be overlooked. Vance and Telena become foils for each other, embodying both masculine and feminine, but neither wholly one nor the other. When we see a post-coital shot of the two, they are pictured one on top of the other so that their bodies appear alike. In general, the gendering of the bikers and Telena becomes hyper-stylized along with the film, so much so that one cannot help but be made aware of the performative nature of gender. The waitress who strips in the bar demonstrates this relationship overtly. She is performing and is ultimately mocked by the bikers for her obsessive attempt to feminize herself in the traditional heterosexual context of occupying the male gaze. These bikers, however, are not complicit in this gaze.

The bikers are typical Bigelow outsiders, and there is something appealing, or at least seductive, about their characters. We are both seduced and repulsed by them. One character demonstrates this by saying “they’re animals,” only to counter that he wishes he could be one of them for a day. In this respect, being on the outside is not necessarily coded as negative, which we could connect to Bigelow’s own position as a woman working in a male-dominated field; she doesn’t quite fit in. In the case of The Loveless, the bikers have formed a kind of surrogate family, with Davis and Vance seeming to wrestle for the role of the patriarch. Their family is non-traditional but it appears to be no less functional (perhaps even more so) than traditional family relationships. The theme of incest that surrounds Telena and her father depicts the traditional family relationship as one filled with perversion. This so-called ‘traditional family’ has been so twisted that Telena’s only means of escape involves killing her abusive father and then taking her own life, after which the bikers ride on, seemingly unaffected and wholly comfortable in their dysfunctional family unit. This idea of the alternate family unit is something that emerges in many of Bigelow’s texts; the viewer is drawn into these alternative families, and often, finds comfort within them.

The idea of dysfunctional families also plays a role in 1990’s Blue Steel, where the idea of a female character comfortable in a role that is coded as conventionally male finds its literal representation. This film centers on Megan (Jamie Lee Curtis), a rookie cop who is caught up in a killer’s twisted obsession with violence and authority. Megan meets Eugene (Ron Silver) after she is involved in a hold-up bust gone wrong. They begin a relationship, but it soon becomes evident that Eugene is a serial killer who has become obsessed with Megan. Megan must then team up with her partner Nick (Clancy Brown) to bring Eugene to justice. Within the film, Bigelow plays with the traditional cop drama but many of her artistic choices complicate the simplicity of this genre. Often, Bigelow evokes conventions of the horror and rape-revenge film, with Megan occupying the position of the ‘final girl,’ fitting Judith Butler’s conception of the ‘final girl’ in slasher films. These women are characterized by “a continuous contest between generic conventions which would position her as a victim and those which enable her to defend herself” (Butler 45). In light of this, the casting of Jamie Lee Curtis as the female lead becomes an interesting choice for a number of reasons. Labeled as the ‘scream queen,’ Curtis was well-established as the typical ‘final girl’ in a number of slasher films. In these films, the woman is always a victim; taking her out of this genre and turning her into the strong-willed cop makes a bold statement about female victimization. Curtis cannot escape the characters she has played in the past and, as a result, in this film she becomes both hero and victim. Curtis’s androgynous appearance, and her rumored possession of XXY chromosomes (which is widespread on the internet and has taken on a somewhat ‘mythic’ status), also allows her to be somewhat caught between the masculine and feminine worlds. This is reflective of what Megan is facing in her professional career. Once again, Bigelow has used popular culture and celebrity to influence her casting, which draws attention to ideas of gender and its construction.

Early in the film, Megan struts down the street in her uniform and is smiled at by two women. The fact that the women notice Megan seems to be evocative of her ability, according to Christine Lane, to transgress “conventional body politics” (1998 72). She is, in fact, portrayed as more masculine than the male convenience store clerk whom she also encounters while in uniform. Her uniform is, in many respects, a symbol of her identity crisis. As Yvonne Tasker observes, she has “acquired a confident control of space” (159) through dressing up in this traditionally male uniform, but she is nonetheless still ‘dressing up’; she is performing. After this opening sequence, the film cuts to Megan dressing. Her crisp, masculine police uniform is in stark contrast with her lacy bra. The film foreshadows her future struggle between masculine and feminine ideals, while also allowing viewers to enjoy the “pleasures of masculine mobility and agency without eclipsing femininity as a cognitive position” (Butler 45). Megan’s bra codes her as distinctly feminine, but her position of authority places her in a more masculine role. This oscillation between masculine hero and feminine victim once again evokes the theories that surround the ‘final girl’ in the slasher film.

Megan, like Vance, sits in a precariously balanced position on the border of conventional gender roles. Megan is not accepted by the police world, nor is she at ease outside of it. Characters are always questioning her desire to work in this masculine field: “you’re a good looking woman, beautiful in fact; why would you want to be a cop?” Her own father is disappointed by her departure from traditional gender roles, saying, “I’ve got a goddamn cop for a daughter.” Megan’s relationship with her father becomes evocative of the perversion of the traditional family unit that we encounter in so many of Bigelow’s films. Like Telena’s father, Frank is highly abusive both towards Megan and her mother. Later in the film, Megan reveals the truth about why she wanted to be a cop. She answers this often-asked question with one word: “him.” This is an ambiguous answer, as the ‘him’ in question could be Eugene, her father, or abusive men in general. Or, conceivably, it is reflective of her desire to obtain a position of male power. Perhaps this is representative of the way that Bigelow is questioned for her choice to direct in the male-dominated world of action cinema. Megan points the gun, as Bigelow points the camera. Even the opening depiction of the gun is easily connected to Bigelow’s camera. The shot of the spinning of the chamber has the effect of a spinning movie reel, perhaps once again connecting Megan’s object of power with Bigelow’s. Like the camera, the gun is seen as an object of traditional male power. The shot of the bullets entering that chamber take on a particularly sexualized and phallic connotation. Yet, Megan is not immune to gender stereotypes herself. At the opening of the film, Megan participates in a police training activity where she enters the scene of a domestic dispute and must determine whose story to believe. Here, she mistakenly assumes the woman to be the victim in a case of domestic violence, when the roles were in fact reversed. This foreshadows the revelation of Megan’s own abusive family. It also serves as a message to the audience, a warning that we could connect to much of Judith Butler’s work, wherein she advises “against making conventional assumptions about the gendering of violence” (44).

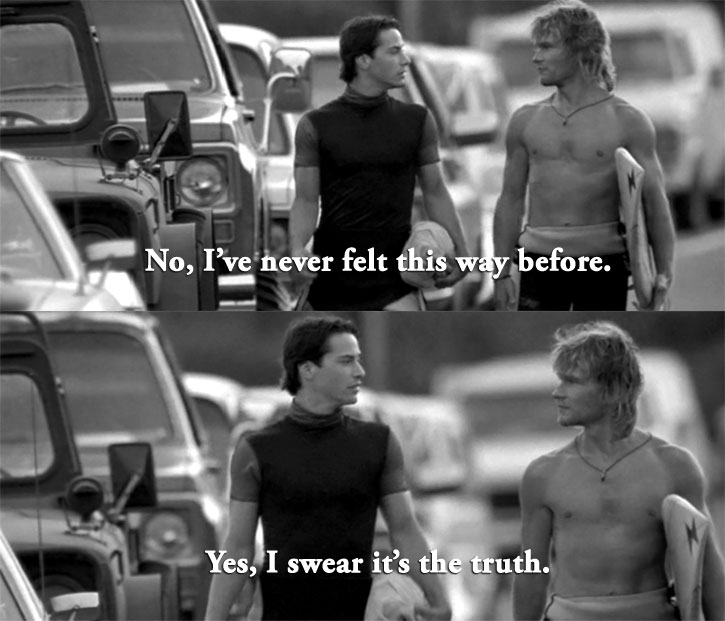

In Bigelow’s next feature, Point Break (1991), she once again looks at male relationships and masculinity, this time in the context of the thriller genre. The film takes on the idea of the rookie cop that we encountered in Blue Steel, only this time we are aligned with Johnny (Keanu Reaves), a rookie FBI agent. Johnny teams up with a senior agent, Pappas (Gary Busey), in an attempt to determine the identities of a group of bank robbers whom Pappas suspects to be surfers. Johnny then goes undercover with the surfers to gather evidence, but ends up captivated with their world, beginning a relationship with Tyler (Lori Petty). He becomes obsessed with their leader, Bodhi (Patrick Swayze), ultimately following him to the far corners of the globe to capture him, only to let him drown himself in the final moments. Still blending genres, the film draws on the rookie cop film, the Western and the male buddy film, creating what Bigelow herself refers to as a “wet western” (qtd in Lane; 2000 118). The film opens with images of Bodhi surfing crosscut with Johnny doing a target practice test in the rain. As Redmond notes, the way that the scene is edited makes it seem as if Johnny is shooting at Bodhi, foreshadowing their conflict as two men on either side of the law (109). The opening scene also set up the issues of masculinity that will shape the film. Johnny is proving his masculinity through the test, cocking his gun and taking out the bad guys as he will continue to do throughout the film. Masculinity remains an issue in the film through Pappas and Johnny’s relationships with the night-shift cops, as well as with agent Harp, to whom both Pappas and Johnny have to answer. The men in this film always seem to be jostling for a position in the pecking order, but masculine relationships are also important. Johnny’s relationship with the aptly named Pappas becomes one of father-son guidance, with Pappas praising him but also putting him in his place as a rookie.

Masculinity is hyperbolized in Point Break, taking on an almost melodramatic role as viewers witness machismo transformed into “overblown spectacle” (Grant 380). This excessive quality calls attention to its performative value. After all, Johnny is undercover; he is performing. Johnny constantly has to prove his masculinity to the surfers in order to be initiated. Here, we have another gang of outsiders that are strangely alluring for both Johnny and the audience. There is something romantic about their lifestyle, totally free from the conventions of traditional society. It is, as Bodhi says, them “against the system.” Once again, there is an alternative family unit formed. Bodhi becomes the father figure and the love he has for “his boys” is obvious in the way he cares for them after they’ve been shot. Here again, a character is seduced by the lifestyle of the outsiders and, in this case, Johnny ultimately rejects the law and chooses that path. In the end, he throws away his badge, choosing instead to live by the waves as his ‘father’ did.

There is certainly no denying the homoerotic undertones that exist in this film, as they do in The Loveless. While this idea is often explored within the context of the male buddy film, I would argue that Bigelow uses it play with traditional gender roles, relegating Johnny to position of the female love interest in action films, while also evoking the seductive nature of an outsider figure. The two men develop a relationship over the course of the film, but even their first meeting has a homosexual subtext, as Johnny gazes longingly at Bodhi surfing. Ultimately, Johnny does get “too goddamn close to this surfing buddy of [his].” Johnny and Bodhi are always engaging in some sort of competition, from football to sky diving, but there is a mutual respect and admiration that seems to develop between the two. They bond through masculine activities, such as taking on the surf Nazis together. Here, Bodhi is able to save Johnny, and Johnny becomes the damsel-in-distress figure. Over the course of the film, Johnny becomes more connected to Bodhi and his lifestyle. Obviously, the plot lends itself to Johnny’s concern with Bodhi, but the film seems to move beyond that, as Bodhi longs to teach Johnny the spiritual side of surfing and show him itas a “state of mind.” It is certainly significant that Bodhi’s name means enlightenment (Redmond 119) and he does take Johnny “to the edge, and past it,” leaving behind the borders of traditional male relationships and telling him that “we’re gonna ride this all the way, you and me Johnny.” Even when Johnny’s job requires him to capture Bodhi, he is unable to do it. After a long and fast-paced steadicam sequence of Johnny chasing Bodhi, Johnny has the opportunity to shoot him. We know from the opening sequence that Johnny is a crack shot, but he does not shoot. Instead, there are a number of lingering shots of the two characters looking into each other’s eyes as Johnny recognizes that he is unable to hurt Bodhi. Even when Johnny is reunited with Tyler at the end of the film, he gazes beyond her and watches Bodhi drive away. Johnny becomes obsessed with Bodhi, tracking him to the other side of the world (significantly without Tyler), only to let him have his final wave. It is not without consequence that the final moments of the film focus on Johnny and Bodhi and that Johnny has now adopted Bodhi’s long shaggy hair, having chosen to reject his traditional lifestyle.

With Point Break, the idea of gender and traditional heterosexual roles is being played within an extremely mainstream film that still adheres to the conventions of the action film. The hyper-masculinity that the film embodies is clearly a reaction to the ‘hard-bodied’ male action hero of the Reagan era. The inclusion of the Reagan mask as Bodhi’s disguise seems like a conscious choice that draws attention to the ideals that were privileged in Reagan’s era and satirizes them. Coming out of the aftermath of Vietnam, America was looking for a re-affirmation of power and the ‘hard-bodied’ male action hero that thrived in the Reagan era was just the answer. As Jeffrey Brown states, with the “obvious emphasis on masculine ideals, action films in the 1980s seem to deny any blurring of gender boundaries: men are active, while women are present only to be rescued or to confirm the heterosexuality of the hero” (52). The typical 1980s action film woman was a “hysterical figure who needed to be rescued or protected and was often played for comedy. All that was required of an actress was an innocently sexual appeal and a ready scream” (Tasker 177). This is clearly not the case in Point Break, where Tyler is anything if not capable. In fact, her introduction in the film actively subverts the traditional role of the female heroine. She is introduced in a rescue, but the roles are reversed. It is Tyler that saves Johnny from the ocean, noting that he “got no business being out [there] whatsoever.” While Tyler is a part of the narrative, she seems to be little more than a common connection between the two men, a catalyst that brings them together more than an object of desire. Johnny is actually never able to save Tyler, as it is Bodhi’s choice to free her at the end of the film so he is never able to totally embody the role of male action hero.

Tyler rarely needs anyone. She is tough and reflective of the androgyny that we saw in Telena and Megan. She has short-cropped hair, a muscular physique, a raspy voice and an androgynous name. Just as Telena bore a physical resemblance to Vance, so too does Tyler resemble Johnny. In another echo of The Loveless, when Johnny and Tyler are filmed in bed their bodies are positioned so that they look surprisingly alike, again playing with the idea of gender. The shot is staged almost like a painting, shocking the viewer when it is disrupted by the sound of the doorbell. Moments later the two are filmed walking along the beach in wetsuits and their similarity is undeniable. Despite their quest for a hyper-masculinity, Johnny and Bodhi have a number of feminine traits, and Tyler even refers to Johnny as a “pretty boy.” The choice to cast Lori Petty as Tyler is obviously a conscious one, as she is known for her androgynous appearance and for playing tough, misfit characters. Bigelow was also very likely aware of the star status that surrounded Swayze and Reeves and cast them accordingly. Predominately associated with boyhood roles, Reeves had already been made famous by his portrayal of Ted in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (Herek 1989), as well as his role as Tod in Parenthood (Howard 1989). In both films Reeves plays a somewhat slow character that is on the brink of manhood, but not quite there. Even the name ‘Johnny’ brings up images of a young boy rather than a man. He is no action hero. These external influences, combined with his delicate features, actively code him as a character that evokes aspects of femininity. Swayze’s star image performs a similar function. He is most famous for Dirty Dancing (Ardolino 1987), where his dance background played an important role. In this film he is a strong man, but also one who is in touch with the delicate precision that dance requires. There is ambiguity in this, an ambiguity that is reflected in the gendering of Bodhi, on the one hand a relentless adrenaline junkie and, on the other, a “surfer in tune with nature, with water (where water symbolized the feminine)” (Redmond 119). Bigelow uses these cultural influences to help her play with gender, rendering it indefinable once again.

After a brief experiment with a more art house style picture (2000’s The Weight of Water), Bigelow returned to a big budget action picture with K-19: The Widowmaker (2002). The film centers on the crew of K-19, the Russian nuclear submarine that suffered a reactor malfunction that forced the crew to submit themselves to massive amounts of radiation in an attempt to repair the damage and prevent a nuclear disaster. For Bigelow the goal was to “make a film that shows the heroism, sacrifice and humanity of these men” (qtd. in Jermyn 12). The film opens with an intense scene revolving around a torpedo, which is ultimately revealed as a drill. As in previous films, Bigelow plays with the viewer’s expectations by using something of a false opening. Yet again, Bigelow plays with genre, using the submarine genre and drawing on films such as Wolfgang Petersen’s Das Boot (1981). Because it is based on true events, the film also blends the historical drama with the action thriller, as well as the melodrama. Like many of the pictures in Bigelow’s oeuvre (especially The Lovelessand Point Break), the film makes use of “another masculine genre where melodrama and action meet, centering on the construction of a male community set apart from the rest of society” (Jermyn 12).

By placing the characters on a submarine in the middle of the ocean, these characters automatically become outsiders. They are literally separated from any form of society and they must form their own family unit. as in many of her other films, a struggle for control between two men is at the forefront of this alternative family unit. Casting Harrison Ford as the often tyrannical Vostrikov is another example of Bigelow using an actor’s star status and past roles to play with the viewer’s expectations. Ford holds a strong place in the action genre, but he usually portrays the strong and adventurous all-American hero; Vostrikov is quite a departure from this persona. It seems that audiences were not comfortable with this departure, as many critics described Ford as being woefully miscast. Echoing Point Break’s Johnny and Bodhi and The Loveless’ Vance and Davis, Polenin and Vostrikov compete for command and power. Ultimately though, there is a mutual respect between the two men. Vostrikov becomes obsessed with control and a desire to gain party approval. He is the unrelenting father figure, while Polenin becomes almost maternal in the way he nurtures the crew and puts their needs before his own. These male power struggles continue throughout the film, with Polenin constantly urging Vostrikov to put the crew first. On one particular occasion, Vostrikov exclaims that he “took them to the edge because we needed to know where it was,” a sentiment reminiscent of Tyler’s description of Bodhi in Point Break, as well as Bigelow’s own preoccupation with blurring boundaries and pushing limits in her films. The crew ultimately does bond into a coherent family and they are forced to come together to fix the reactor, despite their lack of appropriate equipment. Vostrikov eventually grows as a father figure and puts the needs of his figurative children first, despite the consequences for the party. This is the typical plot of a melodrama, but Bigelow plays with the typical association with the ‘women’s picture.’ The scenes that surround the welding of the reactor illustrate the film’s overt melodramatic aspects, and the structuring of the shots only helps to highlight this.

Music is used overtly in this sequence, to the extent that it becomes somewhat self-reflexive, echoing the fact that early melodrama – literally meaning drama of music – used music as a means of increasing emotional response. Church bells ring as the men walk into the reactor, shot in slow motion. Operatic music begins to play and there are close-ups on their faces as the two men help each other with their masks, looking longingly into each other’s eyes. The music stops and there is silence as Vostrikov clicks the timer, at which point it swells back up. The beauty of an unlikely subject is reflected in the camera’s treatment of the reactor. The torch shoots flames as the music crescendos and the idea of men helping other men is almost elevated to the level of a spiritual experience. The idea of melodrama comes up again at the end of the film. Classical music plays as Vostrikov, Polenin and the other survivors toast the men who were lost, lamenting that they were not given the title of hero. The final moments depict the young men on an ice floe having their picture taken. The frame freezes, and the image slowly fades to black and white. There is nostalgia for the happiness and innocence of the past, a traditional trope of melodrama. Once again, Bigelow plays with expectations of gender and genre, using the conventions of the melodrama and the women’s picture to tell a story that is exclusively about male experiences.

While Bigelow’s seven feature films, made over the course of twenty five years, do not make her a prolific director by any means, they do allow viewers to see trends that occur across her body of work. Over the course of her career, Bigelow has experienced critical and commercial success, as well as failure. Only time will tell how her upcoming film about the Iraq War, The Hurt Locker (2008), will be received. Regardless of its reception, it is sure to embody issues that continue to be of concern for Bigelow such as genre, gender, alternative families and outsider groups. Bigelow continues to actively distance herself from being read as a distinctly female voice, finding such labels to be irrelevant. This idea of distancing extends to her films, as she continues to blur the borders between masculine and feminine, while also refusing to adhere to established conventions surrounding genre and traditional family values, as well as focusing on groups who exist outside of the dominant ideology. As Deborah Jermyn notes, “it is this difficulty in ascribing labels to her work that is, paradoxically, characteristic of a Bigelow film” (130). The definition of her work lies in its inability to be defined. In this respect, Bigelow’s films resist classification in much the same way that she attempts to as achieve with her public persona, wanting to be seen as just a director – not someone who is constantly characterized by her gender. She too is an outsider, a distinct blend of masculine and feminine that cannot be restricted to one particular style.

Works Cited

Brown, Jeffrey A. “Gender and the Action Heroine: Hardbodies and the Point of No Return.”Cinema Journal 35.3 (1996): 52-71.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Writing on the Body: Female Embodiment and Feminist Theory.Eds. Katie Conboy, Nadia Medina and Sarah Stanbury. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. 401-417.

Cook, Pam. Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Grant, Barry Keith. “Man’s Favorite Sport: The Action Films of Kathryn Bigelow.” Action and Adventure Cinema. Ed. Yvonne Tasker. New York: Routledge, 2004. 371-384.

Jermyn, Deborah. “Cherchez la femme: The Weight of Water and the Search for Bigelow in ‘a Bigelow’ film.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 125 – 144.

—. “Hollywood Transgressor: The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond.London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 1 – 20.

Lane, Christine. Feminist Hollywood Cinema: From Born in Flames to Point Break. Detroit Wayne State University Press, 2000. 99-124.

—. “From The Loveless to Point Break: Kathryn Bigelow’s Trajectory in Action.” Cinema Journal 37.4 (1998): 59-81.

—. “The Strange Days of Kathryn Bigelow and James Cameron.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 178-197.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Feminist Film Theory: A Reader. Ed. Sue Thornham. New York: New York University Press, 1999. 58-69.

Redmond, Sean. “All That is Male Melts into Air: Bigelow on the Edge of Point Break.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 106-125.

Self, Robert T. “Redressing the Law in Kathryn Bigelow’s Blue Steel.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 91-105.

Shaviro, Stephen. “Straight From the Cerebral Cortex: Vision and Affect in Strange Days.”The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 159-177.

Smith, Gavin. “Momentum and Design: Interview with Kathryn Bigelow.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 20-31.

Stilwell, Robynn J. “Breaking Sound Barriers: Bigelow’s Soundscapes from The Loveless to Blue Steel.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor. Eds. Deborah Jermyn and Sean Redmond. London: Wallflower Press, 2003. 32 – 57.

Tasker, Yvonne. “The Cinema as Experience: Kathryn Bigelow and the Cinema of Spectacle.” Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema. Ed. Yvonne Tasker. London: Routledge. 1993. 153-166.

Hi a most interesting essay on a topic I am currently studying myself for my third year dissertation, would very much like to talk further on the subject if you could find the time.

[…] Parenthood, gave Utah a boyish charm that related loosely to these two dimwitted characters on the “brink of manhood”. Yet like Willis’ McCane, Utah reflected shifts in perceptions of […]

Wonderful. I agree.

Excellent way of describing, and pleasant post to obtain information regarding my presentation topic, which i

am going to present in university.