Susan Ingram

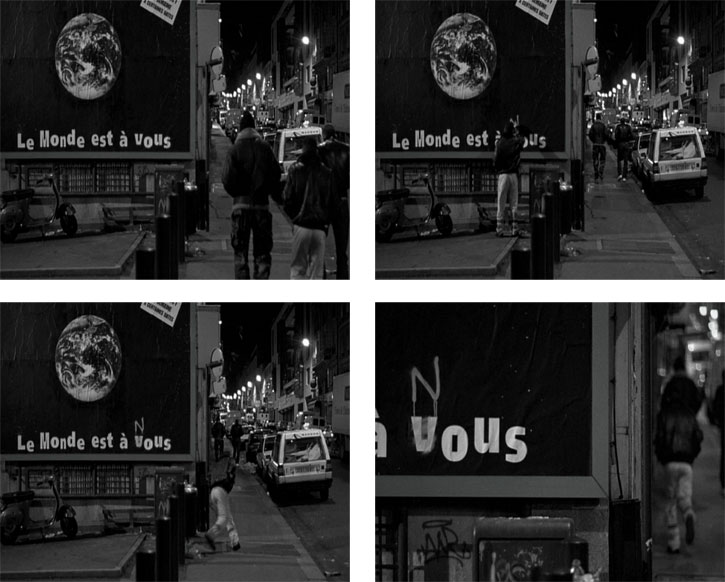

The premise of this piece is that what some still insist on calling the “revolution” of 1989 reverberated into a new type of film, in which anxieties caused by the new socio-political realities of the post-Soviet era were reflected in a new imaginary, literally a new vision, that is in an important way ‘European.’ Following Barry Langford’s processural understanding of genre, I am interested in the emergence, “the social” to speak with Gledhill, the “making” in the socio-historical, cultural and economic rather than film-making sense, of a distinct strand of cinema: grungy yet stylish, youth-oriented, urban films able to achieve more than a modicum of global popularity in no small part due to their protagonists, who are depicted as somehow managing to get ahead despite being positioned as part of the growing underclass needed to service new forms of the disorganized global finance capitalism theorized by John Urry and Scott Lash. Films like La femme Nikita (Luc Besson, 1990), Lola Rennt (Tom Tykwer, 1998) and Yamakasi (Ariel Zeitoun and Julien Seri, 2001) appeal to, and harness, creative and political energies by interfacing the urban and the global, which one could term the ‘gl-urban,’ echoing the ‘glocal’ terminology of globalization studies. This can be distinguished from the new impulses from different reconfigurations of revived realist traditions that European cinema received during the same period, which offer relatively straightforward social commentaries on difficult, often ethnic working and living conditions – for which La Haine (Mathieu Kassovitz, 1995) has become paradigmatic (see Mueller) – and also to be distinguished from the seductive, violent nihilism of films like Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) and Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996), which lack historical or utopian potential. Those who have made these films have recognized that they are in control of a key means of symbolic production, which, as Sharon Zukin explains in The Cultures of Cities, is increasingly the motor of urban economies. These filmmakers work against the aestheticization of diversity and fear by politicizing it in their films in a way that attributes agency to marginalized individuals rather than depicting them simply as ticking time bombs against which the mainstream needs to protect itself. As spaces and cultures understood as public in the sense of the journal Public Culture, “a forum for the discussion of the places and occasions where cultural, social, and political differences emerge as public phenomena” (http://www.publicculture.org/about, italics added), become increasingly corporatized and regulated, these spaces, their inhabitants and their histories are being reclaimed through representation in film. Zukin stresses that:

People with economic and political power have the greatest opportunity to shape public culture by controlling the building of the city’s public spaces in stone and concrete. Yet public space is inherently democratic. The question of who can occupy public space, and so define an image of the city, is open-ended. (11)

What Zukin leaves unstated is that this question is also open-ended because the image of the city is not only defined by those who occupy or build public space, but also by those who represent it. So while cities may increasingly be turning to culture to build up their economic bases in attempts to become ‘global’ or ‘world’ cities, it has been possible for some cultural producers to use some cities and the materiality of those cities’ histories and the histories of those who live in them to at least symbolically retake the streets, if not reverse the tendencies towards privatization, militarization and surveillance that we are increasingly forced to learn to live with. Cinema is thus not merely “an important factor in the social, political and cultural mutation of memory in the twentieth century, as analyzed by Pierre Nora and others in the early 1980s,… [taking] on the task of preserving and remembering, [and] indirectly institutionalizing forgetting” (Habib 124), one strand of it in particular has also been an equally important factor in the social, cultural and political reimagining of increasingly fragile public space.

Considering this type of film as an emerging genre, that is, naming and describing it as a cultural phenomenon, allows us to understand the appeal of a certain style of dislocated youth that have been depicted as coping with the socio-economic pressures subsumed in the term ‘globalization’ and to investigate the educational and political potential of these films, or, following Gayatri Spivak, to see how far they constitute “a program of the rearrangement of desires that education must assume” (10). The provisional answer I put forward here has to do with the re-imagining of European ‘public-ness’ Spivak invokes in referring to Europe as a “public concept” (2) in a complex narrative that contrasts but is imbricated in national forms of identification, which she identifies as more personal:

In your heart’s core you are Italian, you are English, American; in different ways. ‘Europe’ will still seem a public concept… The kind of statelessness that had moved Ursula Hirschmann to claim ‘Europe’ in the private core and sanctuary of her heart and thus to move out towards its public space, its public realization, has changed in the history of the last sixty years… now. The sense of being without a country is overcharged with an ontopological excess of country in the enclaves where gender festers in today’s ‘Europe.’ If, one might even say, you will not let me belong to your country you must build a simulacrum of the place where you and I both think I might belong, although, when I am there, I am ‘European’ now. (2)

My claim is that the films that belong to the emerging genre under discussion here reflect and offer a direction out of the ethnic and gender impasses Spivak evokes in this passage, impasses also evident in revived realist films such as La Haine but presented as intractable. As will be shown here, the concepts of cosmopolitanism and the lumpenproletariat can help to identify the specificities of a particular new type of film and locate the trajectory of the flight out it gestures towards. It is thus that I suggest designating these films as “Cosmotrash.” Cosmotrash refers to an alternative, post-1989 filmic imaginary of Europe, one which resists: 1) the ‘Eurocrat’ imaginary associated with the pragmatic, supranational yet regional priorities of the European Union; 2) the more traditional “high culture” imaginary associated with Old World coffee-houses, castles, Mozart, Beethoven, etc, and 3) national imaginaries for which trash, as Caryl Flinn points out, “has always been critical” (140). The pattern of these films detailed next will then be situated at the nexus of lumpens and cosmopolitans.

Protagonists in Cosmotrash films exist at an interesting crossroads: excluded from but necessary to the maintenance, smooth functioning and reproduction of the global capitalist status quo, they are able to find ways to beat the system at its own game, often literally. For example, in La femme Nikita, Luc Besson’s 1990 thriller about a young junkie “offered a new identity and the chance of relative freedom if she agrees to act as a highly trained government assassin” (DVD promotional material), the main protagonist is not a Cold War spy but rather an attractive young female drug-addict turned contract-killer for France’s foreign intelligence agency, DGSE. Trained to snipe away enemy targets in scenes that were to become the stuff of news reports from the Balkans in the mid-1990s, Nikita proves able to turn the new urban identity given her into a means of breaking away from the agency, with the help of a love-interest she literally runs into in the quintessential urban environment of a supermarket. In Yamakasi (Ariel Zeitoun and Julien Seri, 2001; co-written by Luc Besson), a gang of gymnastically-inclined, multicultural youth from the banlieue who specialize in free-running and sky-scraper-climbing, reach such cult status that schoolchildren start to emulate them. When one is injured doing Yamakasi moves and requires an organ transplant that the French medical system is unable to provide and the boy’s family is unable to afford, the gang is motivated to help. By breaking into the lavish homes of the directors of the private firm that brokers organs for the hospital, they are able to get the money that’s needed and thereby work to alleviate the racial and spatial divides in the city. Another film in which a city is virtually retaken in this manner is Wolfgang Becker’s 2003 hit Goodbye Lenin!, which literally draws concrete attention to a successful reimagining of the way the physical landscape of Berlin was corporatized after reunification. Unlike in more realist efforts, such as Nachtgestalten (Night Shapes, Andreas Dresen, 1999) and Berlin is in Germany (Hannes Stohr, 2001), the protagonist of Goodbye Lenin! is able to create a fantasy space, which allows his mother to recover from her coma and die a less traumatic death than doctors had predicted. A similarly successful retaking of Berlin occurs in Tom Tykwer’s Lola Rennt, when both Lola and Manni manage to get back the 100,000 marks Manni inadvertently leaves behind upon dashing out of the U-Bahn to escape ticket inspectors. They are thus able to walk away at the end of the film not only with Manni’s gangster-boss off their backs but also with money in the bag. In another likeably radical Berlin film, Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei (Hans Weingartner, 2004, distributed internationally under the clever English title The Edukators), the characters are idealistic young anarchists who break into mansions and villas in Berlin that are the equivalent to those the Yamakasi gang break into in Paris. They rearrange furniture and artwork, put statues in bathtubs, stereo equipment in fridges, leave messages saying “You have too much money,” and end up inadvertently but successfully kidnapping an industrialist when he arrives home unexpectedly. Finally, an English-language example: My Name is Modesty: A Modesty Blaise Adventure (Scott Spiegel, 2003) is an action film championed by Quentin Tarantino, which was shot in 18 days in Bucharest in 2002 so that Miramax could maintain rights to the source material (British author Peter O’Donnell’s popular novels and comic strips about cult-fave heroine Modesty Blaise). In this film, the eponymous heroine, a young refugee from the former Yugoslavia, breaks out of a refugee camp with Lob, ‘the Professor,’ a wise old man who once taught history in Zagreb, educates her in the literary and martial arts, and then is blown away when they are caught in mortar fire. Modesty is left to make her own way to Tangiers and conquer her own kingdom, a casino, which she eventually does, putting a lovely spin on the phrase “nights of the round table.”

All of these Cosmotrash films feature a cosmo-lumpen sensibility. Very hip, grungy-looking young adults are depicted not simply as drug addicts or two-bit hustlers, but rather as part of quasi-collectives with albeit partially-tenuous and disorganized agency that is able to do battle with the forces of disorganized global finance capital that, as Saskia Sassen likes to say, “hits the ground” in global cities. Cosmotrash films can be understood as an analysis of what happens when those forces hit what at the end of WWII was rubble, imbuing in the process the lumpenproletariat with politically cosmopolitan sensibilities.

Lumpenproletariat is the well-known Marxist term for the unproductive members of society: “this scum of depraved elements from all classes” as Engels called them in The Peasant War in Germany (Stallybrass 88); “the passively rotting mass thrown off by the lowest layers of old society” as they were described in The Communist Manifesto, while in the 18th Brumière they are “the dangerous class, the social scum,” “not just the lowest strata but… ‘the refuse of all classes'” (Stallybrass 85). Cosmopolitans have traditionally been understood as the opposite end of the spectrum: “men/citizens of the world.” According to Diogenes Laertius, the term cosmopolitan was coined by Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404-323 BCE), founder of the Cynic school, at the time of Alexander the Great. In response to a question about his origins, Diogenes reportedly claimed to be a kosmopolitis, a citizen of the world, who “refused to be defined by his local origins and group memberships…; instead, he defined himself in terms of more universal aspirations and concerns” (Nussbaum 6-7, cited in Ingram). Kant did much to modernize the concept, notably in his 1784 essay on the “Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View” and the 1795 “Perpetual Peace,” which contains the storied passage:

The peoples of the earth have entered in varying degrees into a universal community, and it is developed to the point where a violation of laws in one part of the world is felt everywhere. The idea of a cosmopolitan law is therefore not fantastic and overstrained; it is a necessary complement to the unwritten code of political and international law, transforming it into a universal law of humanity. (Kant 107-8)

This rational ideal is no longer of much use in helping us “to negotiate the transnational space that global capital [increasingly] produces,” which Ackbar Abbas sees as posing a critical question at the turn of our millennium: “Can there be a cosmopolitanism for the global age, and what would it be like?” (226). Yes, Abbas answers in “Cosmopolitan De-scriptions.” Befitting someone from a city enmeshed first by British imperialism and then by global finance, namely Asia’s “world city” Hong Kong, Abbas’s answer is “arbitrage with a difference,” playing with the distinction between arbiters (who see themselves as having the ultimate authority in a matter – the standard positioning of traditional Kantian cosmopolitans) and arbitrage, “the simultaneous buying and selling of securities, currency, or commodities in different markets or in derivative forms in order to take advantage of differing prices for the same asset.” Arbitrage with a difference, cultural arbitrage

does not mean the use of technologies to maximise profits in a global world but refers [rather] to everyday strategies for negotiating the disequilibria and dislocations that globalism has created. Arbitrage in this sense does not allude to the exploitation of small temporal differences but refers to the larger historical lessons that can be drawn from our experiences of the city…. [meaning that] the cosmopolitan today will include not only the privileged transnational, at home in different places and cultures, as an Olympian arbiter of value… [but] will have to include at least some of the less privileged men and women placed or displaced in the translational space of the city and who are trying to make sense of its spatial and temporal contradictions. (226)

In this sense, makers of Cosmotrash films can be understood as cultural arbitragers. They exploit as they add to the larger historical lessons that can be drawn from explicitly and specifically urban experiences.

However, there is more at stake in Cosmotrash film than cultural arbitrage. Triangulating cosmopolitanism with lumpenism and film is a way of deflecting the perennial universalism-relativism debate surrounding cosmopolitanism by literally grounding it within the gl-urban confines of particular representations of cities and thereby also ironically grounding the modern universal aspirations of the term in the free-floating post- or hypermodern space of global urbanity. Cosmotrash filmmakers are cosmopolitans with a difference, and the difference is not that they are among the less privileged who have been placed and displaced in the translational space of the city, although they do depict such characters in their films and do try to make sense of the resulting spatial and temporal contradictions. Theirs is also not “the diasporic, wandering, unresolved, cosmopolitan consciousness of someone who is both inside and outside his or her community” that Edward Said aligns at the end of Freud and the Non-European with Isaac Deutscher, the Jewish-British Marxist writer from Chrzanów in Galicia probably best known for his Trotsky and Stalin biographies (53). Unlike these other cosmopolitan consciousnesses, Cosmotrash films reveal one that has an ironically lumpen difference in that it abandons Marx and Engels’ proclivity for production. As Stallybrass lays out clearly, Marx and Engels used the lumpenproletariat in order to transvalue the term proletarian: “Whereas they found it [the term proletarian] as a mark of ‘a passively rotting mass’, they made it into a label of a collective agency. Moreover they inverted the meaning of the term, so that it meant not a parasite on the social body but the body upon which the rest of society was a parasite” (85). And they did so by offloading the fear and loathing that “passively rotting masses” generate onto the lumpenproletariat, which Marx resorted to foreign words to describe: roués, maquereaus (pimps), “what the French term la bohème”, literati, lazzarroni (“the lowest class in Naples living by odd jobs or begging,” Stallybrass 82-3). This all-too-familiar foreignizing, orientalizing impulse reflects a nineteenth-century valorization of and beholdenness to the ideal of productive action, which the lumpenproletarian disrupted in what was interpreted as their refusal to labor and to labor productively.

We find a similar refusal in the imaginary of Cosmotrash films, in which protagonists live alternative lifestyles and support themselves by non-traditional, often illegal (but never immoral) means. This refusal to labor is both European and public in Spivak’s sense, taking its cues from post-Soviet realities in which Europe has been made vulnerable by the incursion of global finance capital especially into newer E.U. member-states and attempting to raise not awareness or consciousness but rather hope about finding workable tactics in the face of overwhelming challenges. Understanding the precarious yet comraderly existences depicted in Cosmotrash films in terms of the relatedness of cinema, cities and intellectual history aims at ensuring that we will have “extricated ourselves from the modernist political imagination that is the legacy of people like Le Corbusier” (Donald 92). Much work still remains to be done in this regard, however. Trash is still all too often treated as a problem in and of itself, in need only of disposal, rather than as a sign of more deep-rooted structural problems which, if left unaddressed, only continue to generate more trash. Cosmotrash films try to make us aware that this process is precisely what feeds the global capitalist machine that tries to turn humanity’s most precious resource – its talented, highly able young people – into trash.

Works Cited

Abbas, Ackbar. “Cosmopolitan De-scriptions: Shanghai and Hong Kong.” Public Culture 12.3 (2000): 769-786.

Donald, James. Imagining the Modern City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Flinn, Caryl. “Somebody’s Garbage: Depictions of Turkish Residents in 1990s German Film.” The Cosmopolitan Screen: German Cinema and the Global Imaginary, 1945 to the Present. Eds. Stephan K. Schindler and Lutz Koepnick. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007. 140-58.

Gledhill, Christine. “Rethinking Genre.” Reinventing Film Studies. Eds. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. London: Arnold, 2000. 221-43.

Habib, André, “Ruin, Archive and the Time of Cinema: Peter Delpeut’s Lyrical Nitrate.” SubStance 35.2 (2006): 120-39.

Ingram, James. “Rethinking Cosmopolitanism: The Ethics and Politics of Universalism,” dissertation, New School of Social Research, 2007.

Langford, Barry. Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005.

Mueller, Gabrielle. “‘Welcome to Reality’. Constructions of German Identity in Lichter (Schmid, 2003) and Halbe Treppe (2002).” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 4 2 (2006): 117-27.

Said, Edward. Freud and the Non-European. London: Verso, 2004.

Sassen, Saskia. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. 2nd edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “What is Gender? Where is Europe? Walking with Balibar.” The Fifth Ursula Hirschmann Annual Lecture on Gender and Europe. Badia Fiseolana: European University Institute: 2006.

Stallybrass, Peter, “Marx and Heterogeneity: Thinking?the Lumpenproletariat.” Representations 31 (Summer 1990): 69-95.

Urry, John and Scott Lash. Economies of Signs and Space. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 1994.

Zukin, Sharon. The Cultures of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

The movie actually boetrehd me by seeming to give too much credit to the white characters on the civil rights issue. In that respect it was very hard for me to watch, I believe the storyline didn’t need a white heroine and let’s face it there were few white heroes in that time and place. I wanted to love the movie but I couldn’t get past reality.

[…] issue starts with Susan Ingram’s Cosmotrash: A New Genre for a New Europe, followed by a look at so-called ‘torture porn’ in Gorno: Violence, Shock and Comedy. […]