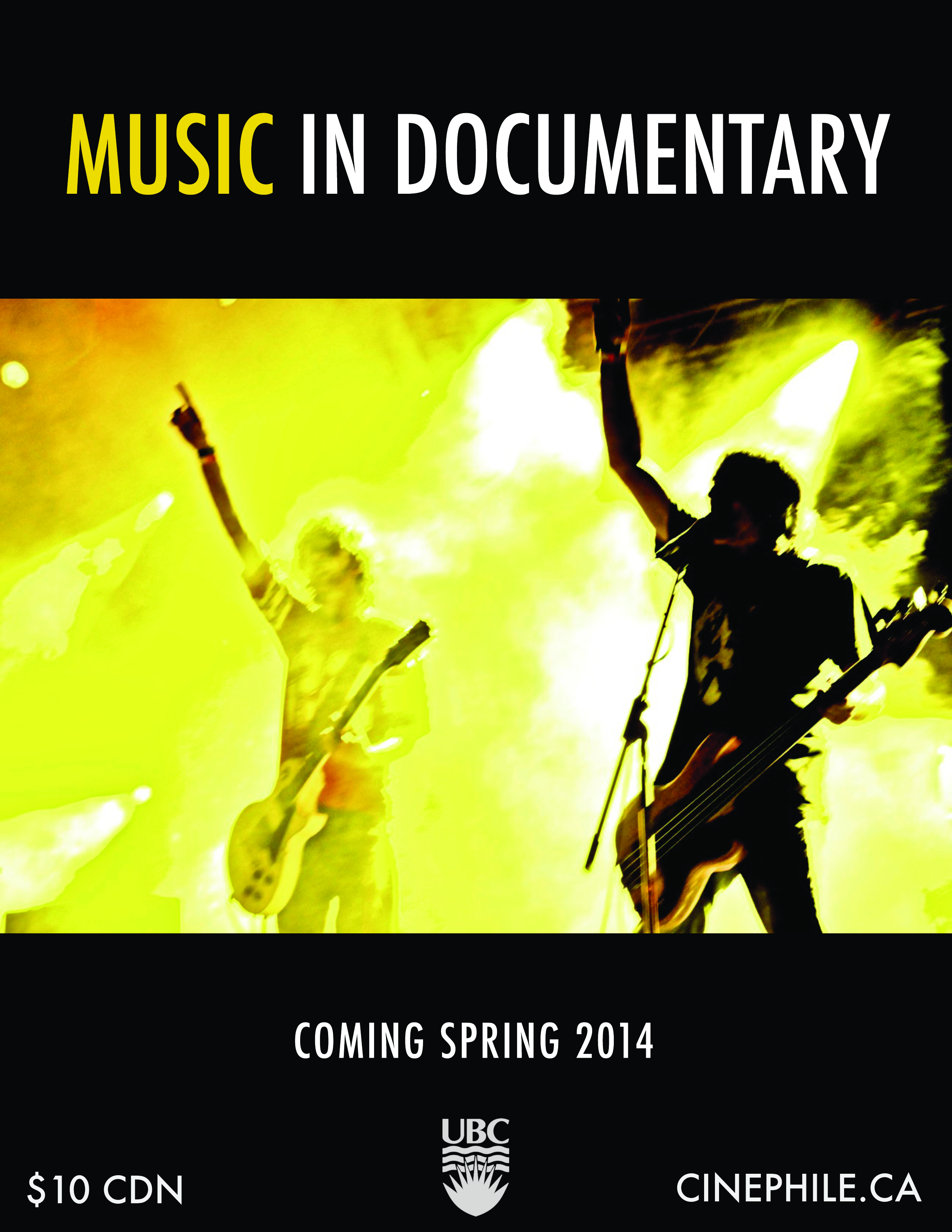

CFP – Music in Documentary (10.1)

Deadline for draft submissions: March 17, 2014

Music acts as vital connective tissue between even the most disparate forms of documentary, a filmic mode that claims closer ties to our experience of reality than any other type of filmmaking can. Although there has been a wealth of scholarship devoted to documentary’s technical innovations/limitations, its historical or sociopolitical contexts, and the visual treatment of the subject matter in question, the use of music in documentary films has been granted relatively scant attention.

Yet music can manifest in a myriad of forms in documentary filmmaking: it may appear as the explicit subject matter of a documentary, referring to the technicalities of musical production, performance, and the people responsible for that performance; it can be used as wallpaper that subtly colourizes the world of the documentary and guides the viewer’s emotions; or it can overtly manipulate the viewer’s opinions of the subject. Philip Glass’ minimalist scores in Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi trilogy (1982-2002) provide a forceful narrative push to what is largely considered non-narrative cinema, while the Maysles Brothers’ hand-held cameras and microphones offer sonic time capsules that capture the musical performances of the Rolling Stones in Gimme Shelter (1970) as they happened. Indeed, there is a vast body of documentary subgenres that can be sifted through in relation to this topic, such as the travel/nature documentary, the music/rock documentary, and the ethnographic film when considering the ramifications that the use of music may have upon both the viewer and the subject. In addition, there is an equally ample collection of modes within the documentary tradition that have been famously defined by scholar Bill Nichols and which include the observational, poetic, or performative mode, to name but a few.

In the interest of fostering a celebration of the inherent differences between the many documentary subgenres and modes that exist, Issue 10.1 of Cinephile will explore how music can both cultivate these creative differences and open up categories to wider discursive scrutiny. We look forward to receiving submissions about documentary films from all historical periods and nations, in hopes of harbouring a site where a range of scholarly interests devoted to the underdeveloped study of music in documentary may converge.

Starting points might include:

– Relationships between the audience’s live experience of a musical event and its mediated form

– Questions of authenticity as they manifest in sound or performance – is live music as authentic as mediated music?

– Explorations of documentary’s manipulation/stylization of music as can be compared/contrasted to fiction film’s use of music

– How docufiction, essayistic films, and/or mockumentaries incorporate music in a way that plays off of commonly used documentary techniques

– Music’s relationship to larger industrial or commercial trends – how can documentary music be used as a selling point? How have artist-controlled digital distribution methods, Web 2.0 interfaces, and mass media impacted synergetic practices?

– How gender representation and queer theory engage with a documentary’s music and performances

– Music’s cultural or transcultural connotations – how does music appear/sound across nations in documentary, how is music used to reflect or challenge notions of national identity?

– Phenomenological approaches that take into account the affective properties of music, and how they might deepen our experience of a documentary at a haptic, kinesthetic, or synesthetic level

– An auteurist angle – in regards to filmmakers, composers, sound technicians/designers, and/or music supervisors across an oeuvre of documentary works

– Musicological analysis of a film’s diegetic and/or non-diegetic music; how these two strains of music interrelate/intersect/diverge in one or multiple films

– Cross-textual examination of documentaries that have been re-scored (i.e. Man With a Movie Camera)

We encourage submissions from MA and PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, and faculty. Papers should be between 2000-3500 words, follow MLA guidelines, and include a detailed works cited page, a short biography of the author as well as a brief 300-word abstract.

Submissions and inquiries should be directed to: cinephilesubmissions@gmail.com

Cinephile is the University of British Columbia’s film journal, published with the continued support of the Centre for Cinema Studies. Previous issues have featured original essays by such noted scholars as Sarah Kozloff, K.J. Donnelly, Barry Keith Grant, Matt Hills, Ivone Margulies, Murray Pomerance, Paul Wells, and Slavoj Žižek. Since 2009, the journal has adopted a blind peer-review process and has moved to biannual publication. It is available both online and in print via subscription.

[…] Zoë Druick and Gerda Cammaer (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014), the forthcoming issue of Cinephile (10.1), and on the Sounding Out! blog. And my postdoc work is now forming the basis for the […]